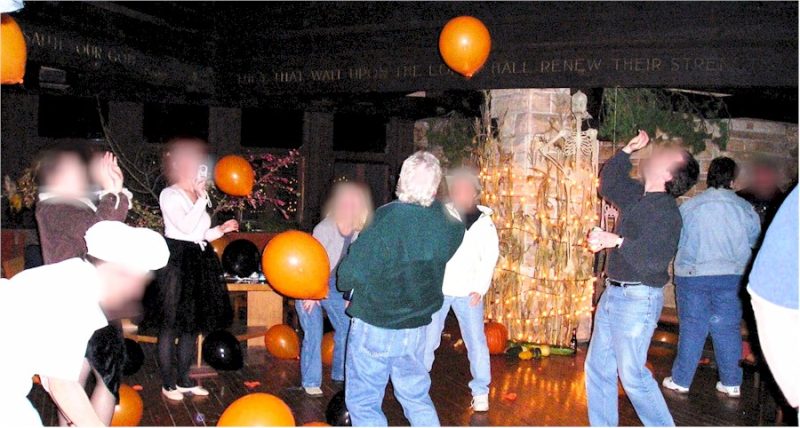

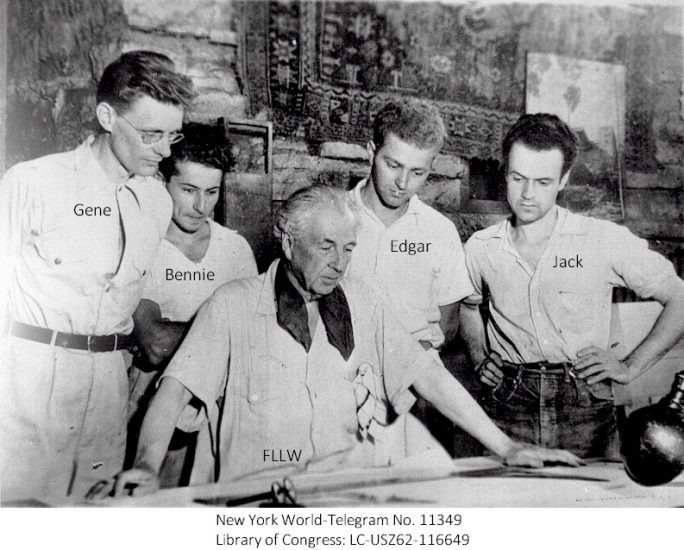

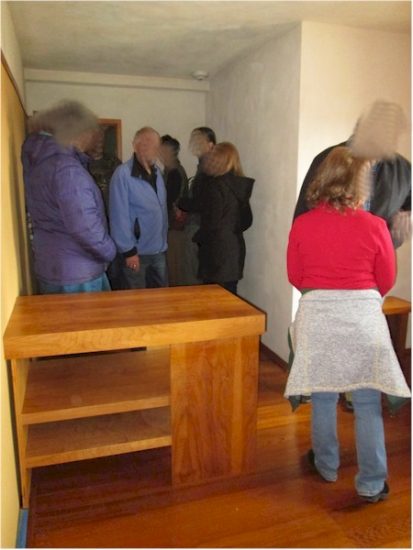

Photograph from the 2000s taken by me in Taliesin’s living room. Looking toward the fireplace with the inglenook (the built-in bench).

Today, I thought about photographs from the book, Apprentice to Genius, by Edgar Tafel that I recommended almost a year ago. Looking through the book reminded me of a change to the inglenook (the built-in bench) at the fireplace in Taliesin’s living room. I’m going to talk about that change in this post.

A moment about Wright’s living room

While I’ve written about his living room before, I haven’t really talked about it much. That’s in part because, while Wright obviously loved it and rebuilt it after his home’s two fires, he didn’t spend a lot of time changing it.

I mean, comparatively speaking.

Because he changed other rooms. A lot. Like the room I talked about in here; I mean, c’mon: it’s inside Taliesin and figuring out where the room stood (or stands. . . it’s still there) can be really difficult.

But, in contrast, there are things in Taliesin’s living room that he kept the same.

For example:

- The door from the main hallway was always in the same space.

- The room always had almost square windows.

- The dining area was always on the south wall.

And,

The fireplace always had an inglenook. In addition, for years (and after each fire), the inglenook ended a bookshelf on the end, farthest from the firebox. Maybe this bookshelf kept the space on the couch warmer when you had a fire.

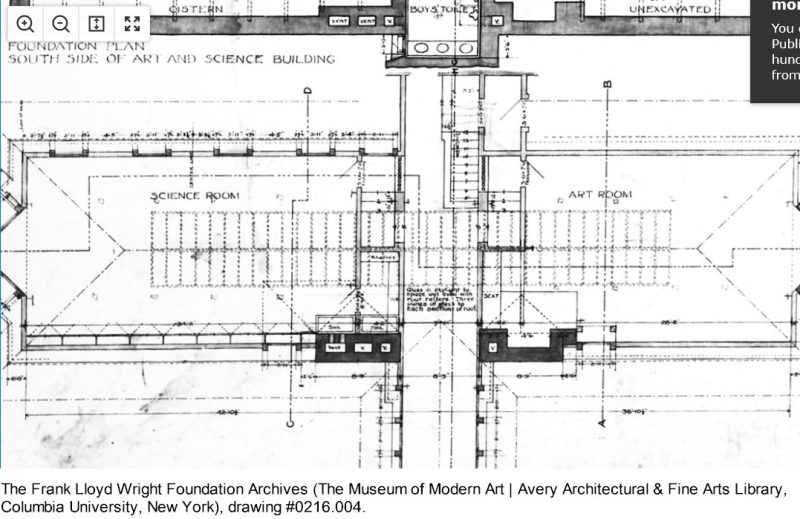

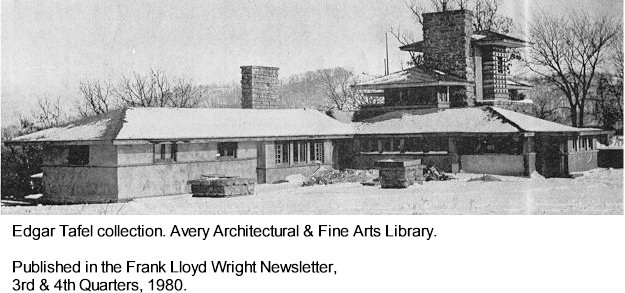

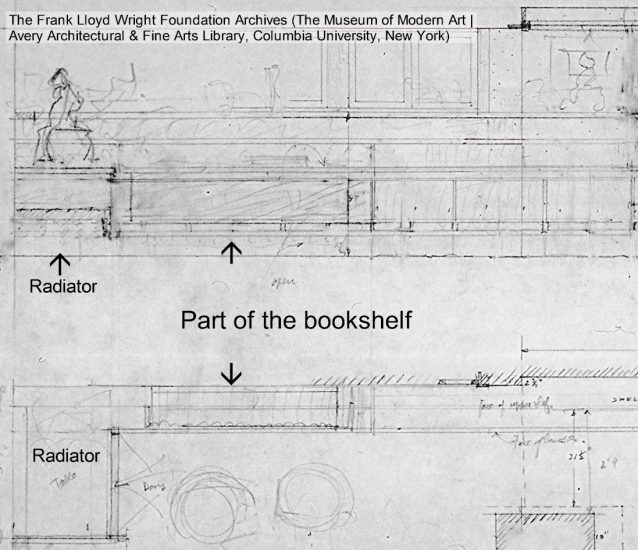

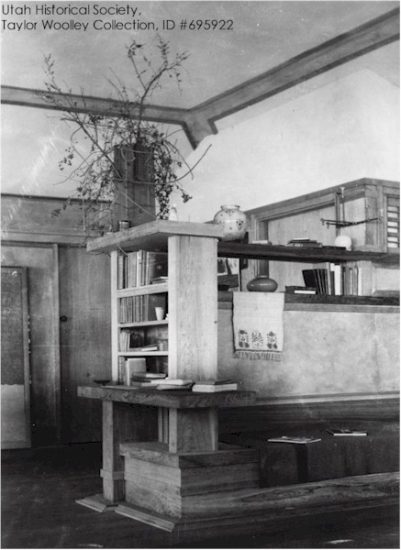

Here’s the inglenook and bookshelf during the Taliesin I era:

Photograph taken 1911-1912 by Taylor Woolley, Wright’s draftsman at Taliesin at that time. Photograph located at the Utah Historical Society, ID #695922.

btw, I have tried to read the titles on the books on the shelf. Unfortunately, when I magnified it, the book titles just got blurry.

The bench was reconstructed for Taliesin II, after the 1914 fire.

Which can see in this Taliesin II photograph from the Wisconsin Historical Society.

And, again, after the fire of 1925.

You can see the inglenook here in an early Taliesin III photo, at Greatbuildings.com.1

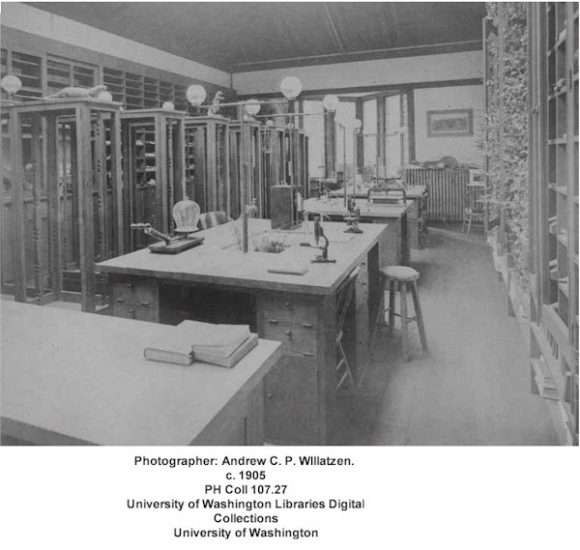

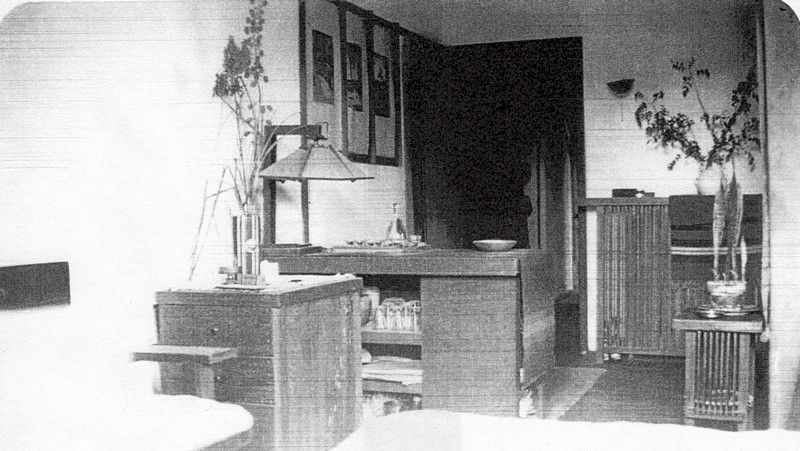

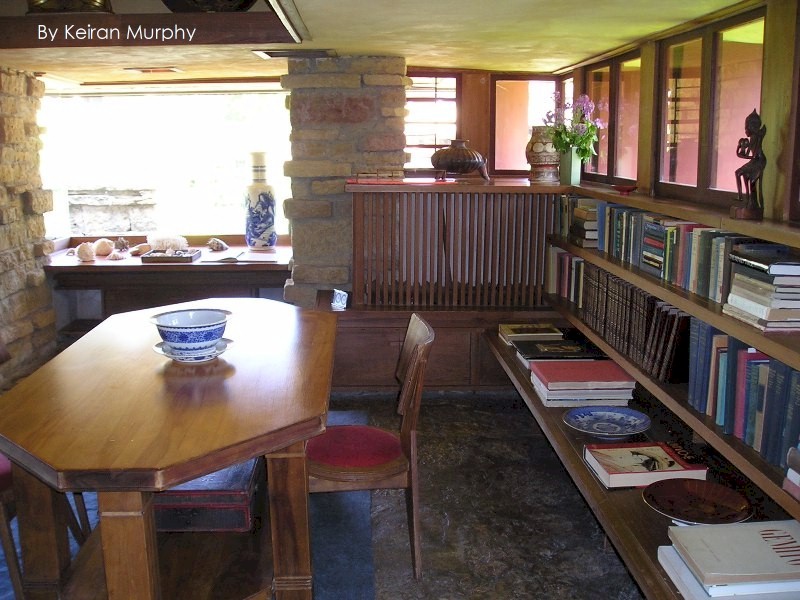

And then we come to one of the photographs from “Apprentice to Genius”. The photograph from it below was taken in 1940 by Pedro Guerrero:

Property: Pedro E. Guerrero Archives.

The bookshelf is the vertical section at the end of the bench.

This photograph is on page 112 of Apprentice to Genius.

In addition, this photograph shows that Wright had a small bookshelf on the opposite side of the bench. You can see the books where the bench terminates into the wall in the living room, to the left of the fireplace mantle.

btw: I’ve looked at the books on that little shelf and can’t read the titles there, either.

I suppose that could be a nice thing to have if you were at that fireplace in the winter, reading.

And then he made changes in the 1940s

Particularly the early 1940s. Why?

Because Wright, his family, and a few others were (more-or-less) confined to Wisconsin after the United States entered World War II. This involvement led to rationing, which resulted in his forced residence of Taliesin again year-around.

In addition,

Being forced to stay at his digs in the Midwest allowed Wright to think seriously on how he could change his home to make it more suitable to living in the summer.

Aside from all those stone changes he made in 1942-43 when he got an offer for “a cord or two of stone for every hour that I use the tractor.”

So, along with large changes at Taliesin, he made changes to this part of the living room.

Here’s what I think happened:

That bookcase probably helped to preserve heat near the fireplace. So, he got rid of the bookcase, since he wouldn’t have to worry about conserving heat there any more, once they could all get back to Taliesin West in the winter. Besides, taking away that bookcase would make the bench more open to people walking around during hors d’oeuvres for Sunday formal evenings.2

He also eliminated the little bookshelf to the left of the fireplace, and put mortared stone in its place.

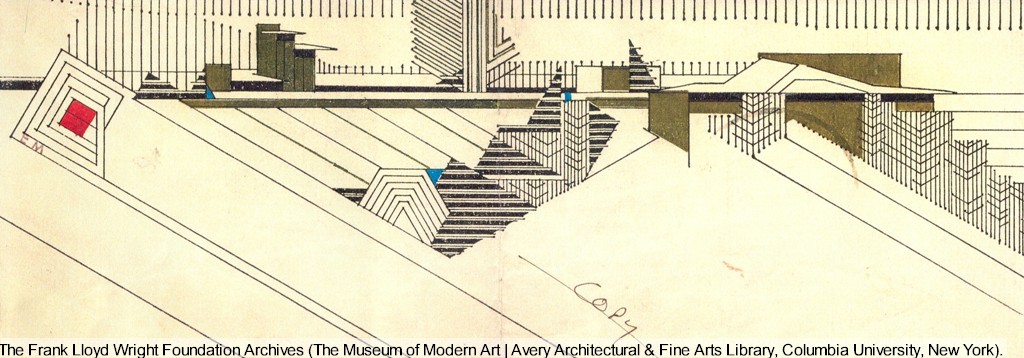

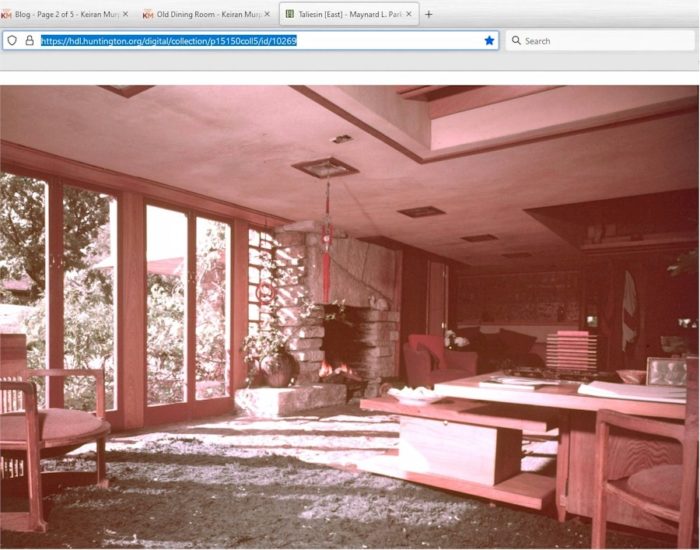

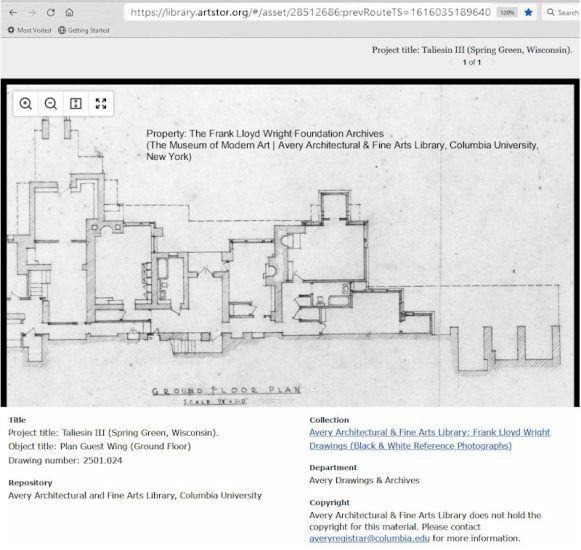

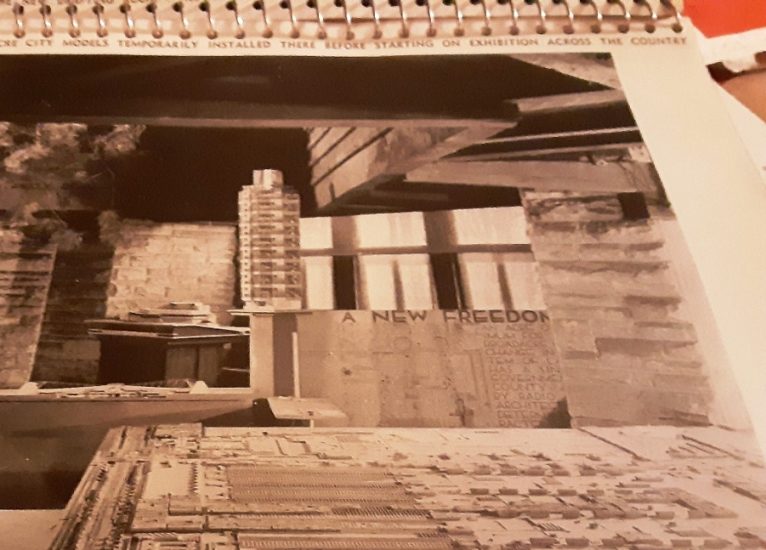

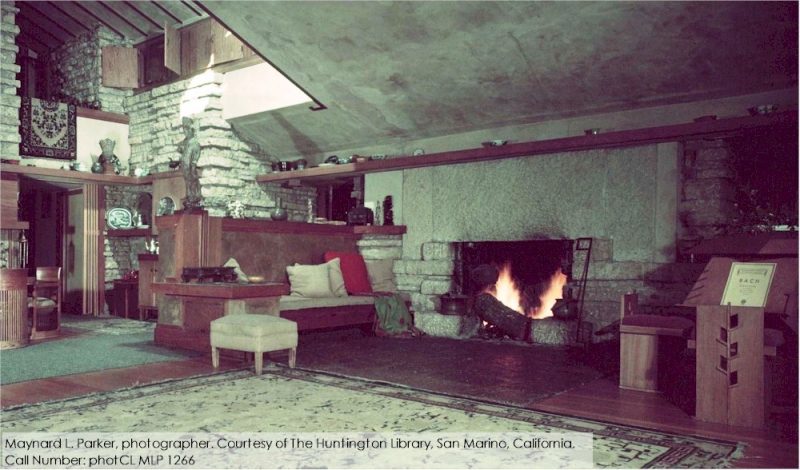

The removal of both book storage areas, were just two of five or six changes. You can see the cleaned up area in Apprentice to Genius, p. 113. Or in the photo below taken in the 1950s by Maynard Parker. Parker Taliesin took photographs at Taliesin in 1955 for House Beautiful.3

Call Number: photCL MLP 1266

Now:

I do not know if Wright thought of the changes near the fireplace all at once, or if he made a change at the bookcase, followed by others over time.

Like when you go to wipe up a coffee spill on the counter and three hours later you’re mopping the entire kitchen floor after having wiped down all the cupboards while you rearranged (and threw out) the old spices (oh, you were so naive when you thought you’d use that much Cayenne).

But, maybe this came to him fully formed. From the bookcase, to the mantelpiece, or maybe the mantelpiece to the bookcase.

And, yes,

That photo shows a water stain on the ceiling. One time, a Taliesin Preservation employee (hey, Bob!) said to us that leaks in Wright buildings were like Alfred Hitchcock making a cameo appearance in his movies.4

I also like the plaster on the back of the built-in: sort of dark gold. I haven’t determined whether he made it lighter the last summer he lived in Wisconsin. Although, one of his former apprentices, David Dodge, said one time that Wright had apprentices redo colors on the walls every year. Although I don’t know if that was for every square inch of every wall in every space, but “David” said he could see why Wright redid the colors.

David said that just because the same flowers grow in the same place as the year before doesn’t mean the red or yellow of that rose will be the exact same shade in every way.

First published March 16, 2022.

Notes:

1. This photograph is published in the Volume 6 Number 1 issue of the Journal of the Organic Architecture + Design archives.

2. Formal evenings were held every Sunday when I started in 1994. Why they were held on Sundays, I don’t know. They were definitely Saturdays later and were held two times a month after I’d worked a season or two.

3. House Beautiful magazine, November 1955, v.97, number 11, p. 233-90 +. Parker gave his collection to the Huntington Library in California.

4. Although I can tell you that, this part of the ceiling has never leaked in my experience with Taliesin. And, while work has always been done to stop them, the roofs of Taliesin do/can leak. I recall one day maybe a dozen years ago, when TPI’s then-executive director told a reporter with excitement that, “Nothing leaked this spring!” [paywall] It’s not that Wright didn’t know what he was doing; he was just always changing things. So he was putting “creases” in the “envelope” of the building.