Frank Lloyd Wright was born on June 8, 1867.

If you’re in the Wrightworld you know this.

Read my post, “Keiran don’t try to correct the internet“, about how people originally thought he was born in 1869.

In today’s post, I’m going to write about traditions within the Taliesin Fellowship connected to Wright’s birthday.

In addition to giving him a reason to have a party, Wright’s decision to celebrate his birthday with the Fellowship was cohesive.

The Fellowship was founded in 1932 in the midst of the Great Depression. So, Wright’s birthday gave the “boys” and the “girls” a celebratory purpose during the Fellowship’s hardscrabble years. After all, from 1932-35, the house for Malcolm and Nancy Willey in Minnesota was the only commission that Wright had.

In addition, Wright’s birth date, June 8, can be really nice in Wisconsin.

(and hopefully the mosquitoes aren’t in full force)

Here’s what an apprentice wrote about celebrating Wright’s birthday in 1934:

AT TALIESIN, June l4, l934

Birthday celebrations would be really celebrations if we became one year younger instead of older each time – that is, if we didn’t start too soon. We really celebrated last Friday when Mr. Wright became one year younger and said that next year he will be in his fifties. Equipped with everything possible and impossible we drove through the country to a rocky pine-covered hill and had a magnificent picnic.

From At Taliesin: Newspaper Columns by Frank Lloyd Wright and the Taliesin Fellowship, 1934-1937 (Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale and Edwardsville, Illinois, 1991), edited and with commentary by Randolph C. Henning. Page 51.

Then, in 1936, they held a scavenger hunt.

Here’s the beginning of its description:

AT TALIESIN, June 12, 1936

That the apprentices, regardless of years, should have the spirit of youth is a cardinal qualification of membership in the Fellowship. Nothing has brought that quality to the surface more than the “treasure-hunt” we held on the occasion of Mr. Wright’s birthday. While the treasure hunt lasted we were all children very young in spirit. Don’t laugh at us for being childish until you have tried the hunt yourself. You will find that you will leave most of your dignity and all of your reserve at home or lose it on the road.

By Earl Friar

From “At Taliesin” edited and with commentary by Randolph C. Henning. Page 207.

Check out the whole scavenger hunt on pages 207-210 in the “At Taliesin” book. It’s a blast that includes a live turkey gobbler!

But in 1937-38, Wright started the desert camp, Taliesin West, in Arizona.

Subsequently, celebrating his birthday became an even bigger deal.

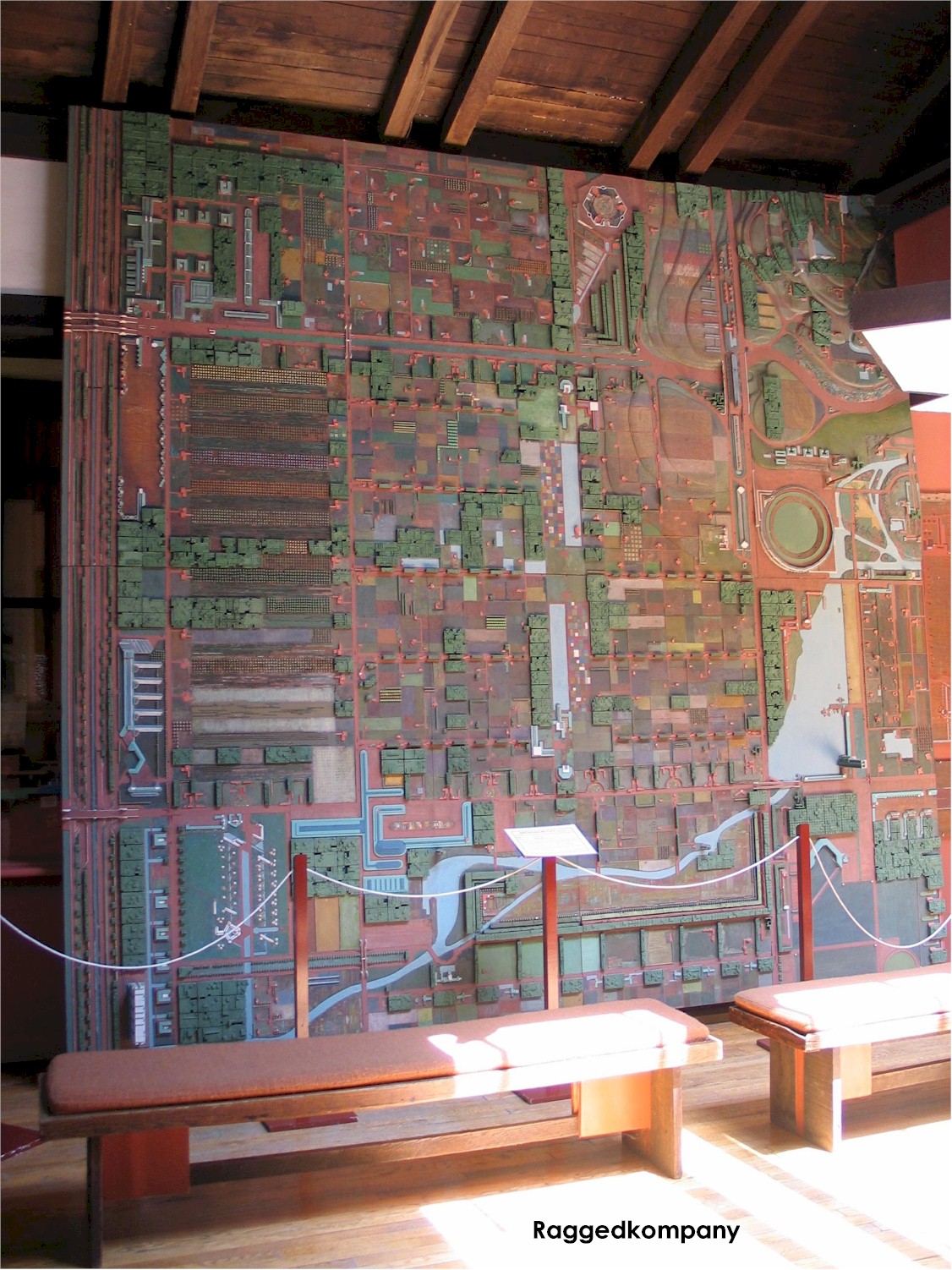

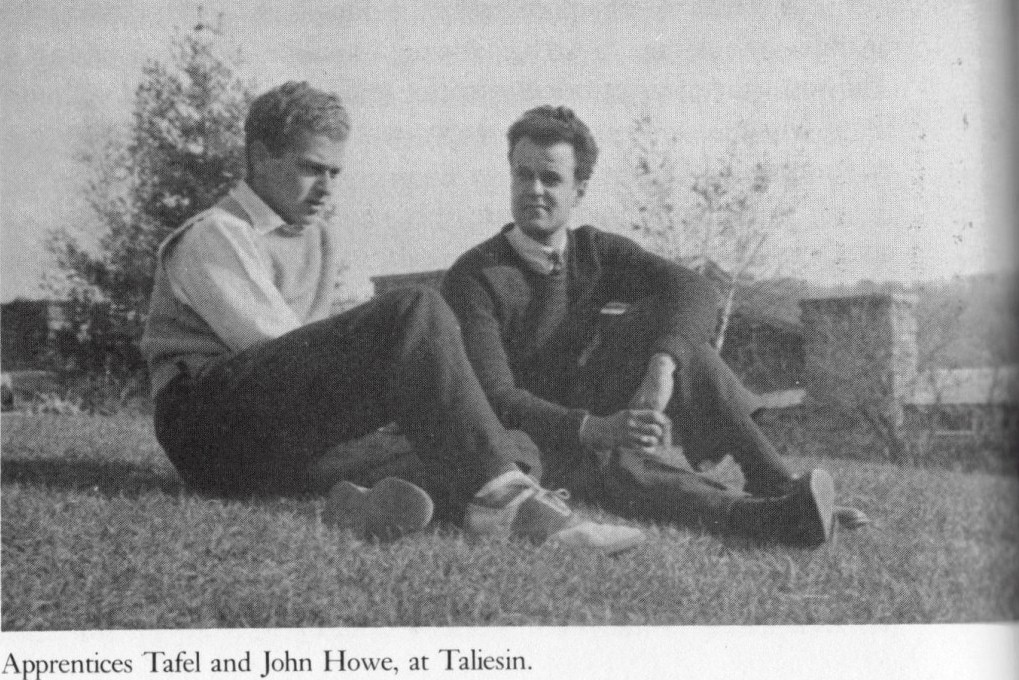

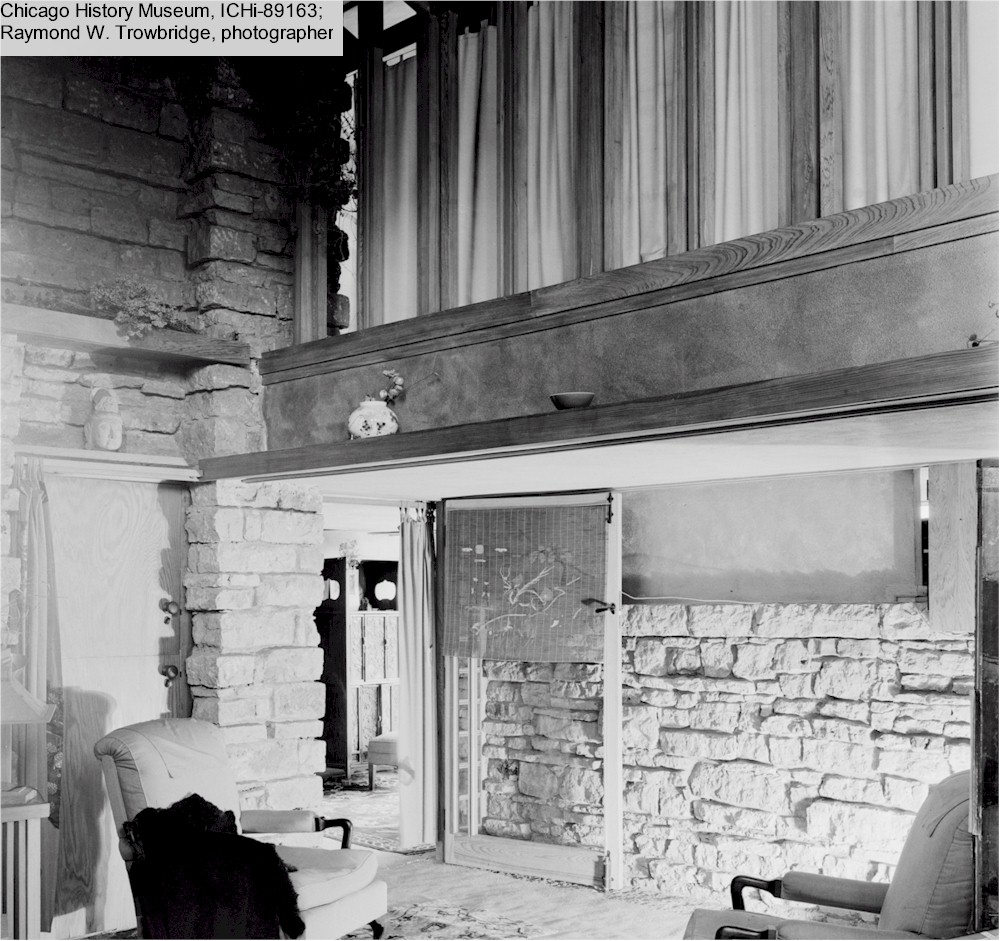

The “birthday formal” would become the first big gathering with invited guests the group could have after they had returned from the desert. Check out this photo of men and women in Taliesin’s Garden Court during Wright’s birthday formal in the 1950s:

Plus, Wright and the Fellowship knew the party wouldn’t be sullied by chilly/damp rain

or snow

Seriously—Prince was not exaggerating:

sometimes it does snow in April:

btw: I embedded this song for a chuckle about its title; not to get you depressed about a lost friend. Prince was from Minnesota and knows that sometimes it snows in April. But, seriously: since the song starts with the words, “Tracy died…” do not listen to this song if you want to remain chipper. Just be amused by Prince’s half-shirt.

And by June it’s usually warm and dry.

Time for a party!

With time, Wright’s birthday became more formal

Check out my photo below of all the fancy people:

I took this photograph in Taliesin’s Garden Court during Wright’s birthday formal in 2019. If I’d been thinking, you would see a photo of me in my fancy dress, too.

In addition, Wright’s birthday became the time for one of the year’s

Box Project presentations.

The Box Projects were really important for the Taliesin Fellowship as a learning institution.

Olgivanna Lloyd Wright, Wright’s wife, explained the Box Projects well:

The Box is a tradition in the Fellowship, occurring twice a year, at Christmas and at the birthday. It consists of designs by the young people, plans, abstractions, models, paintings, weaving and ceramics….

After giving Wright their projects as Olgivanna explained:

Each one explains that he has done and Frank gives him the benefit of his criticism, indicating to him the direction he should take….

The Life of Olgivanna Lloyd Wright: From Crna Cora to Taliesin; from Black Mountain to Shining Brow, compiled and edited by Maxine Fawcett-Yeske, Ph.D. and Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, D.H.L. (ORO Editions, 2017), 186.

Therefore, the Box Projects allowed Wright to check on the development of the work by apprentices.

Everyone did a project—

even the spouses of apprentices.

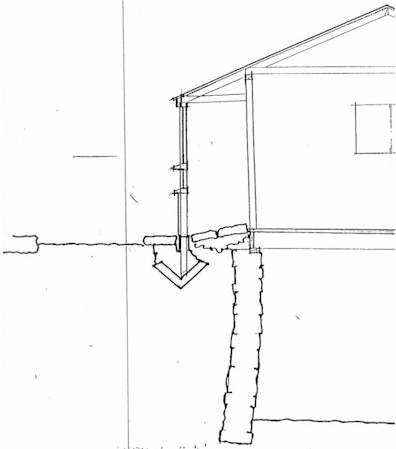

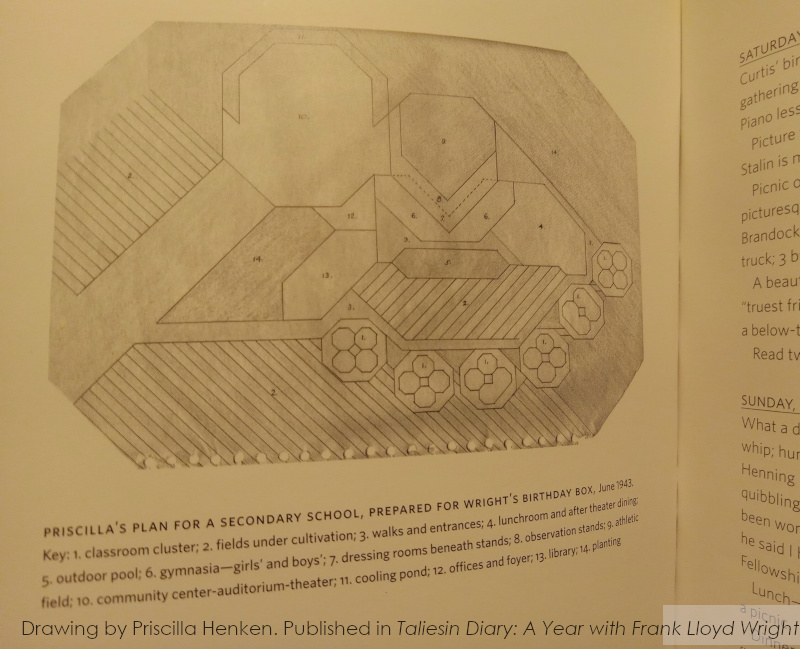

During Wright’s birthday Box in 1943, Priscilla Henken (the wife of apprentice/architect David Henken) gave a floor plan for a school (even though she wasn’t a draftsmen). I got a photo of the plan from her published diary:

This drawing was published on page 176 of Taliesin Diary: A Year with Frank Lloyd Wright, by Priscilla Henken (W.W. Norton & Co., New York, London, 2012).

Moreover, Priscilla noted some very nice things that Wright said about her drawing:

About my plans, which FL looked at after tea, he said that I had a lot of common sense, that I took the school as it was ![]() made an extraordinarily good thing out of it; that I had a lot of brains under this hair of mine; that now he knew I was busy during a lot of the time he couldn’t account for me; that I was the surprise… package of the box.

made an extraordinarily good thing out of it; that I had a lot of brains under this hair of mine; that now he knew I was busy during a lot of the time he couldn’t account for me; that I was the surprise… package of the box.

Taliesin Diary: A Year with Frank Lloyd Wright, by Priscilla Henken, 175.

The Box Projects and Wright’s birthday celebration are an interesting way to mark how Frank and Olgivanna Lloyd Wright created the culture of the Taliesin Fellowship.

Culture:

The CliffNotes website gives a good definition of it under “Sociology“. Culture, it says:

consists of the beliefs, behaviors, objects, and other characteristics common to the members of a particular group or society. Through culture, people and groups define themselves, conform to society’s shared values, and contribute to society. Thus, culture includes many societal aspects: language, customs, values, norms, mores, rules, tools, technologies, products, organizations, and institutions.

In 1994 when I started in tours, the Fellowship still had the Box Project presentations around Wright’s birthday. But that was changed in the mid-late 1990s. The reason for that was the difficulty apprentices had with moving from Arizona in the midst of their preparation for “the Birthday Box”. Consequently, they switched the presentation to September. That way, they could spend all summer working on it. And didn’t have to drive all that way from Arizona on little sleep, or worry about smashing the models or losing the computer files in the migration.1

First published on June 3, 2023.

The photograph at the top of this page was taken for The Capital Times in Madison for Wright’s birthday in 1957.

Note:

1. They changed the Box Presentation in Arizona, I think, to March or April.