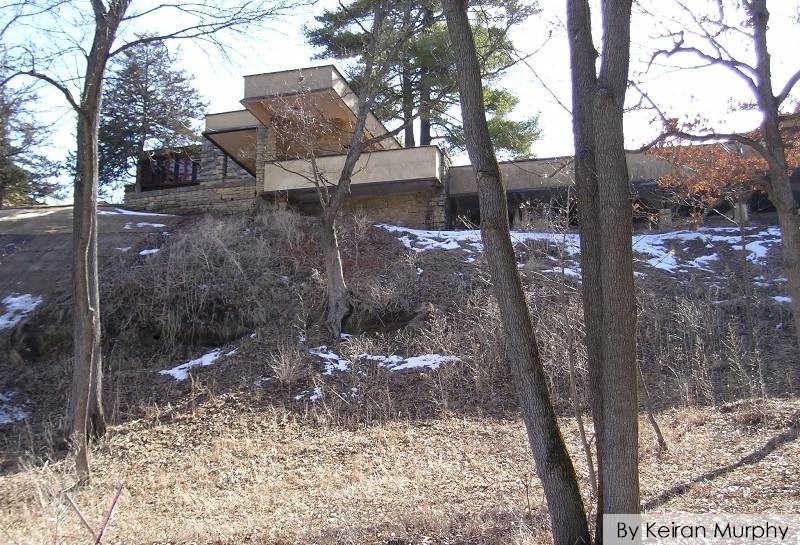

Looking (true) west toward the Taliesin estate from the edge of the parking area of the Frank Lloyd Wright Visitor Center.

I’m working on my next post. So, I figured I would throw out easy dates and pieces of information about Wright and Hillside to give you a little amusement.

Wright’s height:

5 feet, 8-and-a-half inches tall (1.74 m).

That’s what they tell you when you go to the Oak Park Home and Studio. His passport in 1905 has that height, and it makes sense to me.

In addition,

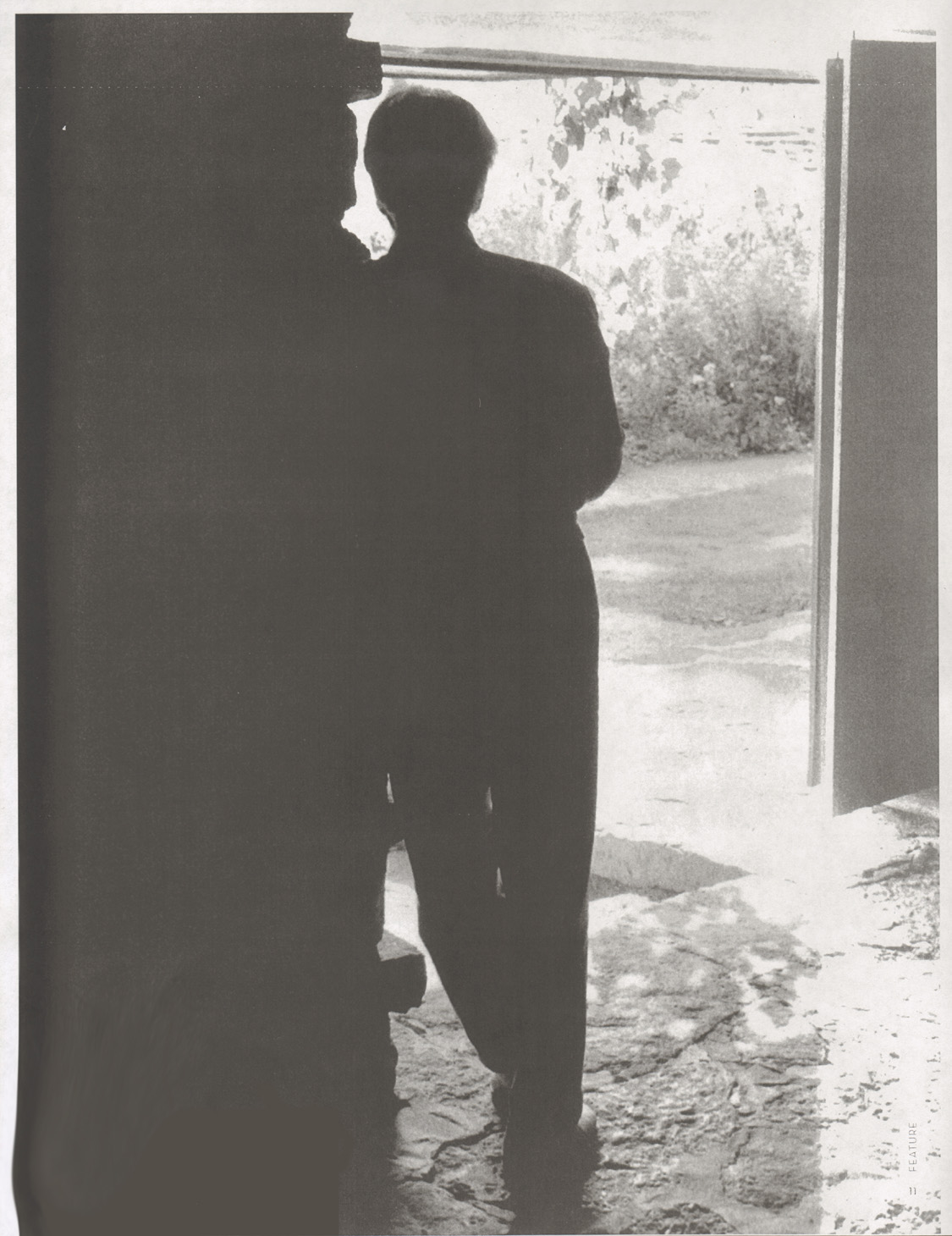

His height in the photograph below might help to prove it. It was published in 2014 in the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly (the publication from the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation):

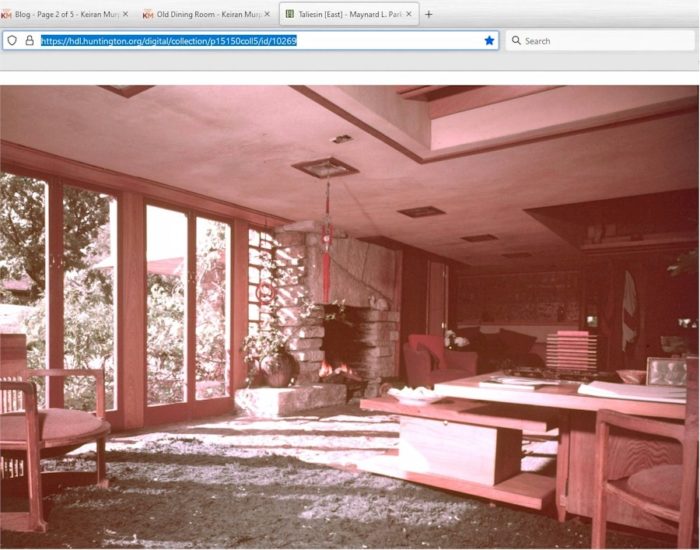

He’s standing against the big stone pier in Taliesin’s Breezeway with the Taliesin Drafting Studio to his right.

When I saw that photo, I grabbed a tape measure and drove up to Taliesin. I realized the pier could be used as a way to figure out the man’s height. When I got there, I measured the height from where he was standing to the bottom of the stone that you see above his head that sticks out a little bit from the pier.

The height to the bottom of that stone was—I SH*T YOU NOT—5 feet 8 inches tall.

Now, he was leaning a little, and the angle is different and other things have changed, but that was the height.

I remember it because you remember something 5’8″ tall when it comes to Wright.

I can’t tell you his shoe size, though.

Ok, onward:

What day was Wright born?

June 8, 1867 (I wrote about it on this page).

What color was his hair?

Brown, before it went white.

His eye color? His son, John Lloyd Wright, when describing his father, wrote:

“Brown eyes full of love and mischief, a thick pompadour of dark wavy hair – that is my father when I think of him as he was when I was very young.”

John Lloyd Wright’s book, My Father, Frank Lloyd Wright (Dover Publications, 1992; first published as My Father Who Is On Earth, in 1946), 25.

However,

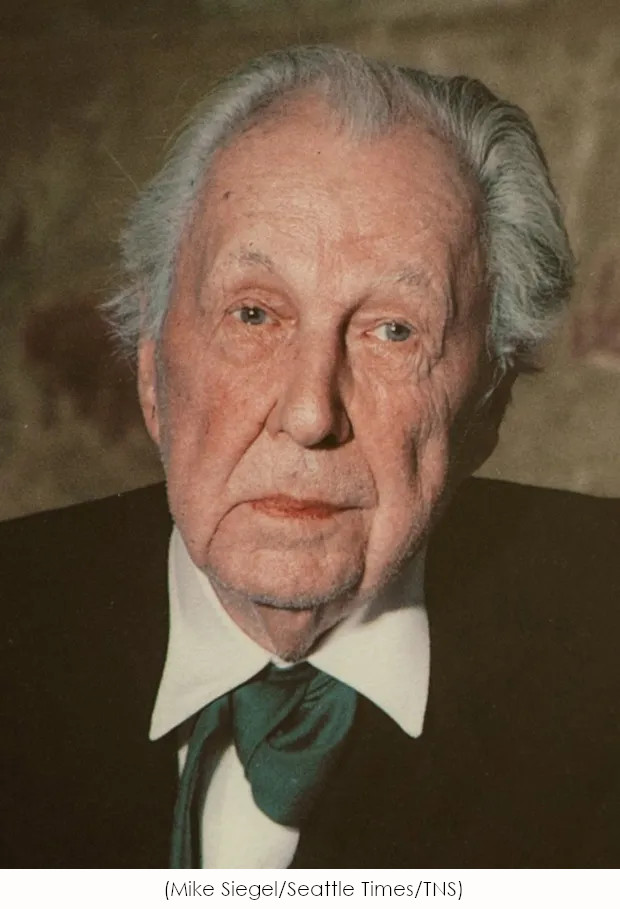

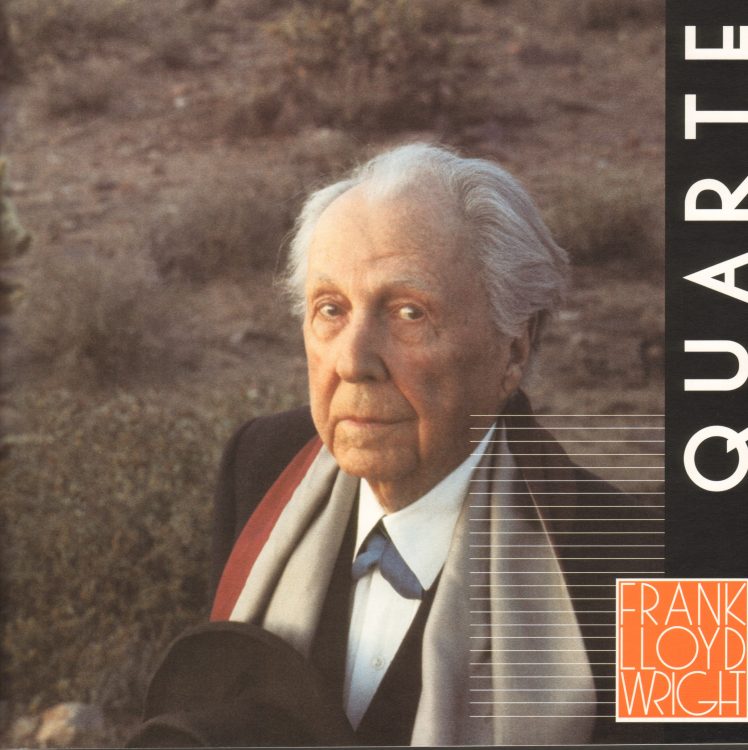

in this 1959 photo taken at Taliesin West, Wright has distinctly non-brown eyes:

And then there was this color photo on the cover of the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly. His eyes look light brown. What the hell:

It appears the two photographs were taken on the same day.

Regardless, perhaps John remembered his father’s eyes being brown, but apparently your eye color can change, which makes my musing moot.

Did Wright ever talk to his dad after his parents split up?

(they divorced in 1885)

Apparently not, according to biographer Meryle Secrest.

And apparently, he didn’t go to his father’s funeral. Wright’s dad, William Wright, died on June 6, 1904 while living with one of his other sons in Pittsburgh. Architectural historian Robert Twombly noted that in his biography on Wright.

His father isn’t buried in Pennsylvania: his remains are in the Brown Church cemetery in Bear Valley, Wisconsin, about 20 miles from Taliesin. Of course, in 1904, Wright lived in Oak Park, IL.

Yet,

Wright didn’t go to his mother’s funeral, either. She died on February 9, 1923 and is buried at the Unity Chapel cemetery within sight of Taliesin. There’s no evidence that Wright was at her funeral. It’s hard to believe it since the chapel is down the road from his home, so it makes me think he was in California working.

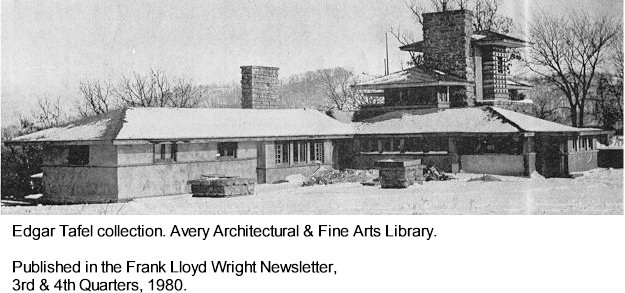

Now let’s look at Hillside

The building on the Taliesin estate that Wright originally designed for his aunts in 1901.

Did Wright design furniture for it?

Apparently not. It doesn’t show up in photos or the few drawings that still exist for the building.

Plus,

I searched for them, just in case there were drawings that hadn’t been recognized in his archives. I did that in 2009 while Anne Biebel (principal, Cornerstone Preservation) and I were working on the Hillside Chronology.

That’s how I ended up finding the drawing of Taliesin 1 for the first time.

I wrote about the second time I found a Taliesin drawing, here.1

Did Wright ever design stained glass for it?

No.

Even though he was doing lots of stained glass designs at that time, Hillside just had diamond-pane glass.

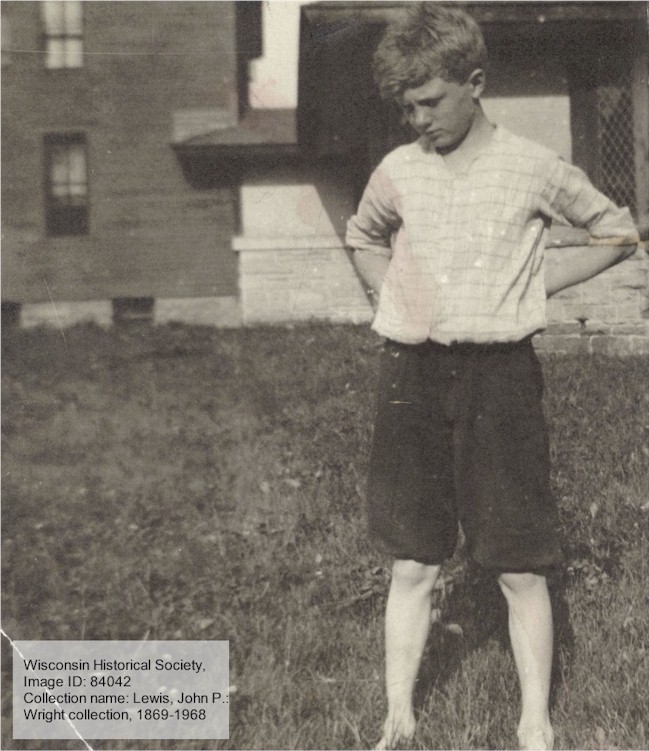

It’s economic, and Hillside was (is) in the countryside. Here’s a photo showing a boy outside of the building. You can see the the glass on the right hand side of the photo:

Image ID: 84042

You can see the photo in my post, “Another Find at Hillside“, which explains the building on the left hand side of the photo.

Will the diamond-pane glass at Hillside ever come back?2

No.

Wright began looking for replacement glass at Hillside while prepping for the Taliesin Fellowship in the summer of 1932. So he definitely did not want the diamond-pane glass there.

On July 20 of that year

his first letter (ID: M031B09), to Mautz Paint and Glass Co. in Madison, Wisconsin (now owned by Sherwin Williams) apparently went unanswered.

Neither did

the letter (ID# P015A05) written on August 23 to the Patek Brothers in Milwaukee.

However,

they had luck with the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company, which sent glass to Wright and Hillside on December 20 (as seen in ID #P018B05).

I do not know how Wright paid for it, but the shipped glass might have been in the condition that Wright first asked for from the Mautz Paint and Glass Co. The letter to that company asked for glass that was once known as “cull-plate,” or any “second hand plate in any proportion.”

Sounds like he was trying to get rejects, or returned glass. That way he could have done it by just paying for the shipping.

Wright could have changed the glass later when he had money, but he didn’t. So, again: the diamond-plane glass isn’t coming back.

First published December 18, 2023.

I took the photograph at the top of this post in March 2004.

Notes:

1. Someone should pay me to do this stuff since I’m so good at it.

2. The guides asked that a couple of times while I worked at Taliesin and did the

question and answer feature.