A stone wall on the north side of Taliesin’s entry foyer. Based on the red wash across most of the stones, the bottom of the wall survived Taliesin’s 1925 fire.

Sometimes, while working at Taliesin (as I wrote once before), my answer to the question, “What did you do at work today?” was, “I looked at stone.” I’ll explain that here, because it engendered some interesting conclusions.

In order to understand that, you’ve got to know Frank Lloyd Wright’s stone at Taliesin.

(what? You didn’t think I’d say that?).

It should be no surprise that Wright employed local stone when building his home; the stone came from about a mile down the road to the north. And, as he built his home in Southwestern Wisconsin, he had plenty of dolomite limestone indicative of the surrounding Driftless Area. He used it in Taliesin’s foundations, chimneys, walls (when he didn’t use plaster or glass), and flagstone floors.

He also wanted it laid a certain way

The stone had to be in the same orientation that was in the quarry (it was kept horizontal; not orientation like facing east or south, etc.). And, on walls, he told the masons to vary its depth. This way, it would echo the look of stone outcroppings (and is gorgeous with snow on it). You see the snow on the stone in the photo below from my entry about newly seen photos:

Posted in a “Flashback” article from December 4 by Ron Grossman at The Chicago Tribune: “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin was a refuge for illicit romance. But tragedy tore apart the love he built.”

Hey, at least he took notice:

Wright later wrote that the stonemasons –

[L]earned to lay the walls in the long, thin, flat ledges natural to it, natural edges out. As often as they laid a stone they would stand back to judge the effect. They were soon as interested as sculptors fashioning a statue. One might imagine they were, as they stepped back, head cocked to one side, to get the effect.

An Autobiography, published in Frank Lloyd Wright Collected Writings, volume 2: 1930-32. Edited by Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, introduction by Kenneth Frampton (Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., New York City, 1992), 227.

This wonderfully unique stonemasonry allows you to see crags and details of individual stones from a dozen or so feet away. As a result, I learned to “read” the walls, quickly finding their stone configurations to follow through time. I mean: pick a stone (or several) in a wall, and see how the building changed around it/them—walls getting longer or taller; things appearing and disappearing.

Although, honestly, it’s easier to figure out when the walls got longer. You can see the vertical lines in the masonry when Wright had stonemasons (and, later, his apprentices) expand the walls. While it seems that Wright wanted things done quickly, both I and others have thought that Wright also wanted people to know the changes that were done.

How I figured this out

I first studied the individual stones when I began writing the history of one room at Taliesin, the Garden Room.1

Its chimney has been in the same location since Wright started his home in 1911. But a former coworker, looking at the chimney in archival photographs, concluded Wright must have completely rebuilt the chimney after the first fire of 1914. That’s because the stone didn’t match what was under its capstone.

Originally, I was set to put what she wrote into my historic doc.2 But then I asked myself: did Wright completely dismantle the 1911-14 chimney? I had the archival photos, and the time, so I started to study them (probably with a magnifying glass and/or a loupe).

I discovered that the chimney today, while changed, is the same chimney that existed in 1911. After Taliesin’s 1914 fire, Wright made it taller and that’s what confused Kelly. I’ll show the images below with the stones pointed out (with “circles and arrows on the back of each one explaining what each one was…”).

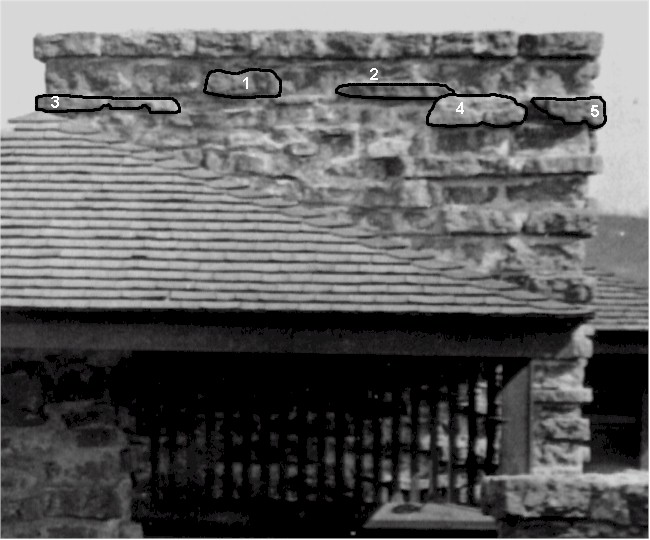

Someone took this photo of the chimney below in the Taliesin I era:

Looking east at the chimney for what became the Garden Room (in the foreground) with stones pointed out. Photo owned by Wisconsin Historical Society.

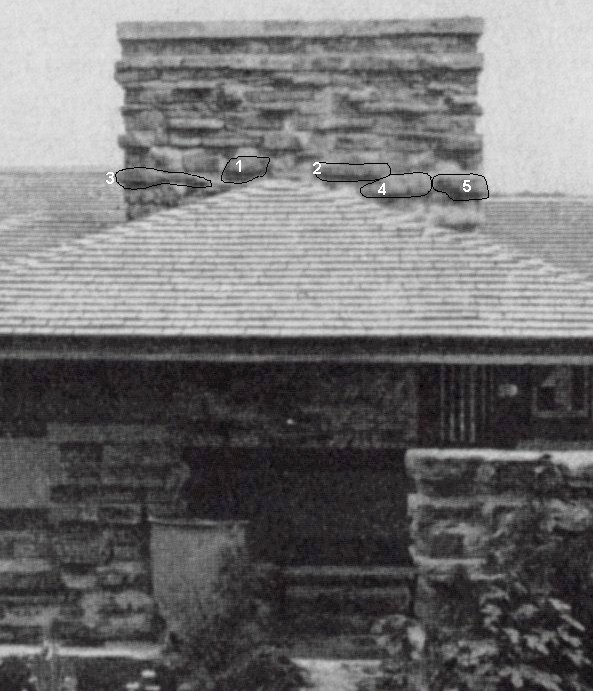

Then, look at the photo below from the Taliesin II era, with the stones, again, circled and numbered:

This photograph was originally published in 1915. It can be found in multiple places, included at the Wisconsin Historical Society, here.

You can see in the photo why Kelly got confused: there are two capstones (two horizontal lines) in the photo taken in 1915. She tried to match the stones under the lower capstone with what existed in 1911-14. But no. They must have heightened the chimney while constructing Taliesin II, and then Wright decided, “it needs to be a little higher”, so they added a few stone courses. Fortunately, I figured this out because I looked until I found the correct stones.

Finding stones that way was probably the first time I did that (and the first time I spent that much time staring at stone).

This work, and more like it, eventually trained my eye to catch things. And, not just with individual stones: it trained my eyes to find specific stone groupings/configurations. Now I can look at an old photo of a wall, see one squarish stone and two little ones to the right, quickly find that place on the wall IRL, and know where I am. It’s like one of those tricks I talked about last time that makes me sound like a magician.

On the Other Hand

One of the easiest things to find at Taliesin are its wall sections that went through one of the fires (most likely the second fire). See, the limestone at Taliesin has iron, which turns red when it goes through fire. It can be quite lovely.

Taliesin walls that survived the second fire are all red (those built after the fire have select, red, stones built into them). A photo of one of the walls that went through the second fire at the top of this post.

First published July 29, 2021.

I took the photograph at the top of this page on September 1, 2003.

Notes:

1 There’s a “Garden Room” at Taliesin West, but that Garden Room is Wright’s living room at his winter home in Arizona (here’s a link to a photo of it). This Garden Room (the one in WI) is not his living room. It’s the former porte-cochere that Wright turned into an informal sitting room in the 1940s. I believe Wright called it the Garden Room because it looks out onto the Garden Court.

2 As I wrote on July 23, this is done in the hope that I did this work so, say, in 20 or 50 years someone else won’t have to.