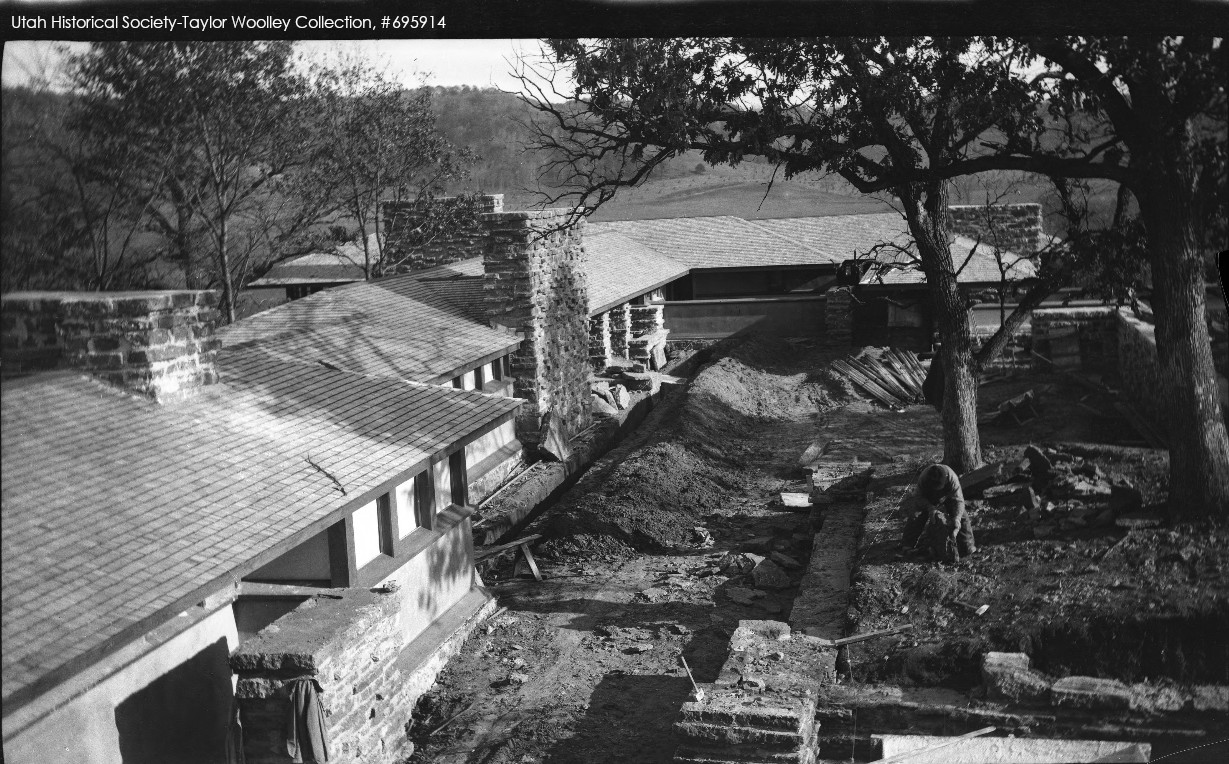

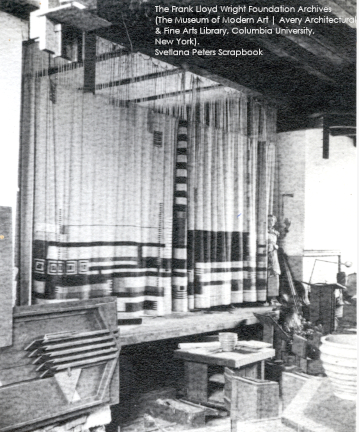

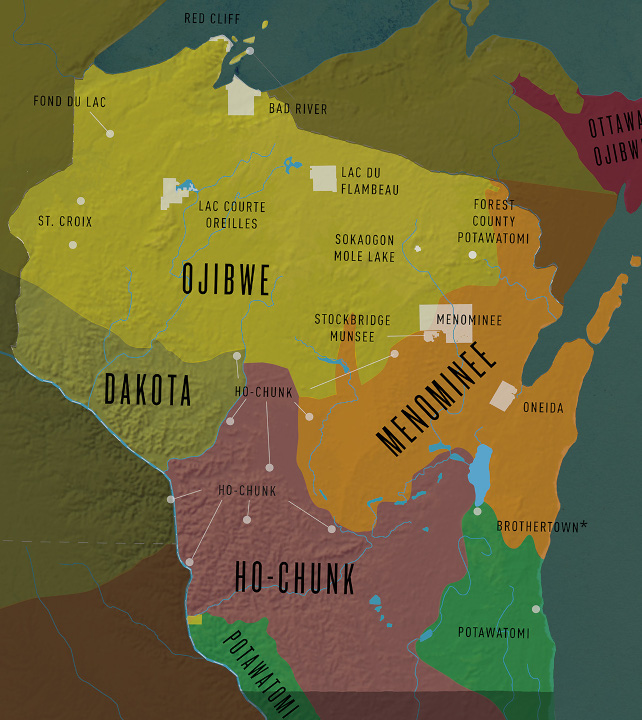

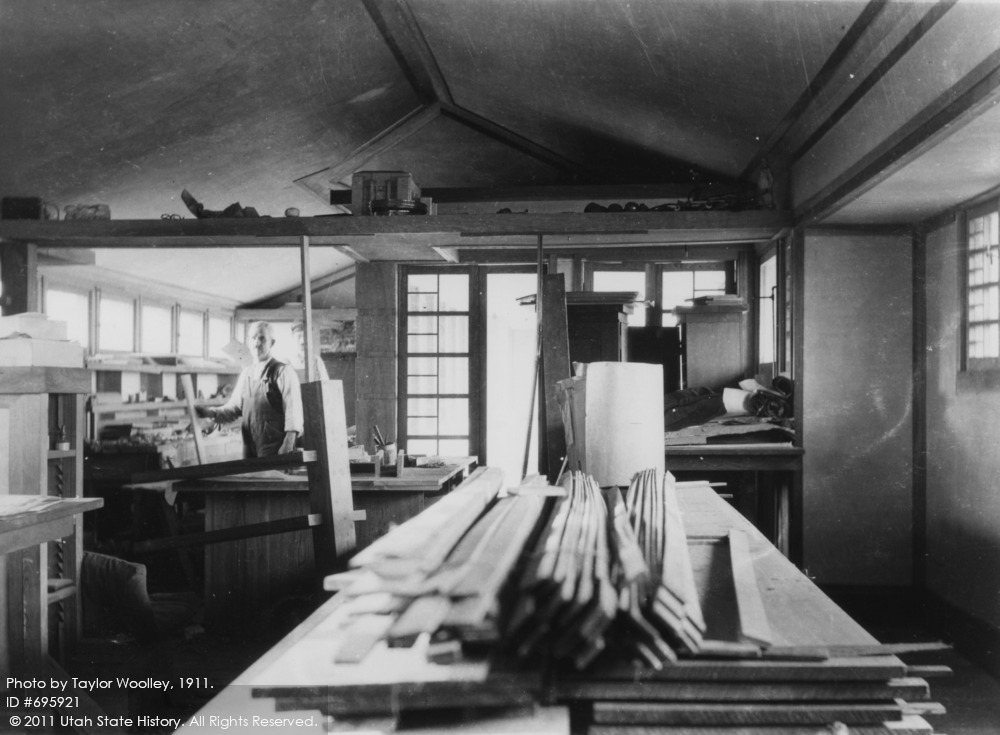

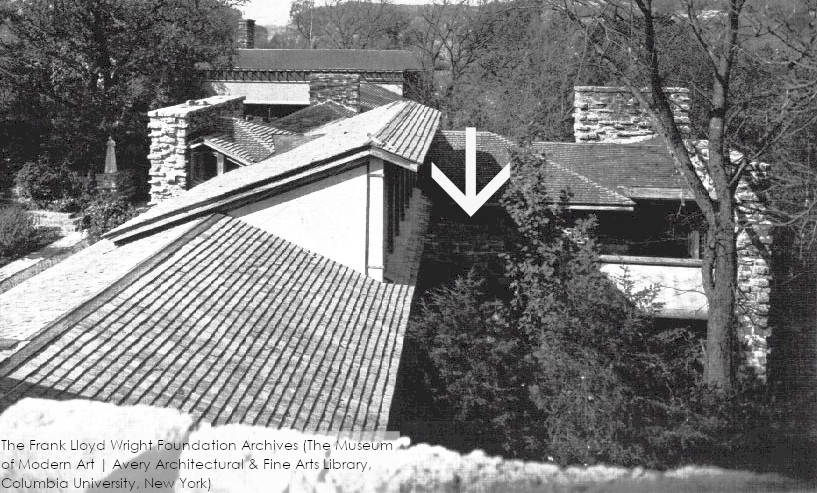

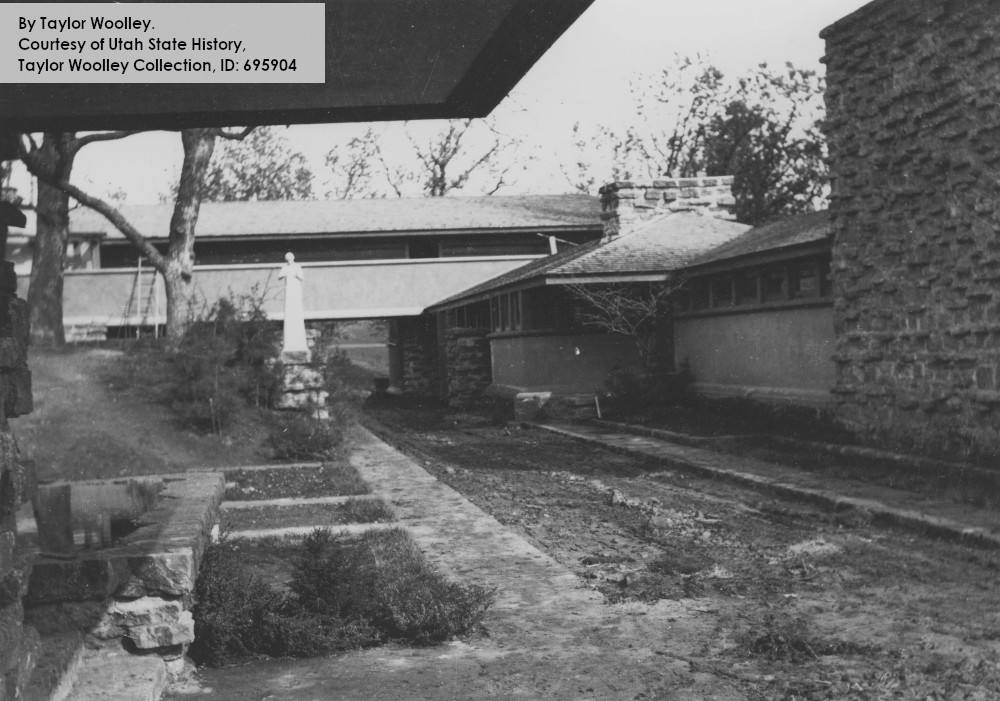

Looking (plan) east at Taliesin from the balcony of its hayloft, fall 1911. Taken by Taylor Woolley, who worked as a draftsman for Wright at Taliesin. I showed this image in the post, “This will be a nice addition“.

While people don’t ask that question at other Frank Lloyd Wright buildings, it’s part and parcel of his personal home in Wisconsin.1 After all, he was already changing things after 1912, and he probably would have made changes at his home even if it never suffered two major fires.

And, remarkably, there are things at Taliesin that go back to 1911-12. Even where there wasn’t any fire.

Why am I bringing this up?

I thought I would share what people asked me sometimes while I gave tours. Hopefully I didn’t overwhelm them with info. But while “don’t talk about what you can’t see” is one of the tour-guiding rules, change was a part of Taliesin.

In fact, that’s true even in the photo at the top of this post. Wright changed almost all of the stone piers and chimneys that you see there.

Now, while Wright didn’t sit down in April of 1911 and say, “I want to change my home with Mamah all the time!”, he liked the flexibility of changing things as he had new ideas. He refined his ideas all the time, and his home was the best place see these new things.

After all, I’ve heard people say that –

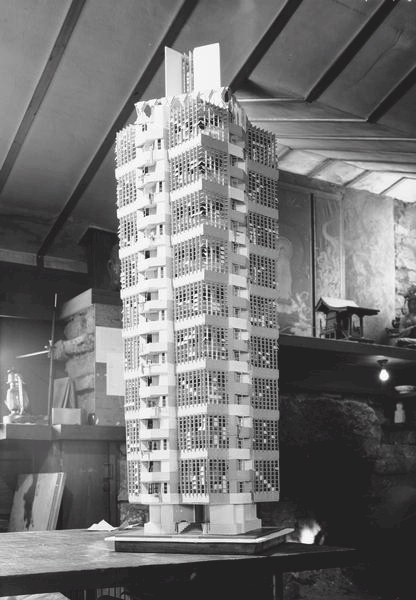

Taliesin is like a life-sized model.

Even Taliesin’s most consistent feature, the Tea Circle, would change.

The Tea Circle

It’s a semi-circular stone bench where Wright and the Taliesin Fellowship used to have tea.

In the photo at the top of this post, the Tea Circle will be eventually built on the right, where you can see the man working under the two oak trees. They wouldn’t finish it until 1912.

So, the photo shows that they had removed all of the dirt around those oak trees, and built the retaining walls. Then they gave the roots of the oaks a chance to settle before making more disruptions.

But Wright’s plans included the Tea Circle at Taliesin almost from the beginning.

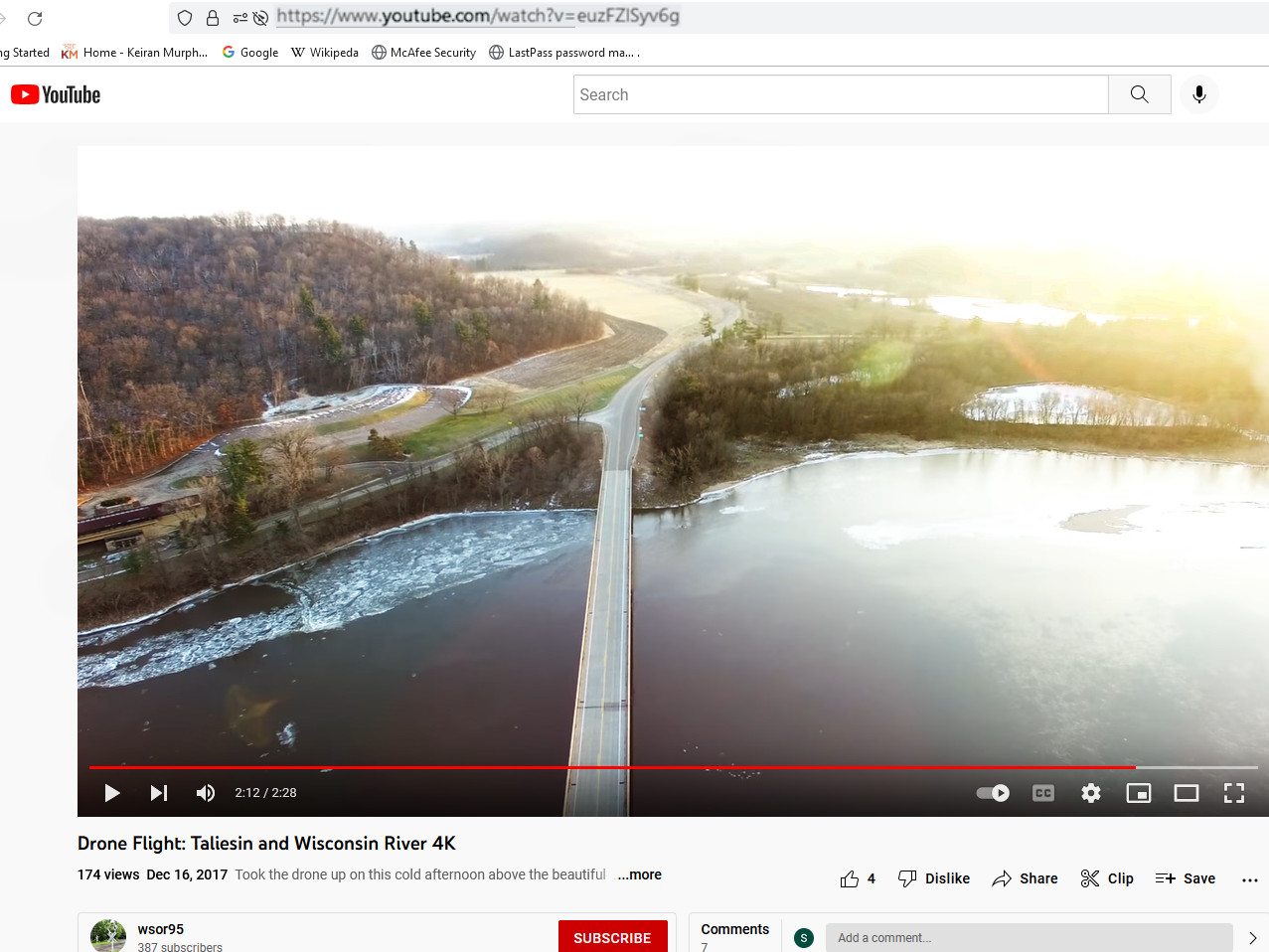

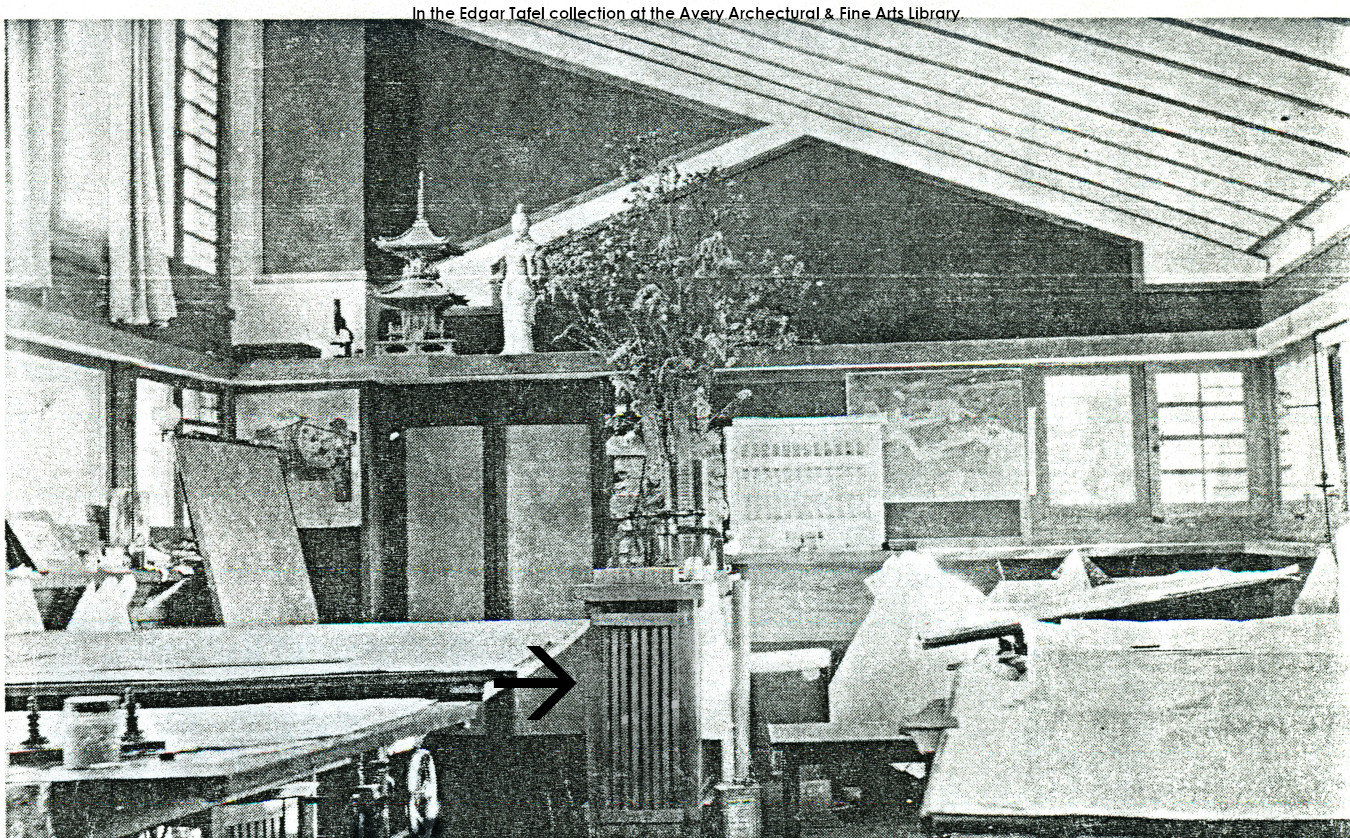

However, you can see that unfinished Tea Circle in another photo by Taylor Woolley, below. He took this in the spring of 1912. Taliesin’s basically been built, but the Tea Circle steps, and its stone seat, don’t yet exist:

Looking west toward the Tea Circle. The chimney at Taliesin’s Drafting Studio is on the right. The Hayloft is under the horizontal roof in the background.

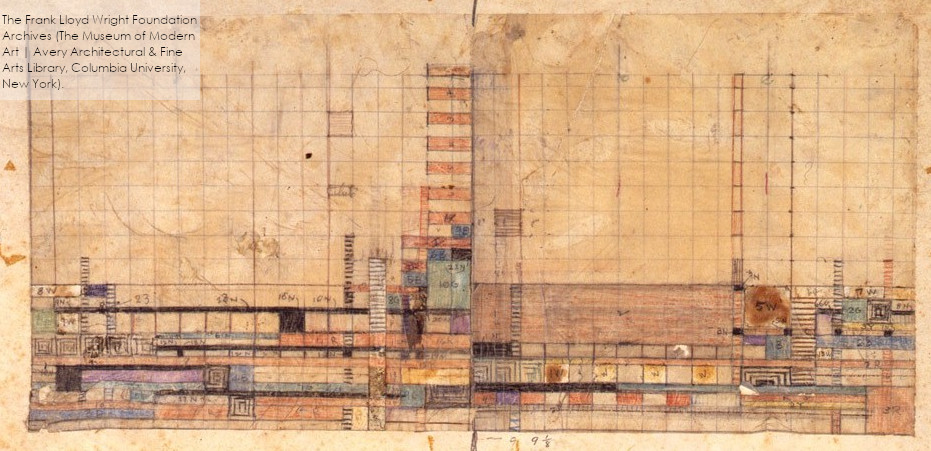

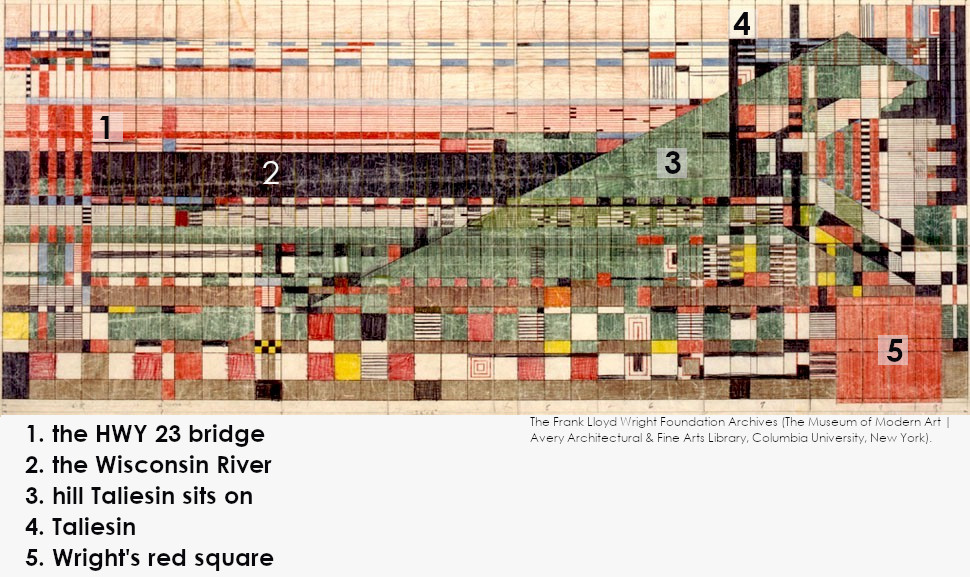

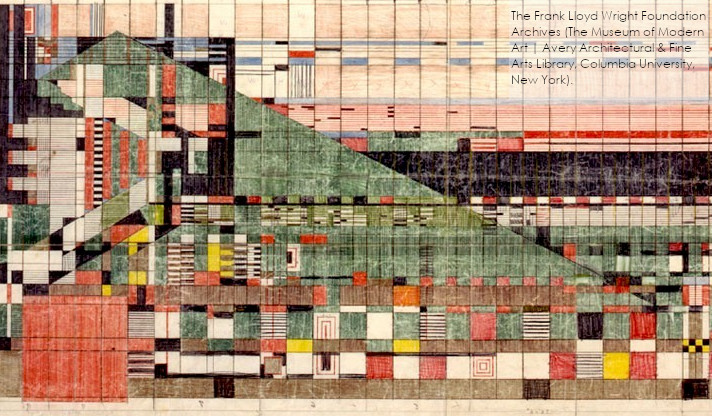

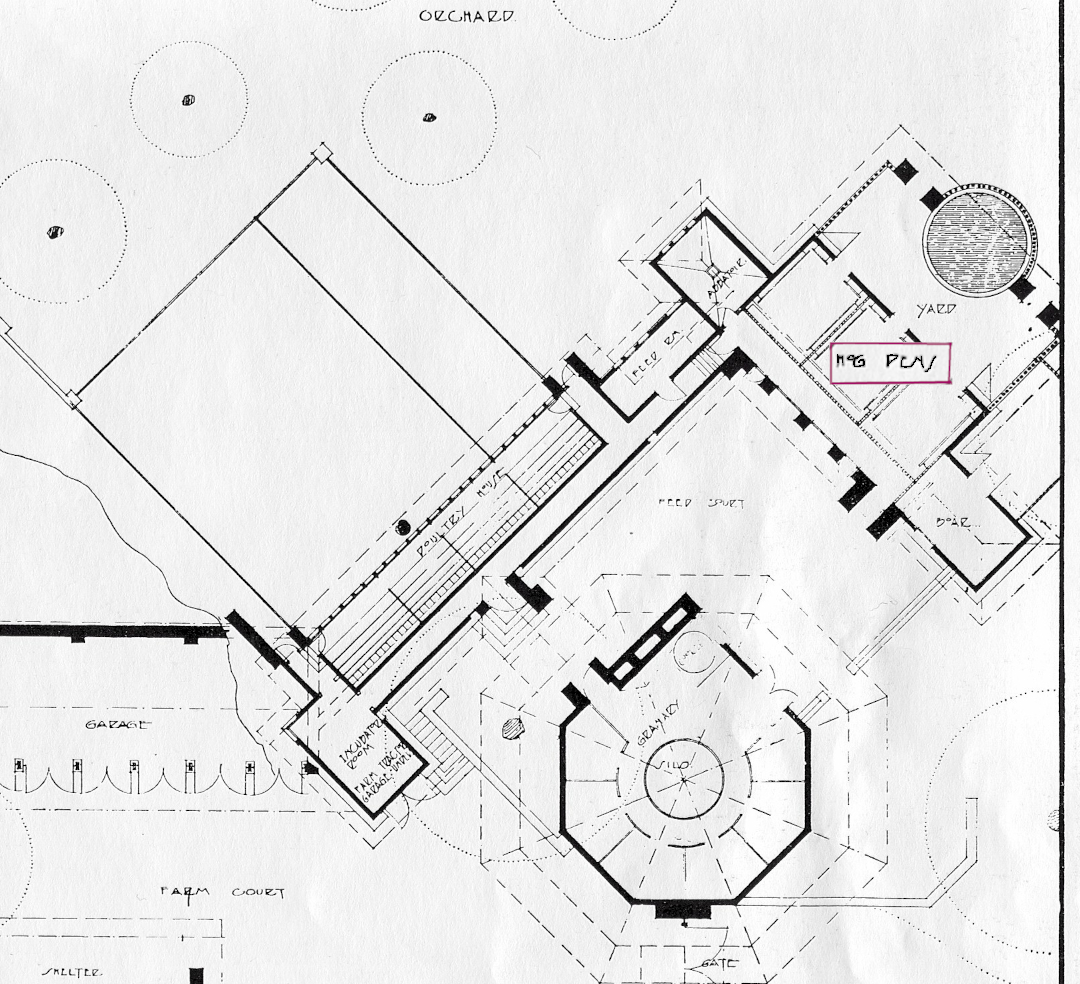

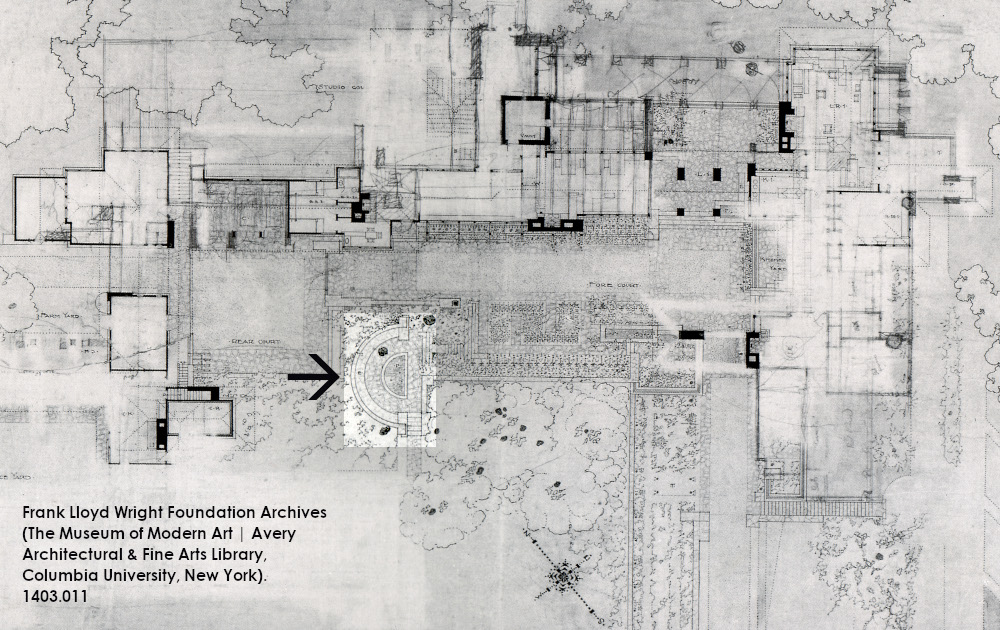

I used to look for the Tea Circle on plans to orient myself when I was first learning about Taliesin. I put one of Taliesin’s early drawing below, with an arrow pointing at the stone bench. Western Architect magazine published this drawing in February 1913:

In fact, here are links to Taliesin plans that have the Tea Circle seat.

JSTOR says the drawings are from Taliesin II, but that’s wrong. I noted before that the former director of the Frank Lloyd Wright Archives, the late Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, was wrong on the structural details of the building. But I never got the chance to talk to him about how he came up with the dates for the drawings.2

The Preservation Crew at the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation carried out restoration, preservation, and reconstruction on the Tea Circle in 2019.3 They had to replace a lot of the degraded/missing stone work there. Its form (and as much stone as possible) now matches what was there in when it was originally finished.

Anyway, here I was,

trying to figure out the date of Woolley’s photo showing the forecourt and unfinished Tea Circle.

that’s the problem with black & white photos: they make late fall and early spring look the same!

And, HOORAY! Wright’s scandals gave me the info.

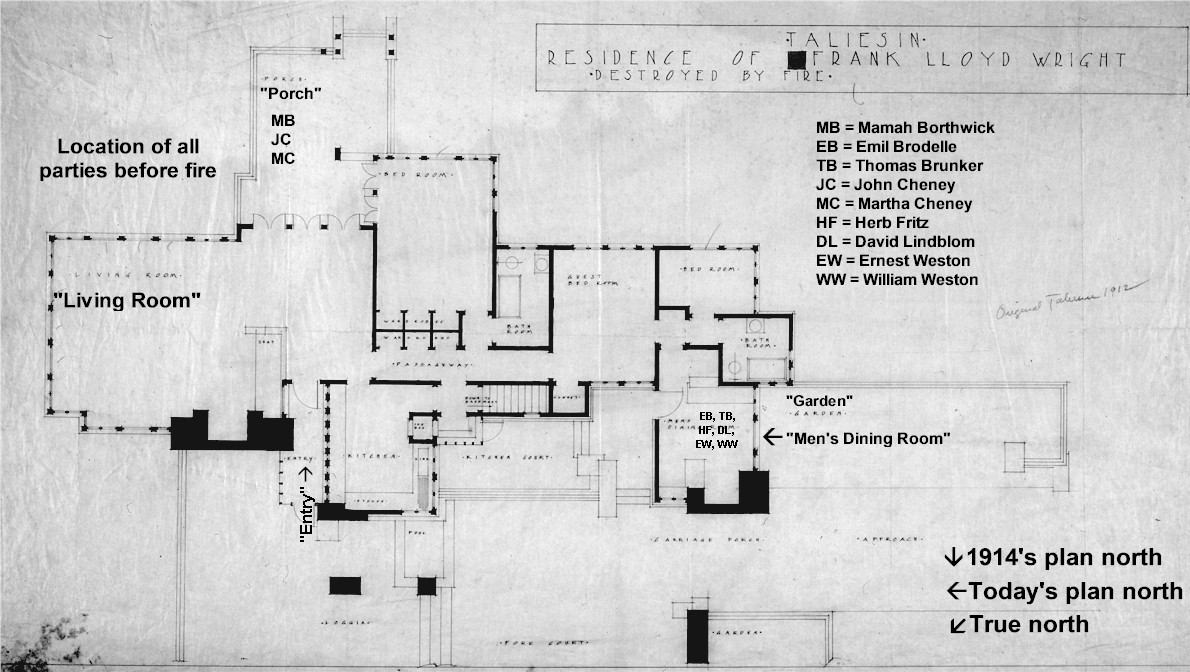

See, on December 23, 1911, the Chicago Tribune sent a telegram to Wright asking to confirm or deny that he was living in Wisconsin with Mamah Borthwick.

(by then, she and Edwin had divorced, and she legally took back her maiden name)

The Tribune published his reply on Dec. 24,

Let there be no misunderstanding, a Mrs. E. H. Cheney never existed for me and now is no more in fact. But Mamah Borthwick is here and I intend to take care of her.

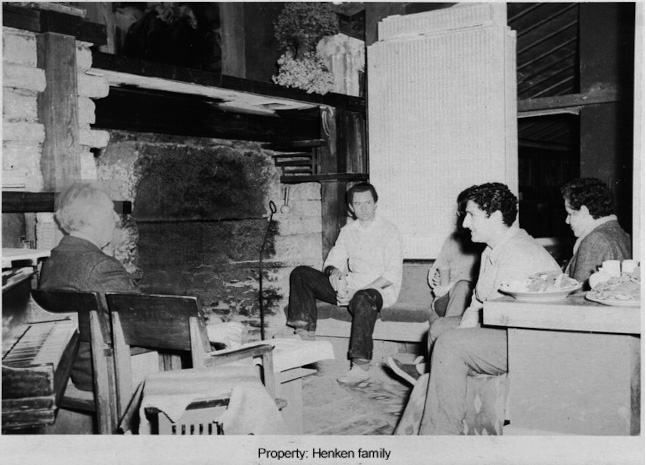

Since Wright’s telegram made things even worse, the next day, Wright and Borthwick invited the reporters inside Taliesin so he could give a public statement. He hoped doing this would explain things and take pressure off himself and his family.

It didn’t go well.

In part because Wright said, “In a way my buildings are my children”. The guy needed a publicist. But it was 1911; whatcha gonna do?

This disaster with the press answered my question:

As Wright escorted the reporters to the forecourt (now the Garden Court), he talked about upcoming work on the building and grounds. He said:

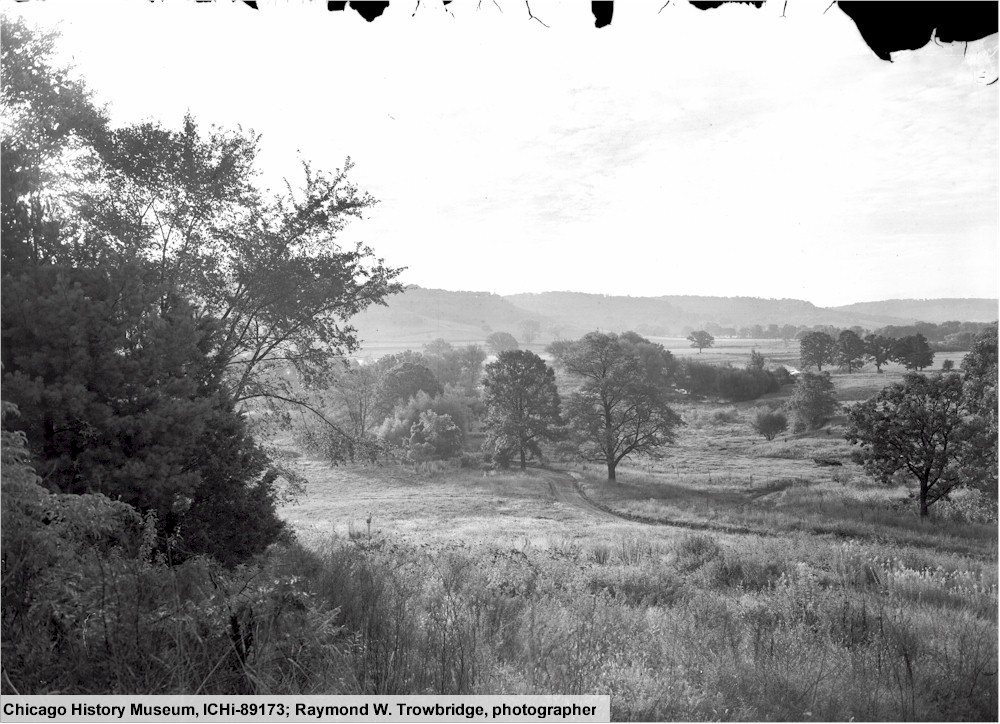

There is to be a fountain in the courtyard, and flowers. To the south, on a sun bathed slope, there is to be a vineyard. At the foot of the steep slope in front there is a dam in process of construction that will back up several acres of water as a pond for wild fowl.

Chicago Daily Tribune, December 26, 1911, “Spend Christmas Making ‘Defense’ of ‘Spiritual Hegira.'”

AHA!

There it is: at Christmas 1911, they hadn’t yet finished Taliesin’s dam! So the hydraulic ram wasn’t yet working to bring water to the reservoir behind the house, giving Taliesin running water and water for the pools!4

In contrast, Woolley’s photo has the fountain (on the left in the photo above). That means the water system was working.

More Taliesin photos

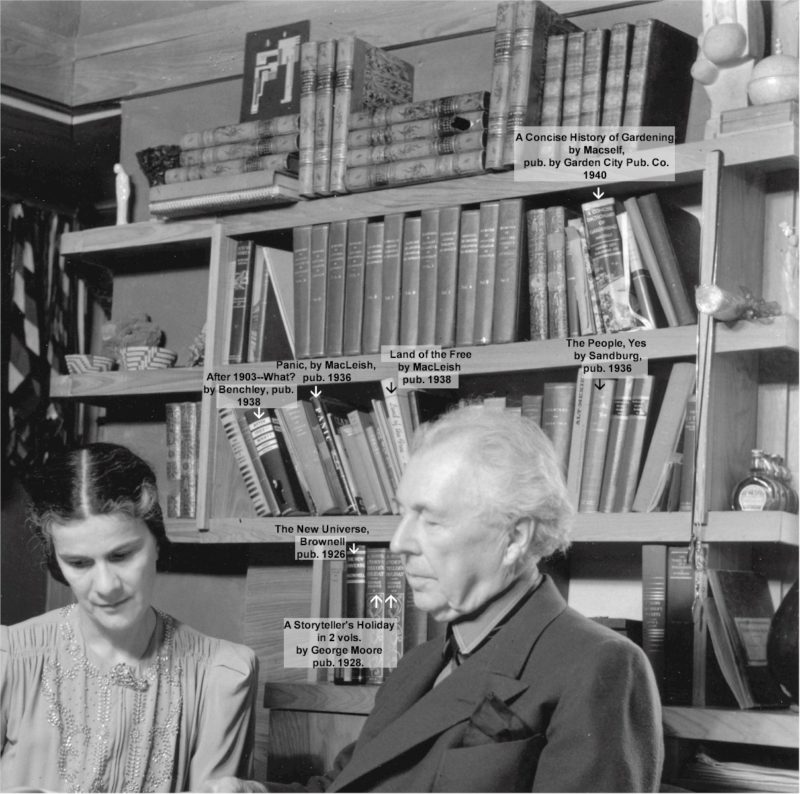

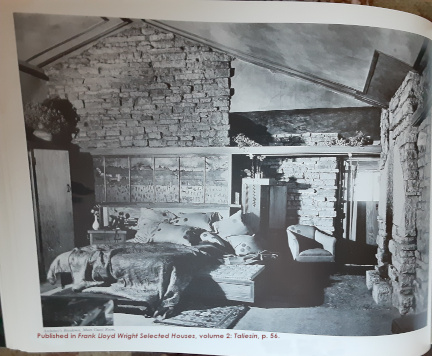

In January 1913, Architectural Record published photos taken in the previous summer. Click on the photo below for the link to a .pdf of that magazine. The link is the whole magazine for the first half 1913, so you’ll have to go through it.

You go to the link (which has 6 months of the issues). You can find page 44 of the January issue, and that’s the start of 10 pages of Taliesin photos, like the screenshot above.

These Fuermann photos are what a lot of people envision when they think of Taliesin I.

You can also find them at the Wisconsin Historical Society in the Fuermann and Sons Collection.

And if you love them and want All The Fuermann Photos, you can buy the special issue on them that was published in the Journal of the Organic Architecture + Design Archives. They’ve got the photos Fuermann took in three photographic sessions. Architectural Historian, Kathryn Smith, explains their history.

More to come

I was ready to post this when I realized there are a few more things that you can see on tours that go back to 1911-12. So I’ll publish another post with more.

Taylor Woolley (then Wright’s draftsman), took the photograph at the top of this post. It’s at the Utah Historical Society, here.

Published November 16, 2022

Here’s “What’s the oldest part of Taliesin, Part II“.

Notes

1 I don’t think they’ll be offering tours underground any time soon, in part because the openings into some places are only accessible by crawling on your hands and knees. Like what I wrote on in “A slice of Taliesin“.

2 I didn’t want to come off as a snotnosed smarty pants. Although maybe we could have talked about it. He seemed to trust my opinion by the end. He respected my opinions on one drawing I asked about.

3 The restoration work is due to a donation by educator and Architectural Historian, Sidney K. Robinson.

Watch Ryan Hewson, of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation talking about the restoration of the Tea Circle the “Frank Lloyd Wright x Pecha Kucha Live 2020” event. Pecha Kucha is a fast-paced slide show, and Hewson’s presentation is just over 6 minutes. It explains the work really well.

4 I wrote about my study of the dam in the post, “My dam history“.