When did Taliesin get its front door?

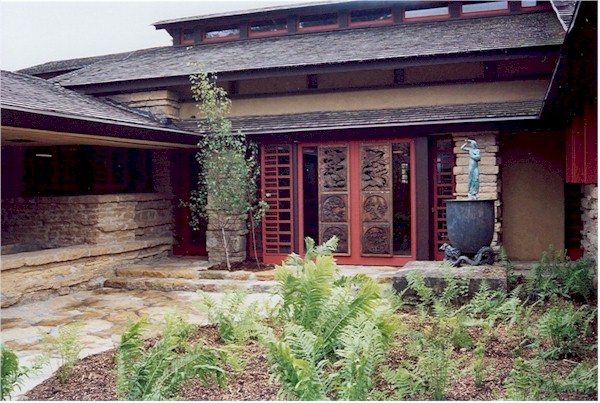

My May 2004 photograph looking at Taliesin’s entry and entry foyer.

I find humor regarding Wright’s placement of his own home’s front door, so my post today is going to be about that.

I say “humor” because of how Wright is praised on his placement of the front doors of his homes. That he placed the entrances in ways that create a journey of surprise to visitors as they seek them out.

Therefore, his houses do not usually have the front doors smack dab in front of you.

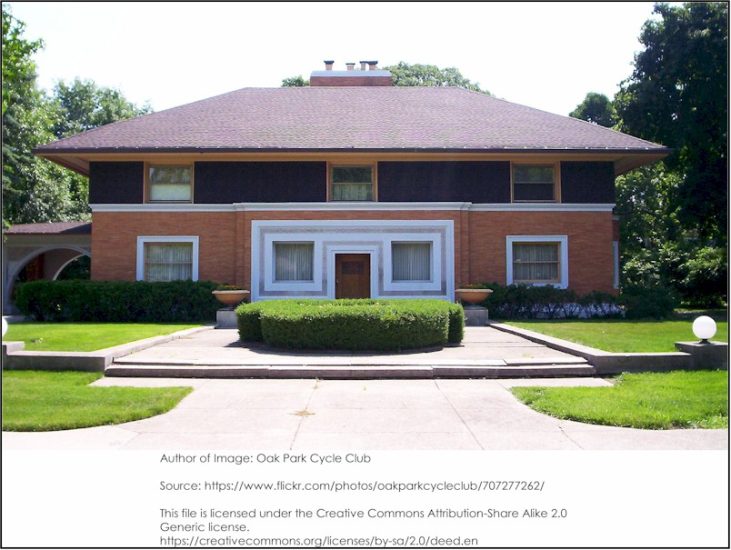

Ok, well there was that one time.

And he was young! The house (the Winslow) was his first independent commission in 1893. He was 25 or 26. Haven’t we all done things as we’re learning the ins and outs of our own lives?

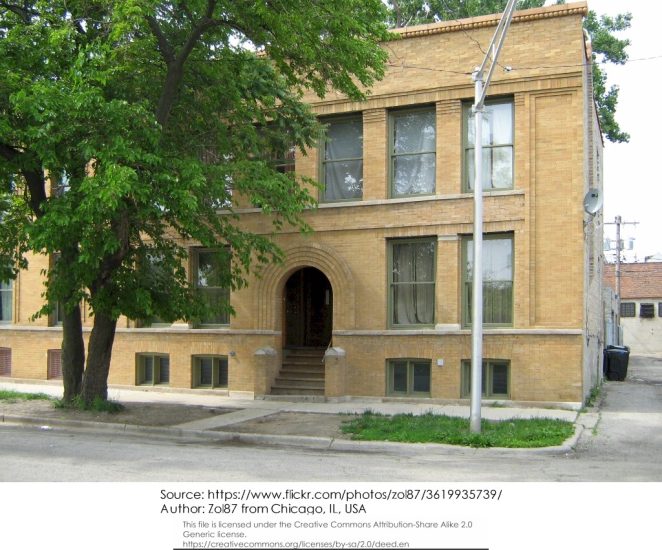

Well, THAT’S an apartment building. You gotta make the entry really large to help people to go in —

STOP THAT!!

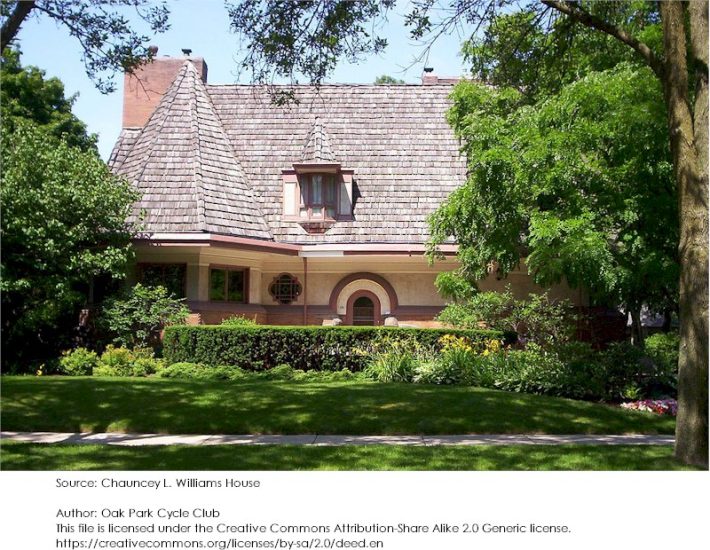

Those are all photographs of Wright buildings, but I’m trying to make a point.

. . . . Against my fictional self.

But, seriously: I find the history of Taliesin’s “front door” funny because, when he first designed his home in 1911, when you arrived at Taliesin’s first courtyard, a door was one of the first things you saw, but it wasn’t the front door.

Let me back up and show you:

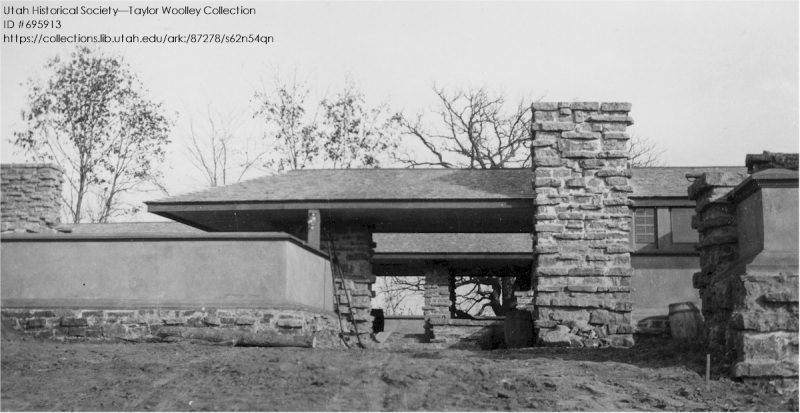

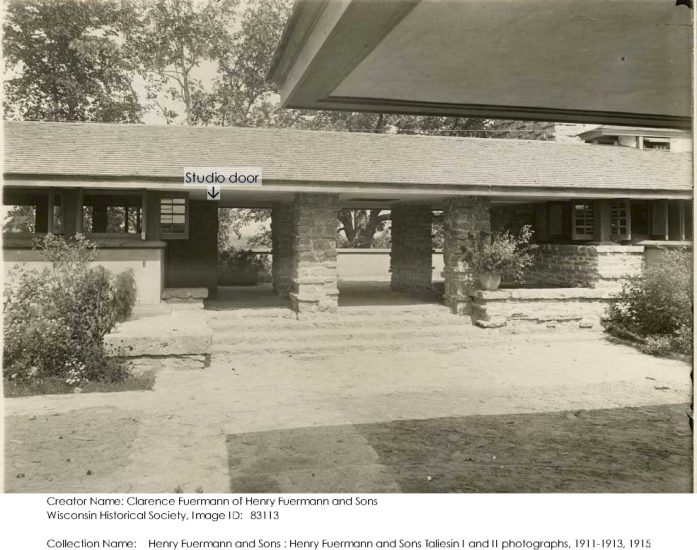

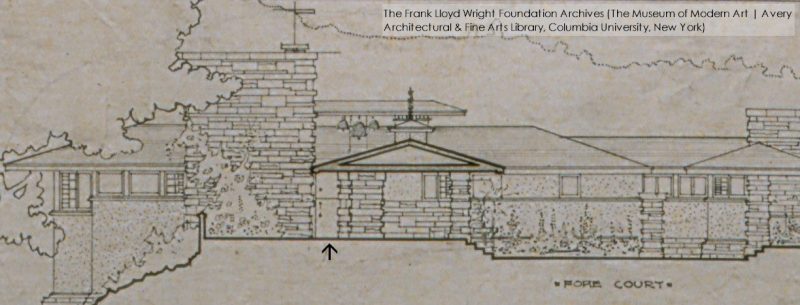

So, in 1911, you would drive past Taliesin’s waterfall, and along the carriage path up the hill, and stop under the roof of the Porte-Cochere, in the photo below.1

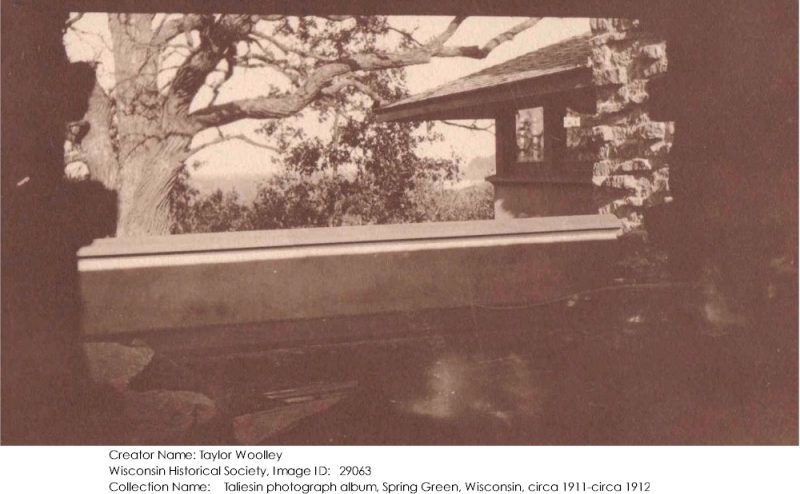

This photograph was taken by Wright’s draftsman, Taylor Woolley, in the late fall or early spring, 1911-12.

And once you stopped under the roof, you could get out of your vehicle and walk into the “forecourt”. And here, you saw this door, behind the vertical wood strips there at the low wall near the middle of the photo:

And yes, behind the vertical pieces of wood are bug screens. Even though Wright supposedly hated them. I think it took only one summer in Wisconsin, with the Taliesin pond, for Wright to understand that the mosquitoes in Wisconsin can be pretty nasty.

Knowing me, if I were invited to Taliesin in 1912 I probably would have walked right up to that door, figuring that was the main house entry. But that’s not where Wright designated the front door. No; apparently Wright’s planned trip for visitors to the main, formal, Taliesin entry was that they would walk straight from the Porte-Cochere, through the forecourt, and up three steps and under the roof on the left that you see in the photo above.

The photo below I think shows you the straight shot he wanted you to take.

The continued walk to the door:

You go up those steps and under that roof. And on your left was another door. Which was not the front door.

Here’s why I think this is funny: in many of his designs, I get the impression that there is just one door that he intentionally leads you to. But at his home, he’s got these other doors and I think I’d get frustrated after awhile.

Although under the roof, you could see the river

I think he hoped to draw you to the view in the distance to see the Wisconsin River.

And, then you’d see the front door. It would be on your right.

The best view of the door is actually in a drawing:

I’ve never seen a photo of that door on the outside during Taliesin I or II.

You can only see the door at that time from the inside, at Taliesin’s living room. You can see one view on the other side of the inglenook which I wrote about in my last post, 1940s Change in Taliesin’s Living Room.

But the other thing that is really interesting was that when you walked through Taliesin’s “front door” at that time, you walked right into the Living/Dining room of Taliesin.

And before that, you walked passed the kitchen.

This caught my eye starting about three months ago:

That’s because I was writing an article on Wright’s kitchens at Taliesin. This will appear in the Spring 2022 edition of the magazine, SaveWright . SaveWright is the magazine put out by The Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy.

Here’s one thing Wright wrote about kitchens in 1907:

… Access to the stairs from the kitchen is sufficiently private at all times, and the front door may be easily reached from the kitchen without passing through the living room.

“The Fireproof House for $5,000”, in Frank Lloyd Wright Collected Writings: 1894-1930, volume 1. Edited by Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, introduction by Kenneth Frampton (Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., New York City, 1992), 81-2.

So, he’s not paying attention to this, in his own home. At that time at Taliesin, the only way to get to the front door would be by walking past the kitchen. And, if you were inside the kitchen, the only way to get to that front door would be by going through the living room/dining area.

You’ll see this if you look at the Taliesin drawing in my post, “Did Taliesin Have Outhouses?“

And he’s working out these ideas at Taliesin: like I wrote, “The Fireproof House for $5,000” was published in 1907.

In addition,

He does the same thing in Taliesin II

That is, 1914-1925

Although I think by that time, he tried to hide that first door when you stopped at the Porte-Cochere.

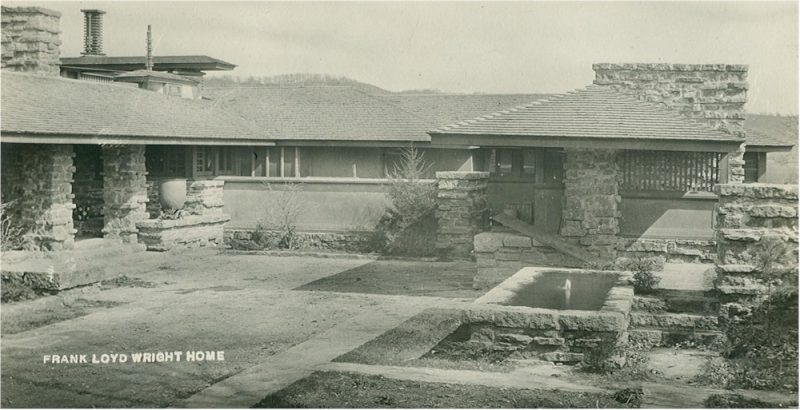

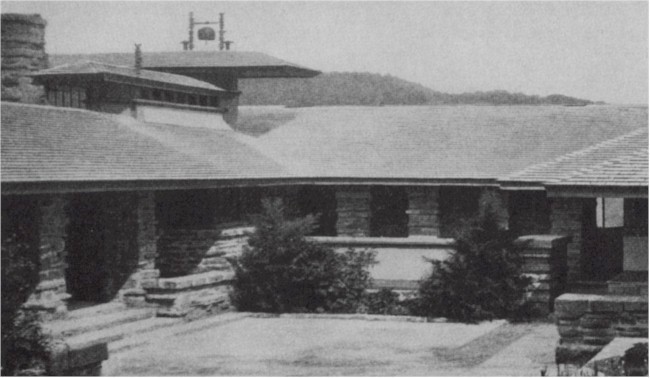

Here are a couple of Taliesin II photos:

Collection Name: Henry Fuermann and Sons Taliesin I and II photographs, 1911-1913, 1915

Collection Name: Henry Fuermann and Sons Taliesin I and II photographs, 1911-1913, 1915

Taliesin’s front door is past the ceramic vase you see in the shadows. The kitchen is through the open windows that you can see above the low, stucco, wall.

Then the 1925 fire happens

So, Wright keeps the door in the same place, but changes how you get there. And, for almost 15 years, he had you drive east of the living quarters to get arrive at the front door. An aerial photograph showing the road is below:

From the book, The Fellowship: The Unknown Story of Frank Lloyd Wright & the Taliesin Fellowship, by Roger Friedland and Harold Zellman (Harper Collins Publishers, New York, 2006). This image was published in the page opposite page 1.

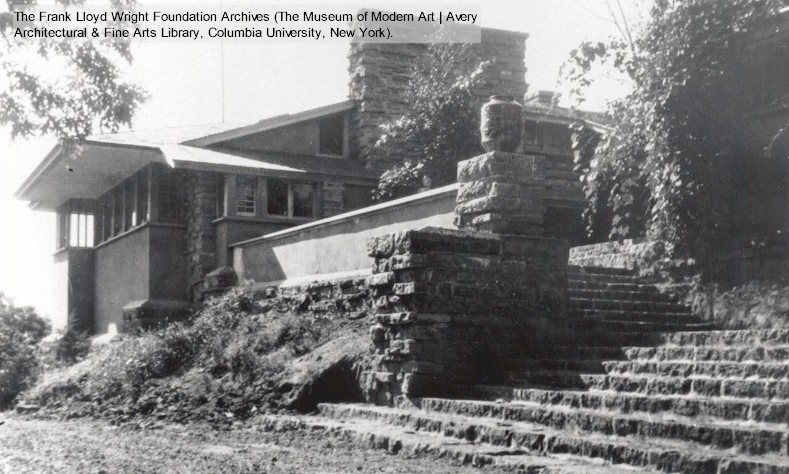

That road in the aerial brought you to the steps on the way to the front door that you see below in this 1929 photograph.

These steps took (and take) you to Taliesin’s entry. When this photograph was taken, you would walk up the three sets of steps and the door into Taliesin was to the right of the chimney.

Here’s what former apprentice Edgar Tafel wrote about his first experience walking into the house:

At Taliesin, we went through a Dutch door, its top half swinging open. Below, flagstone, and all around us natural stone. The ceiling was low, sandy plaster just above our heads. Wright led the way into his living room. What an impression that room made! It was my first total Frank Lloyd Wright atmosphere. How I was struck by those forms, shapes, materials! It was heartbreaking – I had never imagined such beauty and harmony.

This comes from page 20 in Apprentice to Genius: Years With Frank Lloyd Wright, the book I recommended last year.

In 1943, Wright changed the entrance to where it is now:

Another former apprentice, Curtis Besinger, wrote about his in the book, Working With Mr. Wright: What It was Like.

I mentioned this book when I wrote about books by apprentices.

He described in in the chapter, “Spring and Summer, 1943”:

It seemed that some students from Harvard had complained to Mr. Wright when visiting Taliesin that they had had difficulty finding the entrance. He was going to correct this.

… These new doors were visually on the center of the garden court, and made a stronger connection between the interior of the entry area and the court.

Curtis Besinger. Working with Mr. Wright: What it was Like (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, 1995), 147.

Re: “students from Harvard”:

When I gave tours, if I had time after bringing people to the front door, I’d tell them about the Harvard students. I often added that “Wright said Harvard took good plums and turned them into prunes.”3

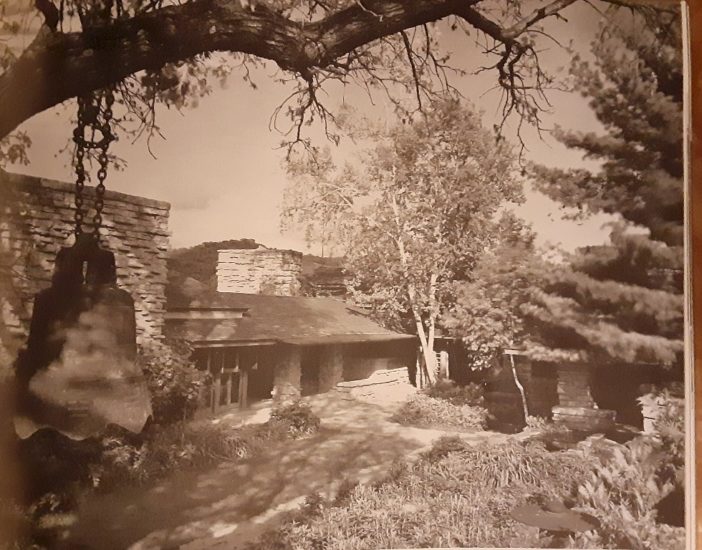

Here’s a photograph taken in 1945 (I included it in my post, “In Return for the Use of the Tractor“):

The formal entry was to the right of the two tall birch trees in the center of the photo. Although people usually went inside through the door to the left of the two tall birch trees.

Although the students from Harvard possibly influenced Wright to take away some of the FIVE DOORS that he had on that side of the house. Seriously: take a look at drawing 2501.048. It shows Taliesin’s living quarters, 1937-43.

First published March 26, 2022.

Notes:

- Another word I’ve learned while working at Taliesin. Porte-Cochere: a “carriage porch” and “a covered carriage or automobile entryway leading to a courtyard.”

The Dictionary of Architecture and Construction, 4th ed. (2006, Cyril J. Harris, ed., McGraw Hill, New York, 1975). - If you click on the drawing, you’ll see it’s characterized as “Taliesin II”. That’s wrong. Architectural details in the drawing show that this was actually 1911-14, Taliesin I. It just hasn’t been corrected. If you know anyone close to the Avery library who wants to contract with me as a consultant to correct these dates on Taliesin drawings, I’m all up for it; please give them my contact information. Thx.

- As always, I learned the “gist” of that quote, but I can’t find the actual quote itself.

Wright wrote something about the same in his book about mentor Louis Sullivan, Genius and the Mobocracy. Wright while writing about university education, says that the “creeping paralysis” in ” higher learning” takes “Perfectly good fresh young lives—like perfectly good plums… destined to be perfectly good prunes.”

That’s in the Frank Lloyd Wright: Collected Writings 1939-49, volume 4, 343-344.

I like the way I first heard it, rather than how Wright wrote it. Maybe he said it someplace else.