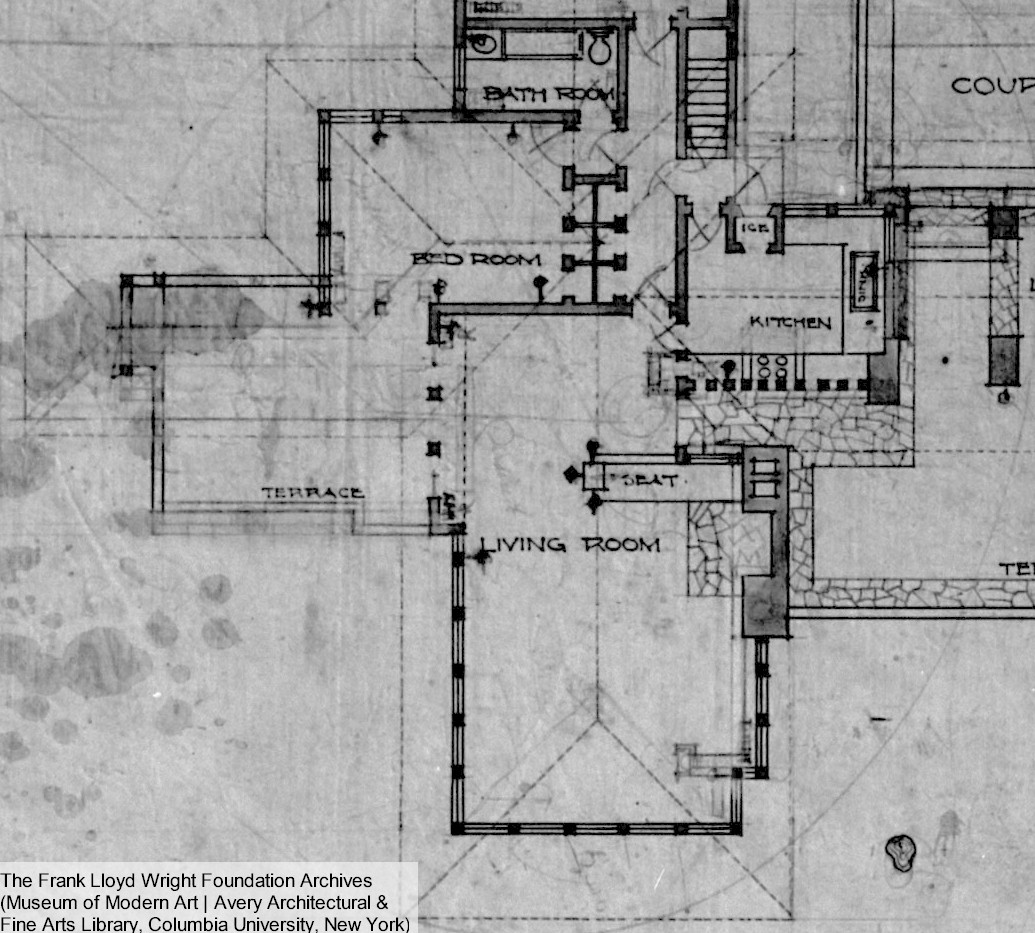

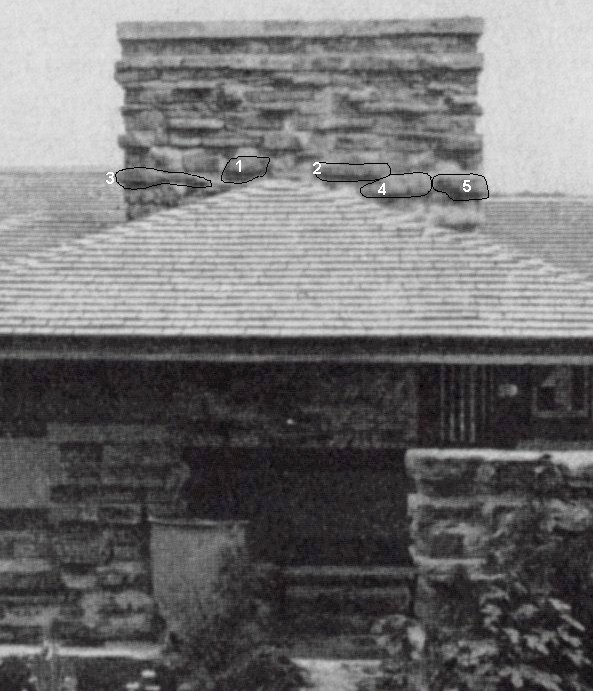

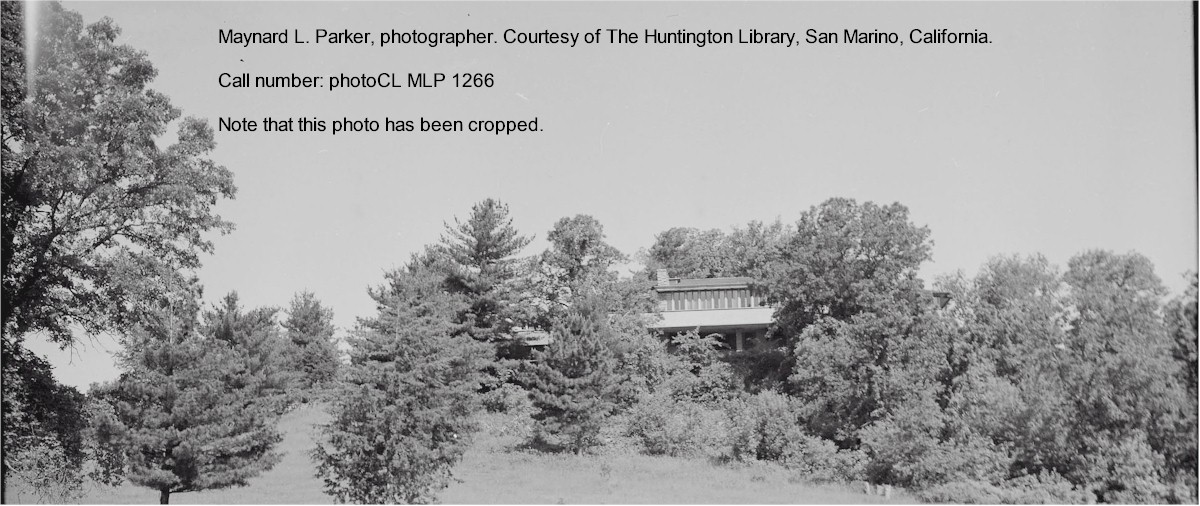

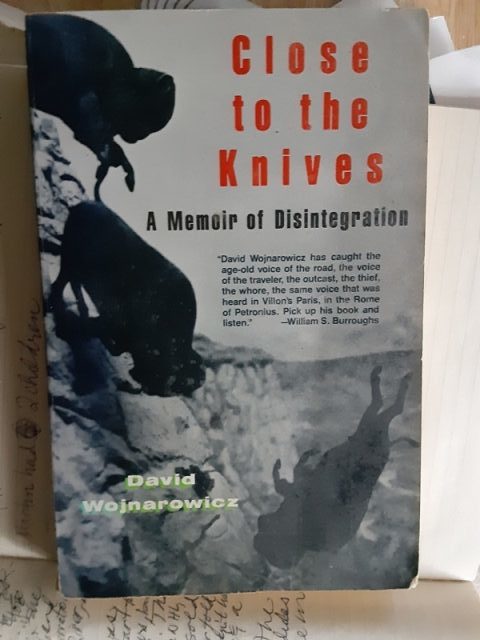

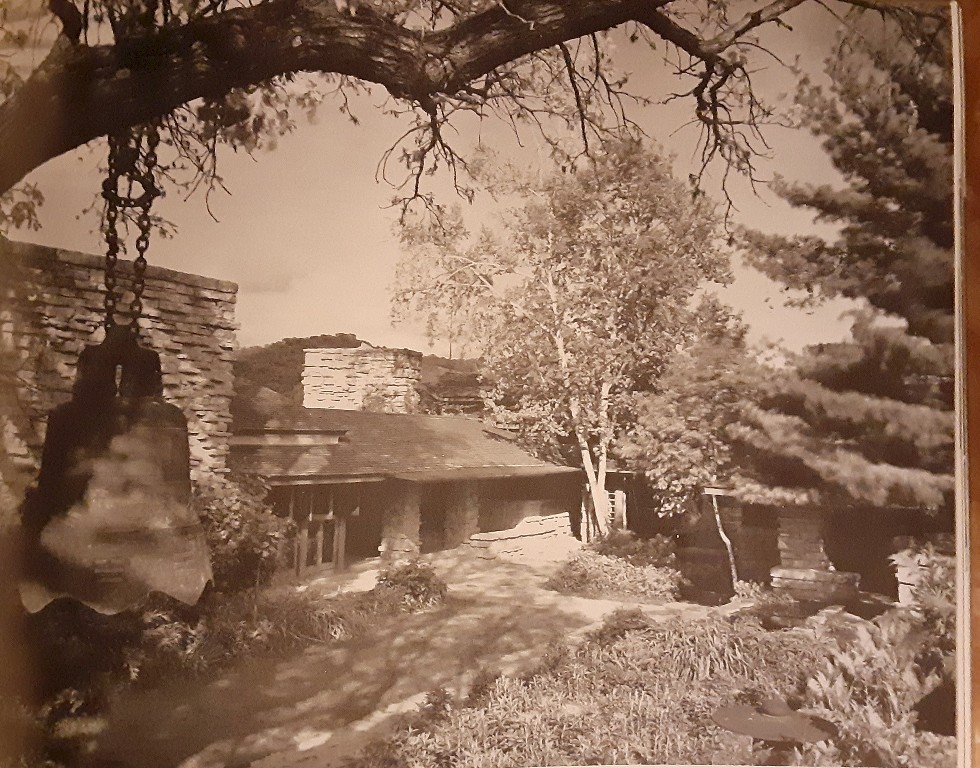

This photograph is looking from the Unity Chapel cemetery, which is the private cemetery of the Lloyd Jones family. Frank Lloyd Wright received permission to bury Mamah Borthwick here. You can see Wright’s home, Taliesin, against the hill.

I wrote that in an email to Taliesin Preservation‘s Programs Director, as well as its Bookstore Manager.

Then I continued:

“I don’t mean big in ‘our’ little Wrightworld. I mean big in the real world.”

It was May 2007 and I had just read about the release of an upcoming book, Loving Frank. Written by Nancy Horan, it is a book of historical fiction with Frank Lloyd Wright and Mamah Borthwick as the main characters.

As August 15 (and the anniversary of Taliesin’s 1914 fire) comes up this weekend, I thought I would write about Loving Frank, and my thoughts on it when it came out.

My first encounter with tales of this upcoming book included newspaper titles with headlines like this:

“They were the Brangelina of their time…”

It catches the eye, you can say that. That sentence, in the Courier Journal newspaper (Lexington, KY), came from Ballantine publisher Libby McGuire, speaking about Wright and Borthwick’s scandalous love affair that made the national news in 1909-1910… 1911-12… and 1914.

And everyone at Taliesin (and all Wright sites) totally wants Brad Pitt (fan of architecture that he is) to take notice and come around.

You’ve seen the photo of Brangelina at Fallingwater, right?

So, in talking about that upcoming book through the summer in 2007, I would jokingly say, “I can’t wait to see the ending!”

Yes, it’s black humor, but what are you going to do?

I mean, I worked at a place where seven people were murdered on August 15, 1914 by servant Julian Carlton in an unknown and unknowable butchering with an axe, and fire (of the seven lives lost, only one died from his burns).

And the summer was full of listening to radio programs with guests discussing Wright and Borthwick. Looking it up, I wrote this in my own journal at that time:

I’m getting tired of reading that Mamah Borthwick is seen as a “footnote” in Wright’s life; or “not dealt with at all,” or “brushed over” or, perhaps, “not dealt with because people feel squeamish,” or that, “she’s not seen as very important.”

It’s not that way for me…, but I get tired of it….

I realize I may be taking this personally.

Me taking something personally? Really? Nah!

But the book came out, which I dutifully purchased. I expected to hate it. Perhaps my view of Loving Frank was reading the word “Brangelina” in relation to Wright and Borthwick.

Perhaps they would be called “Wrightwick”? “Framah”?

The word “Borght”, though, is cute. A Hungarian soup that Björk would eat.

Therefore, I held my breath as I read Nancy Horan’s book. I wanted to hate it, silently checking its facts. And yet I remember, early on, my old boyfriend walking through our living room, asking me what I thought.

By that time I had read, perhaps, up to page 50.

“Well, I don’t want to throw it against the wall,”

I replied.

And, over one hundred pages in, I became impressed by the research done by the author.

For example, in Chapter 21, Wright and Borthwick (who have left their families) are in Berlin, Germany. They have been discovered there by a reporter from the United States; which is true. And upon their discovery, Loving Frank tells the story of how the two became front page news in papers across America. This is also true.

After being discovered, the two leave the hotel and get breakfast. Wright says, “I want to take a little detour over to Darmstadt to see Olbrich, if we can. I’m told his work is worth seeing. Then on to Paris.”1

“Oh my God—she’s read Alofsin,” I said out loud.

I think I even put the book down in amazement.

While in Germany with Mamah Borthwick, Frank Lloyd Wright visited the work of Austrian architect, Joseph Olbrich. In fact, Wright was said to be “The American Olbrich”.

But, then there’s my mention of Alofsin. “Alofsin” refers to Anthony Alofsin. I wrote about him in my post on “Post-It Notes on Taliesin Drawings”. Alofsin wrote a seminal book in Wright scholarship: Frank Lloyd Wright: The Lost Years, 1910-1922: A Study of Influence.2

Alofsin worked on tracing Wright’s movements in Europe

It sounds simple, but it’s not. Wright wasn’t in touch with many people and his movements had to be dug up by Alofsin through Wright’s correspondence (which had recently been indexed3) and Wright’s later statements. So, until Alofsin’s work, Wright’s time in Europe in 1909-1910, was mostly a big hole.

Returning to Loving Frank

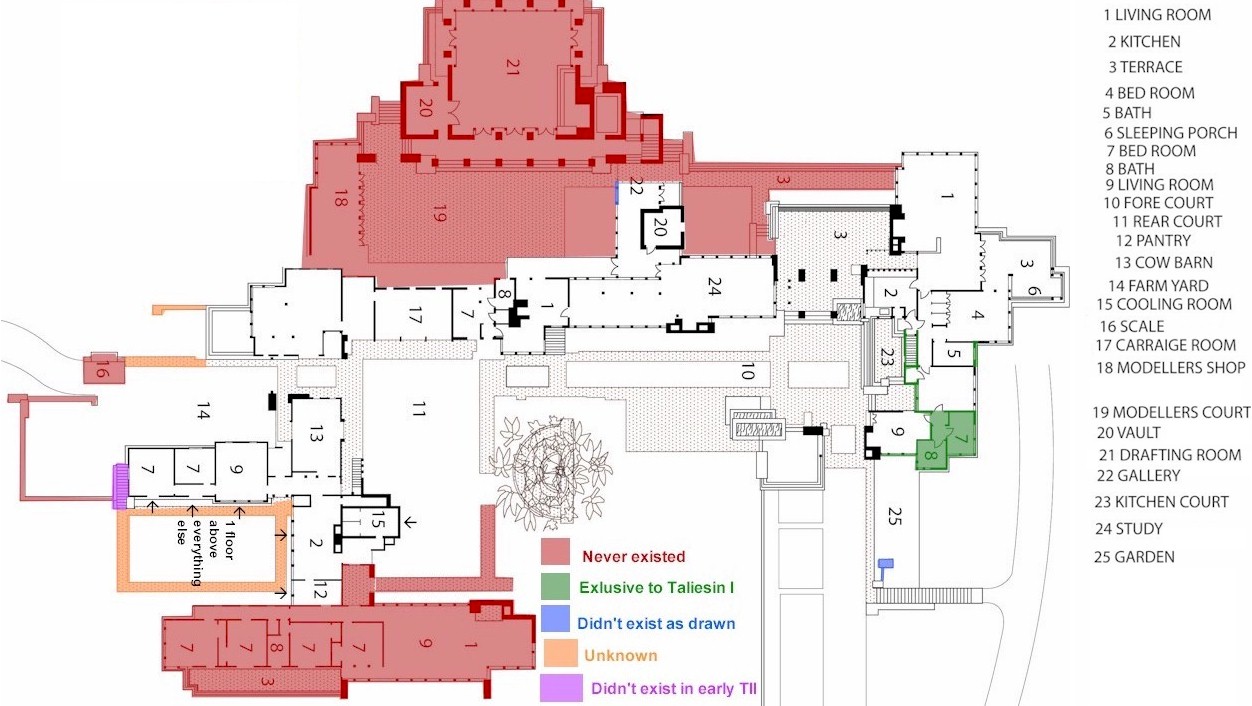

The book sold so well that it inspired a special “Loving Frank Tour” at Taliesin. The first of these tours was done with Nancy Horan, in September 2008 (links on a press release and a poster for the tour are here and here). I was her contact on it, and created the timeline, etc, for the tour. It combined my touring and talking portion, where I told people what they would have seen in 1911.

Then I brought them to Taliesin’s living room, where they met Nancy, who was seated. She then read from the book.

She donated her time to Taliesin Preservation, did a public reading at the end of the day, and did a book signing. Regardless of all that, I found her to be delightful, sincere, and touched by Taliesin.

And, again, I don’t know when, or if, the Loving Frank movie is going to come out, but if he wants to know, both myself, and Nancy Horan’s friend (who came out to Taliesin with her) thought that actor Brendan Fraser should play William Weston (Wright’s real-life carpenter who survived the 1914 fire/murders).

Of course, August 15 is still this coming Sunday.

I took this trip down Memory Lane as more-or-less a distraction from the approaching date. If you want to read my serious take on that day, read here.

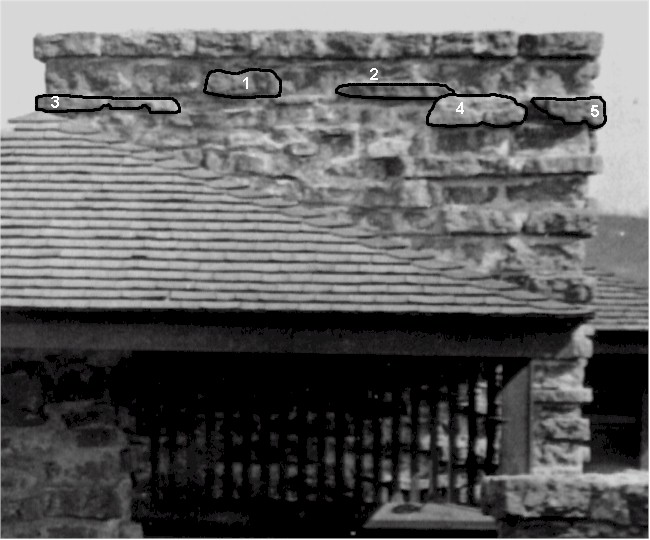

For other photographs of the first Taliesin, and its devastation after the 1914 fire, you can get Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin: Illustrated by Vintage Postcards, by Randolph C. Henning; and Building Taliesin: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Home of Love and Loss, by Ron McCrea.

Originally published August 13, 2021

I took the photograph at the top of this page on August 15, 2005.

1 Loving Frank, by Nancy Horan (Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, New York, 2007), 125.

2 University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1992. I wrote about the book again in my post, “Missing Wright“.

3 Frank Lloyd Wright: An Index to the Taliesin Correspondence is a 5-volume set that was edited under the direction of Alofsin and published in 1988. It’s available at larger libraries.