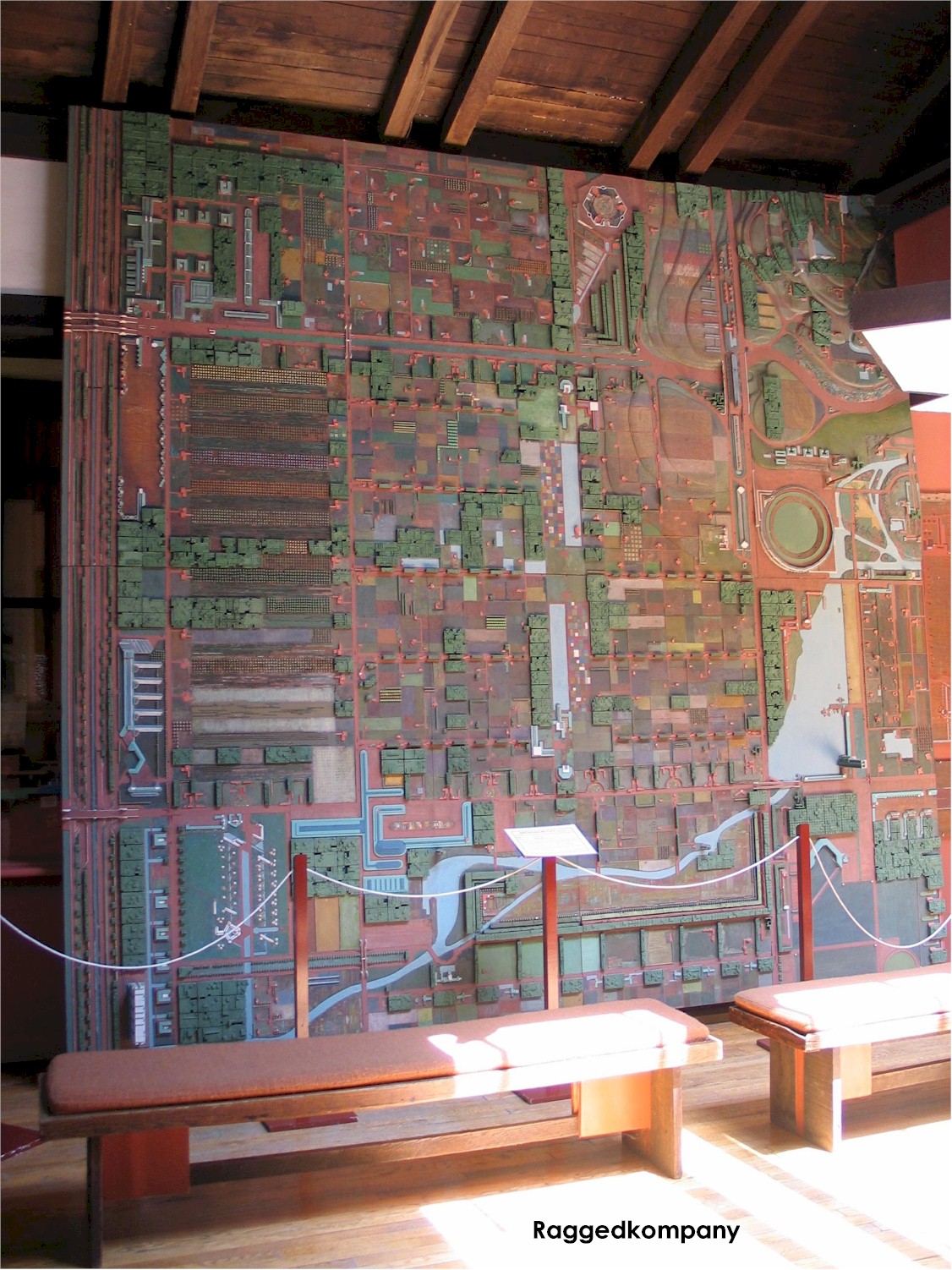

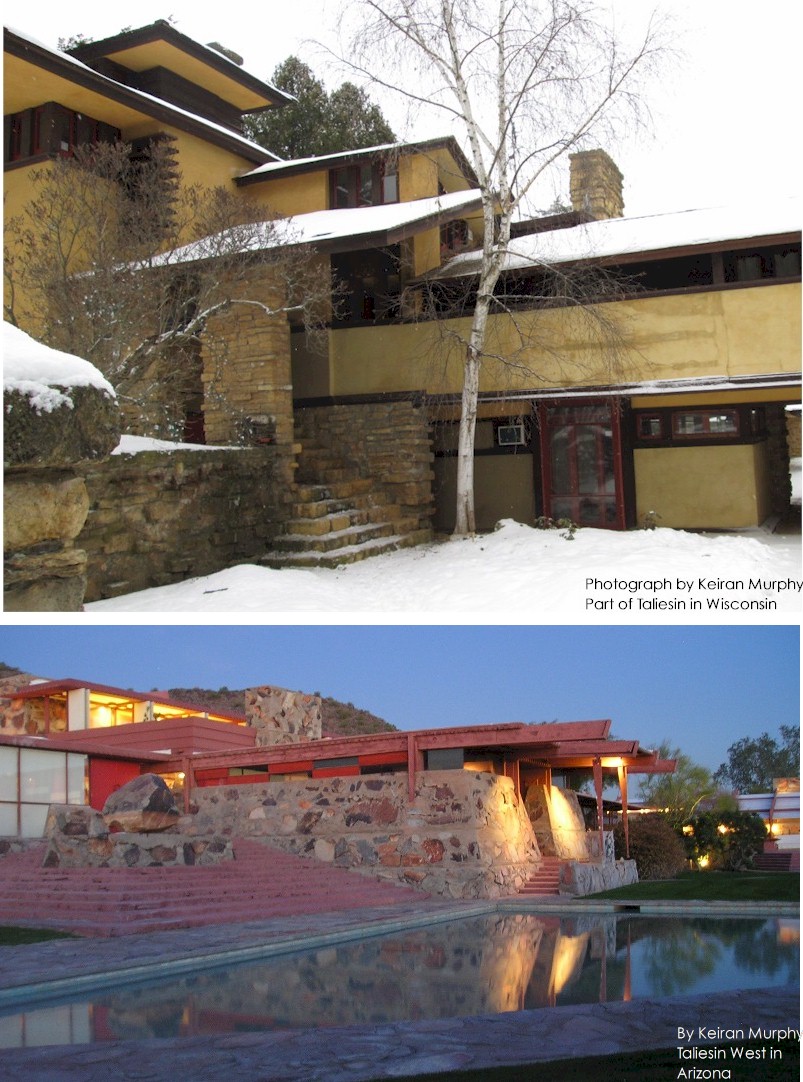

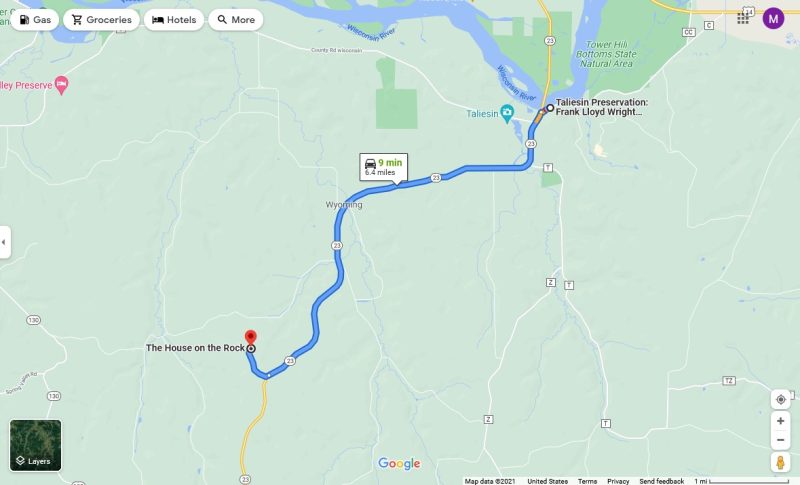

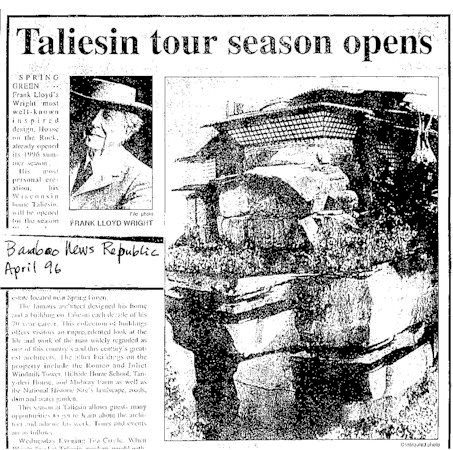

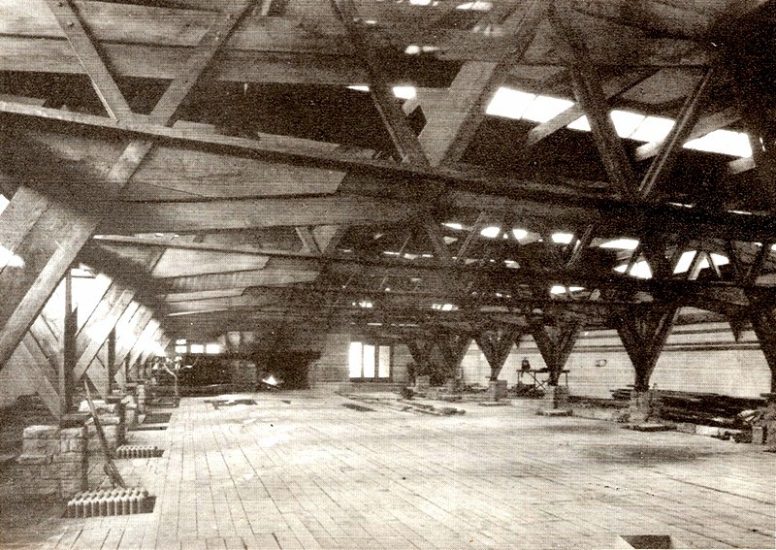

The model of Broadacre City, Wright’s idea/design for decentralized living. Photo taken while the model—mentioned in the post below—was once displayed against the north wall of the Dana Gallery at the Hillside building on the Taliesin estate. Raggedkompany took this photograph in 2008/09.1

One day over 16 years ago, a woman came in for a tour of Taliesin.

She did a kind and thoughtful thing

She brought photocopies of letters that her aunt, Lucretia Nelson, had written to her parents (this woman’s grandparents) while Nelson was in Wright’s Taliesin Fellowship in 1934. So this woman wanted to give this to someone associated with Taliesin.

Fortunately I was on hand to take these from her.

Her act caused me to name this post, “Preservation by distribution”. That is: you try to get copies of things out there, in order to help them survive.

I spoke briefly to Lucretia’s niece (Lois) before she took her tour of Taliesin. While she was on tour, I read her aunt’s letters as quickly as possible, while getting what info I could on Lucretia Nelson. It turns out that in 1934, Nelson had written an article for “At Taliesin”. These were weekly newspaper articles that the Taliesin Fellowship had written in the 1930s. So I copied that for her and had it when she came off the bus after her tour.

Architect and writer, Randolph C. Henning, collected, transcribed and edited these columns, which he put into a book. I wrote about this book in my post on books by apprentices.

That day I got Lois’s address, since I wanted to absorb some of what Lucretia Nelson had written. I felt I should give her more information once I had a some time to look things over. So when I did, I told her who Lucretia had mentioned, and pointed out an important event in Wright’s career that Nelson had written about.

I’ll talk about that further below. First of all, I should mention Lucretia and some of those people. And why she was at Taliesin.

Who was Lucretia Nelson?

Nelson (1912-1991) received a B.A. in painting at University of California-Berkeley in 1934. Apparently after graduation, she came into the Fellowship with a college friend, Sim “Bruce” Richards. Frank Lloyd Wright had seen Bruce’s work in Berkeley during a lecture and had encouraged the young man to join the Fellowship. So the two friends (Bruce and Lucretia) headed to Taliesin, where they met up with another former UC-Berkeley student, Blaine Drake (Drake had entered the Fellowship the December before).2

Lucretia was there in 1934, possibly into 1935. The men, who later became architects, stayed longer. Bruce until 1936; and Blaine until 1941. Meanwhile, Lucretia returned to UC-Berkeley, received a Master’s degree, then taught in its department of decorative arts, where she also became an administrator.

Her year in the Taliesin Fellowship was something that she often remembered and one can understand why: she was devoted to the connection between life and art, which she saw around her when in the Taliesin Fellowship.

Two things that stuck out in Lucretia’s letters:

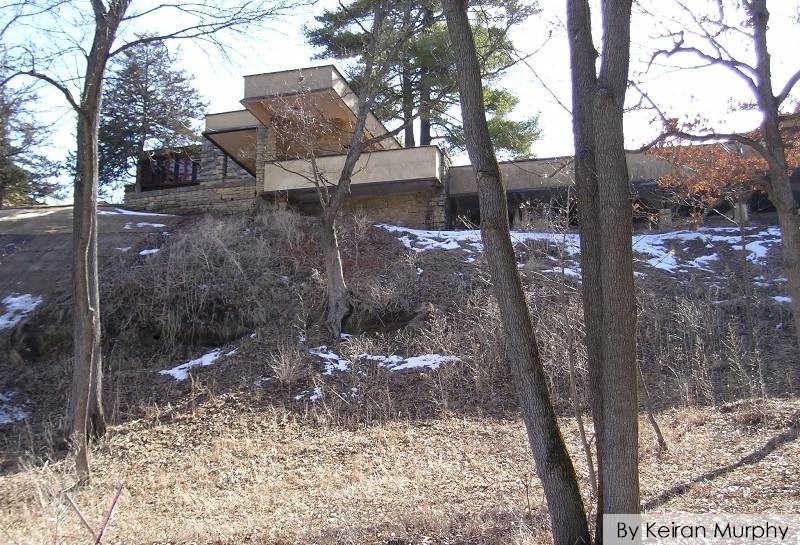

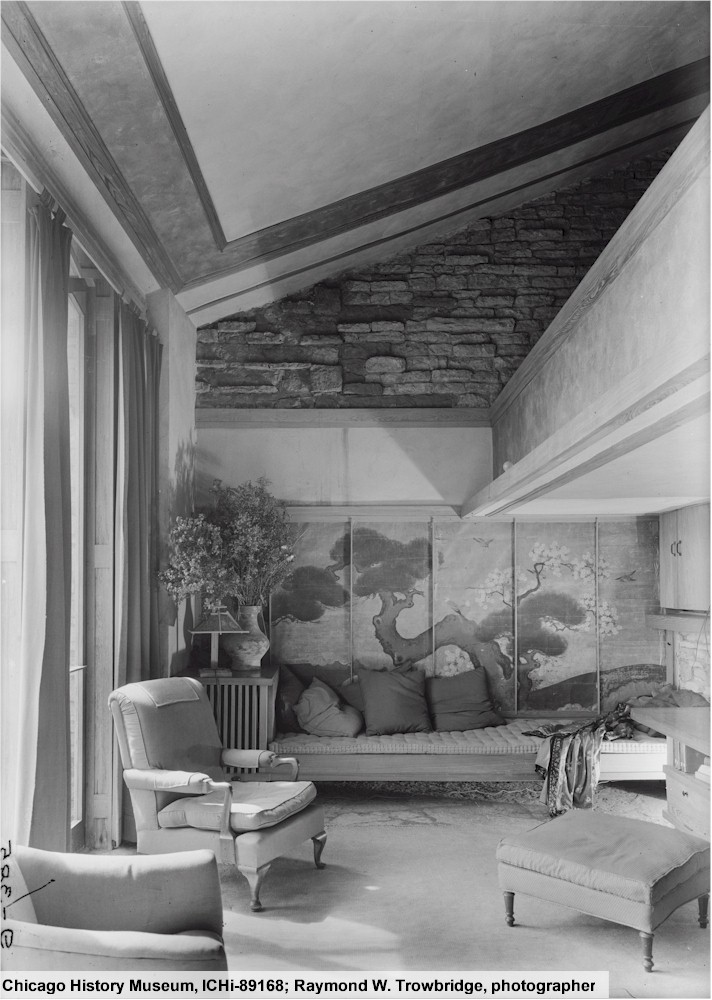

She wrote about one change to Taliesin. It was planned for her room, and she told her parents that:

“You see it gives me instead of one small window on the north side under the deep eves [sic]… a south exposure and a wall almost entirely of windows.”*

This change is going to cause a problem.

The upcoming change altered the room. The southern wall in the room was moved further south. The that was the wall that she said would be “almost entirely of windows”. Then-apprentice, Edgar Tafel, wrote about this change for the July 4th, 1935 “At Taliesin”. He said that,

Fortunately, Taliesin is in an ever state of change. Walls are being extended and new floors are being laid to accommodate our musical friends. We are trying out the new concrete mixer – which marks a new day in our building activities.

Randolph C. Henning, ed. and with commentary. At Taliesin: Newspaper Columns by Frank Lloyd Wright and the Taliesin Fellowship, 1934-1937 (Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale and Edwardsville, Illinois, 1991), 139-40.

This concrete caused a problem decades later:

Unfortunately for Taliesin, this concrete work blocked a drain behind this south wall. Water going behind the wall would freeze in the winter. This created a wedge from 1935 until the early 1990s. My understanding is that the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation (the site owners) began trying to figure out this problem in the late 1980s.

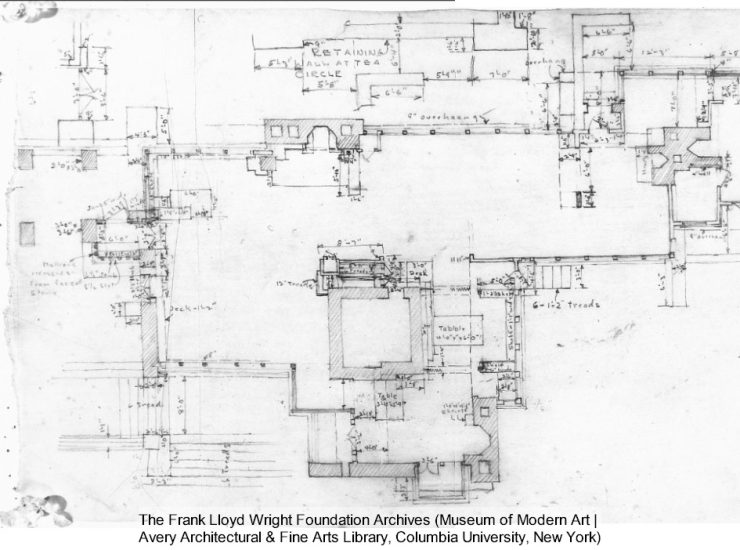

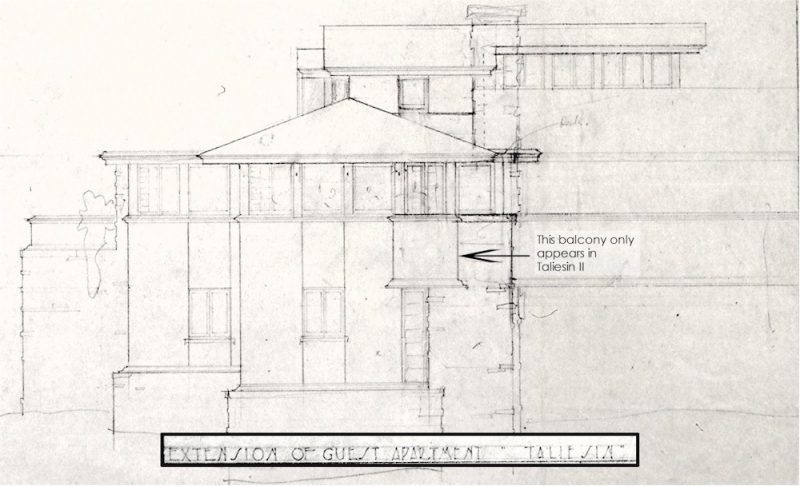

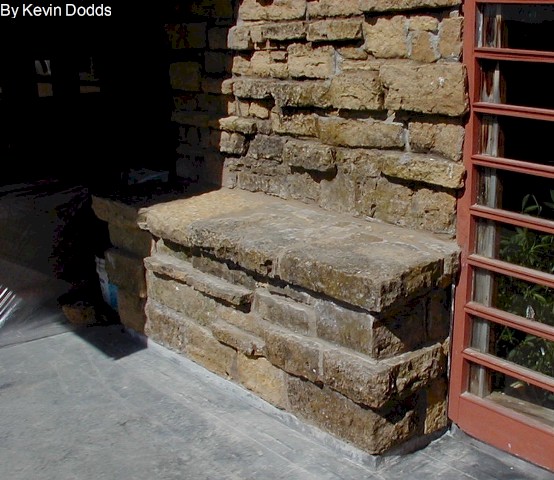

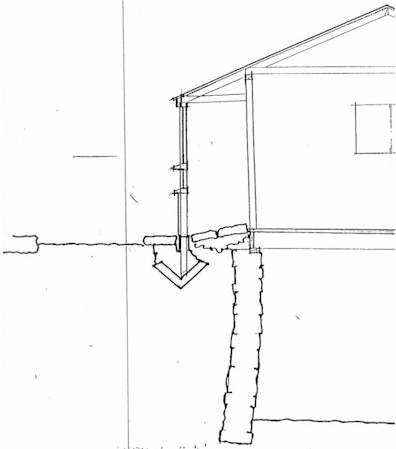

By that time, the back wall (visible on tours of Taliesin) was protruding seven inches out of plumb. Here’s a drawing that Taliesin Preservation did before the start of the project, just to give you a sense of things:

The part people saw was to the right of the stone wall.

During the preservation work, earth was removed from the back of the wall, which was slowly pushed back into place using jacks. This made the wall once again plumb. Then two drainage systems (one behind the wall) were installed.

This big project was done the winter of 1993-94; so it was the brand new project the year I started giving tours at Taliesin.

Lucretia’s other important note:

In that same letter where she mentioned the upcoming work, Lucretia said that “a guest last week” who “has his son here” gave $1,000 for the construction of Wright’s “Broadacre City” model.

Every Frankophile (in other words, a Wrightfan) in the audience might have done a double-take at that last sentence.

The model of Broadacre City was Wright’s thought project about decentralized living (not tied to any real site). This $1,000 gave Wright and the Taliesin Fellowship the resources to construct it.

And the guest was Edgar Kaufmann, Sr.

Who was Kaufmann?

Edgar Kaufmann, Sr. was visiting Taliesin (with his wife, Liliane), because their son, Edgar, Jr., had joined the Fellowship a couple of months before. Edgar Sr. ran Kaufmann’s, a department store in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Most importantly, in less than a year, he and Liliane would receive plans for their weekend home near Pittsburgh. That home is known as Fallingwater.

Fallingwater: the building that started to put Wright back on the forefront of architecture.

Kaufmann’s $1,000 check not only meant that the architect had the money so his apprentices could build the 12 foot X 12 foot model. The money seemed to signal that Kaufmann believed in Wright’s ideas and work. And that, perhaps, he might hire Wright for that home they were thinking of building.

Originally published, November 21, 2021.

Thanks to Raggedkompany for permission to use his photograph at the top of this post.

* I changed this post on May 7, 2020 when I realized I’d incorrectly identified a photograph. I deleted the photograph here, but talked about what room it was really showing in my post “Oh my Frank – I was wrong“.

There’s an earlier version of “Preservation by Distribution”, with the mistake. It’s on the Wayback Machine, here.

**Bonus—See my post about the glorious Wayback Machine, here.

1 In 2012 the model became part of the collection of The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (Museum of Modern Art | The Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York).

2 In case you’re wondering: as far as I know, Lucretia was just friends with both Bruce and Blaine.