August 15, this coming Thursday, marks 110 years since 7 people were inexplicably murdered at Frank Lloyd Wright’s home, Taliesin, by his servant, Julian Carlton.

I’ve written about it a couple of times1 and had not planned on writing anything today.

But I’ve gathered a lot of information over the years and,

in the spirit of “preservation by distribution“,

I decided to put up a post with the statements by the survivors, or related parties, that appeared in the newspapers.

I think this is kosher, since I’m publishing news that was written 110 years ago.

Just so you know, sometimes the stories spell Julian’s last name as “Carleton” and I decided to keep those misspellings without correcting them; writing “[sic]” after each misspelling gets distracting. Additionally, one story refers to Wright’s partner, Mamah Borthwick, as “Mrs. Borthwick”.

Herbert Fritz’s narrative of what happened

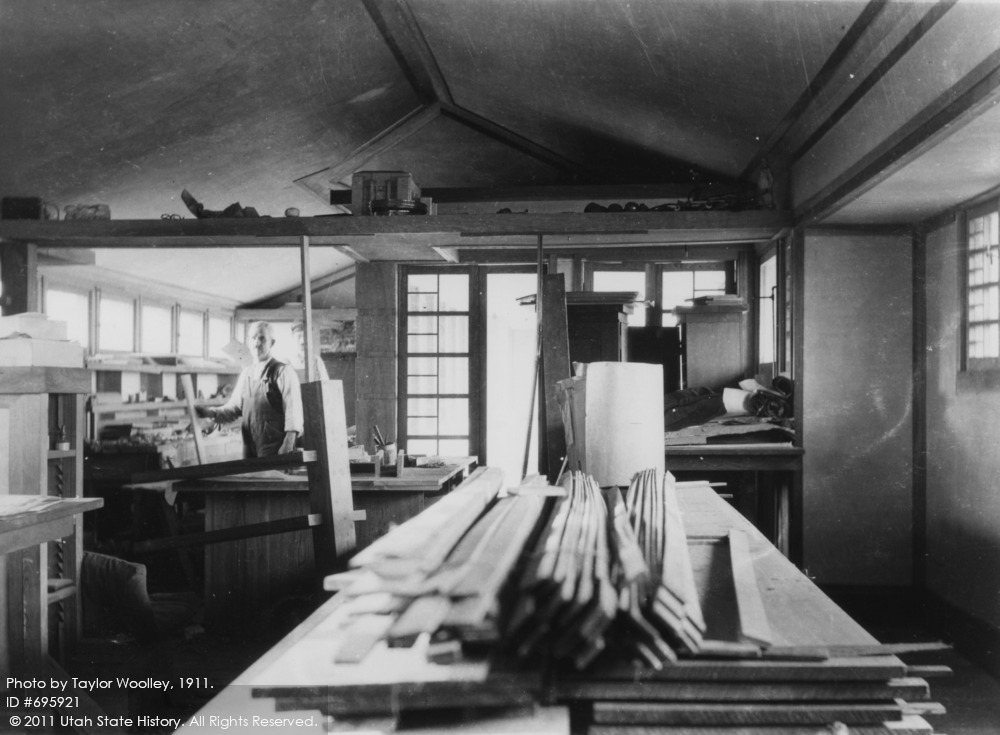

He was one of Wright’s draftsmen. He survived by jumping out of a window when he noticed the fire, but before Carlton could attack. As a result of his relative lack of injuries (he broke his arm), Fritz gave the most complete description of what happened.

This first appeared in the The Chicago Daily Tribune on August 16, 1914:

Story of Survivor.

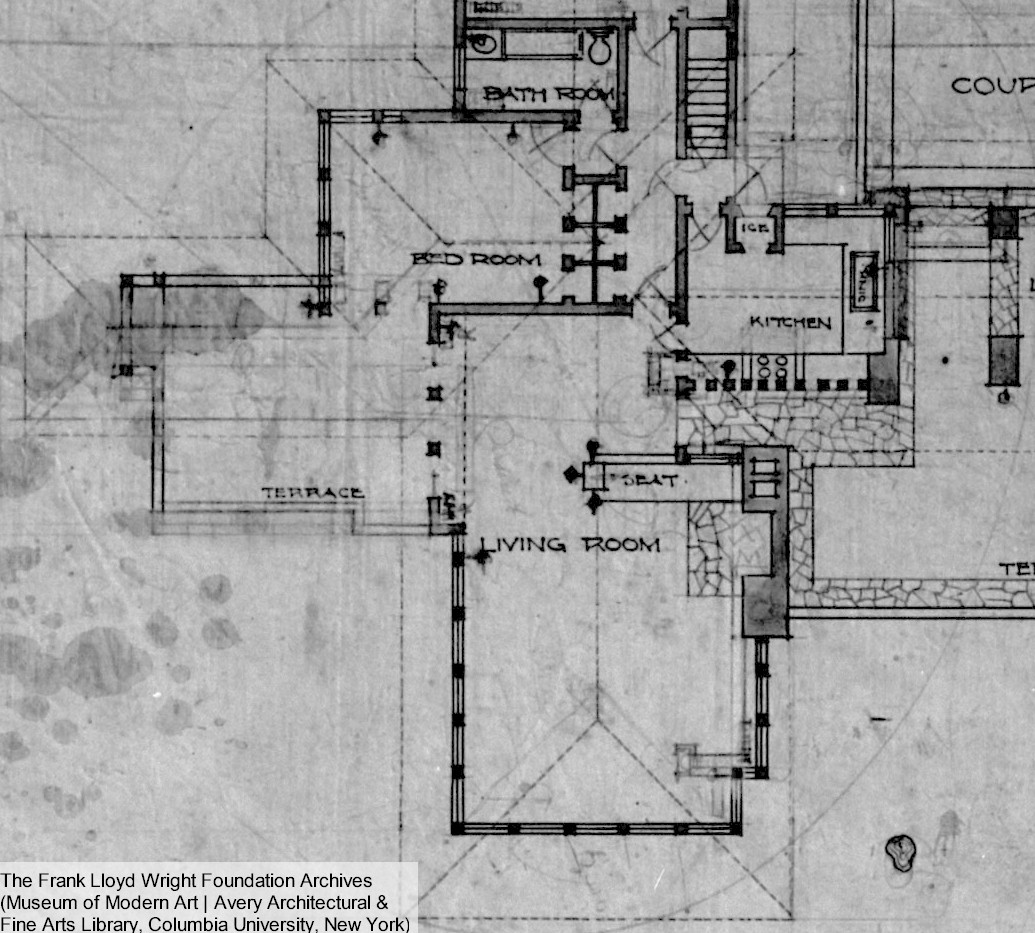

“I was eating in the small dining room off the kitchen with the other men,” said Fritz. “The room, I should say, was about 12 x 12 feet in size. There were two doors, one leading to the kitchen and the other opening into the court. We had just been served by Carleton and he had left the room when we noticed something flowing under the screen door from the court. We thought it was nothing but soap suds spilled outside.

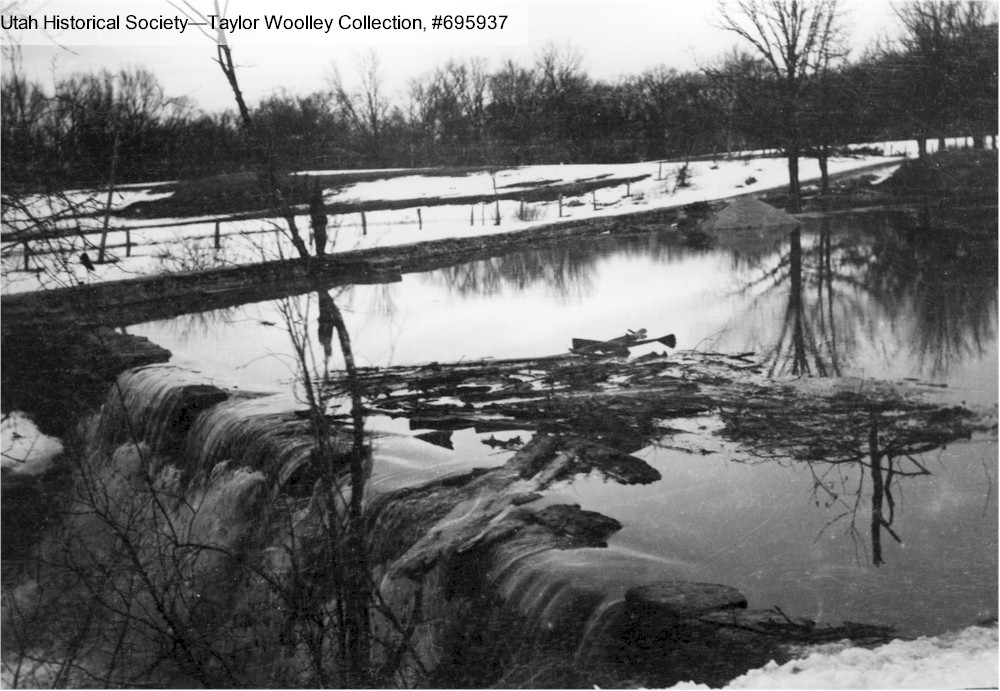

“The liquid ran under my chair and I noticed the odor of gasoline. Just as I was about to remark the fact a streak of flame shot under my chair, and it looked like the whole side of the room was on fire. All of us jumped up, and I first noticed that my clothing was on fire. The window was nearer to me than the other door and so I jumped through it, intending to run down the hill to the creek and roll in it.

“It may be that the other door was locked. I don’t know. I didn’t think to try it. My first thought was to save myself. The window was only about a half a foot from the floor and three feet wide and it was the quickest way out.

Arm Broken by Fall.

“I plunged through and landed on the rocks outside. My arm was broken by the fall and the flames had eaten through my clothing and were burning me. I rolled over and over down the hill toward the creek, but stopped about half way. The fire on my clothes was out by that time and I scrambled to my feet and was about

Cont’d, p. 6 column 1

to start back up the hill when I saw Carleton come running around the house with the hatchet in his hand and strike Brodelle, who had followed me through the window.

“Then I saw Carleton run back around the house, and I followed in time to see him striking at the others as they came through the door into the court. He evidently had expected us to come out that way first and was waiting there, but ran around to the side in which the window was located when he saw me and Brodelle jump out.

“I didn’t see which way Carlton went. My arm was paining me, and I was suffering terribly from the burns, and I supposed I must have lost consciousness for a few moments. I remember staggering around the corner of the house and seeing Carleton striking at the other men as they came through the door, and when I looked again the negro was gone.”

Statement by William Weston in The Detroit Tribune on August 16:

Weston was Wright’s carpenter. He followed Fritz and another victim, Emil Brodelle, out of the window. Carlton gave him a glancing blow, so he survived. However, Carlton did murder Weston’s 13-year-old son Ernest. Ernest and two others (David Lindblom and Thomas Brunker) were attacked exiting through the door on the opposite side of the room:

“As each one put his head out,” said Weston, “the negro struck, killing or stunning his victim. I was the last. The ax struck me in the neck and knocked me down and I guess he thought he had me, because he ran back to the window and I got up and ran. When I looked back, the negro had disappeared.[“]

Unfortunately, that’s it. Although he was probably not able to talk since his son died later on the 15th.

Gertrude Carlton quoted in the Escanaba Daily Press on August 18:

Authorities found Gertrude Carlton, Julian Carlton’s wife, innocent of any involvement in the crime. Two weeks later, she was allowed to leave. She took a train to Chicago and was never heard from again.

“I don’t know why Julian did it,” she said. “He must have been crazy. I think he was. He had just served dinner, and I saw him cleaning a white rug in a pan of gasoline out in the courtway. He had his pipe in his mouth, and I saw him light a match.

“The next thing I knew the kitchen was in flames, and I saw Julian running toward the barn with a hatchet in his hand. I ran downstairs to the cellar and climbed from a window.”

The woman was arrested while walking on the road to town. She said her husband had been moody and “acting queer” of late.

“I woke up several times at night and found him sitting up,” she declared. “I would ask him what was the matter and he would say that workmen around the place were trying to ‘do’ him. That was why he made me tell Mrs. Borthwick we would leave Saturday because it was lonely for me in the country.”

Wright was in Chicago,

finishing up his Midway Gardens commission when he found out about the fire. Here’s the Chicago Tribune again on Aug. 16:

Tells of Crime.

Mr. Wright was notified of the tragedy at his office in the Orchestra building by long distance telephone.

Mr. Wright almost collapsed when the news first reached him. He got the tragic long distance telephone message while at Midway Gardens, the new south side amusement park, which he designed.

“This is Frank Roth at Madison,” came a voice over the wire. “Be prepared for a shock. Your wife—that is, Mrs. Cheney—the two children, and one of your draftsmen have been killed by Carleton.

“Carleton set fire to the bungalow and got away. He must have gone crazy. A posse is chasing him. You’d better get to Spring Green right away.”

Roth, from whom the message came, is a friend of the architect.

Subsequently Wright received a telegram from Spring Lake signed with the initials of Mrs. Cheney—of Mamah Borthwick, or as she now calls herself

“Come as fast as possible; serious trouble,” was her message.

“Frank Roth” is an unknown person and no one has found the telegram. “Spring Lake” is wrong. It should be Spring Green.

Here’s the Chicago Tribune on Wright’s statements before he came back to Wisconsin on the train with his son, John:

Unable to Talk Coherently.

The architect was so distraught he could not tell a coherent story to the detectives.

“The Carletons, Julian and his wife, were the best servants I have ever seen,” he said. “The wife cooked and Julian was a general handyman. They were Cuban negroes, and Julian especially seemed to have an intelligence above the average and a good education for one of his class.

“They had not been engaged permanently and were to have quit our employ today. Julian was to have started for Chicago on the 7:45 train this morning. The train would have reached the city shortly after 1 o’clock, and he was to have visited my office to get his wages.

“Three days ago, when I last saw him, he seemed perfectly normal. He must have lost his mind—and yet I cannot believe that the news is true. The fact that the telegram was signed M.B.B. was received after the alleged murders buoys my hopes.”

Paul Hendrickson did some good work to show that Julian Carlton was not from Cuba or Barbados, which was repeated in other newspaper stories at that time. In his book, Plagued by Fire, Hendrickson makes the case that Carlton was from Alabama.

First published August 13, 2024.

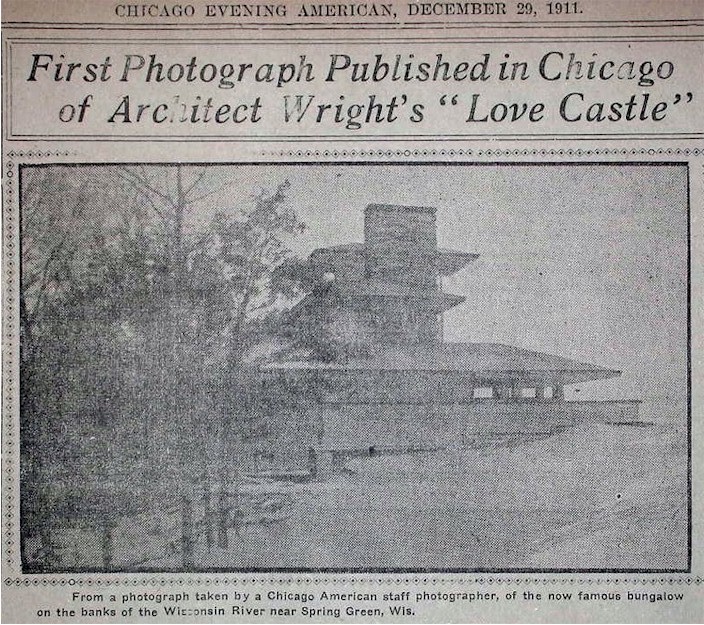

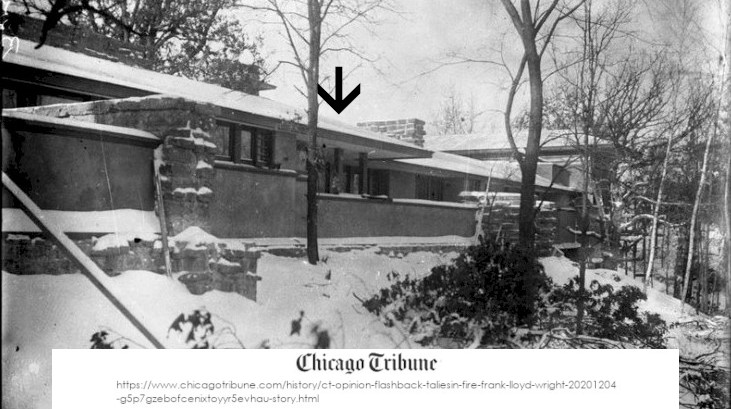

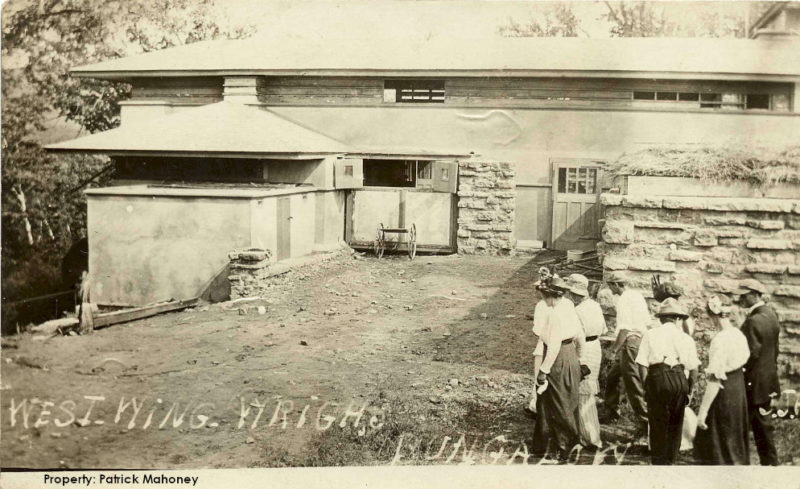

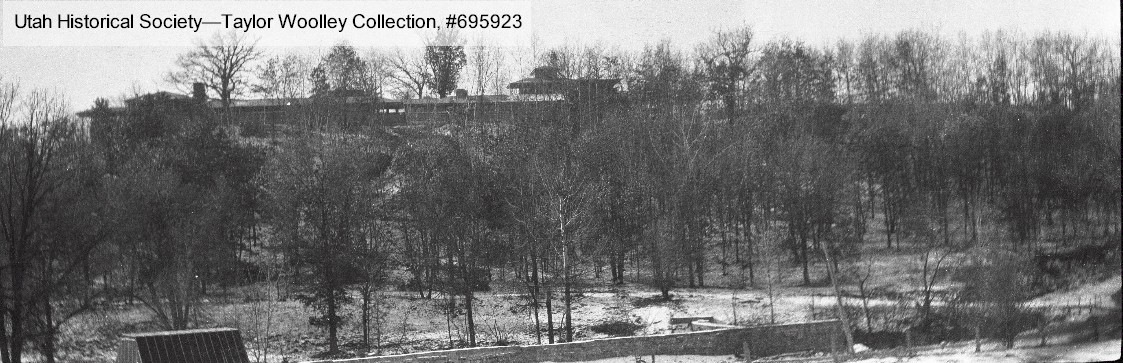

A.S. Rockwell took the photograph at the top of this post on the day of, or the day after, the fire. The photograph in on Wikimedia Commons and is in the public domain. See here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Taliesin_After_Fire.jpg for information about the origin of the photograph.

Note:

1. if only to tell you that Carlton didn’t serve his victims soup!

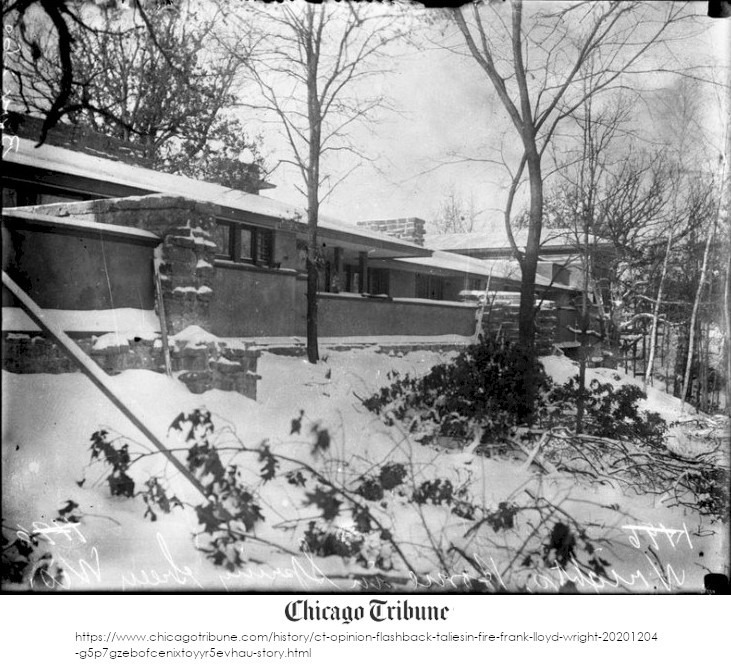

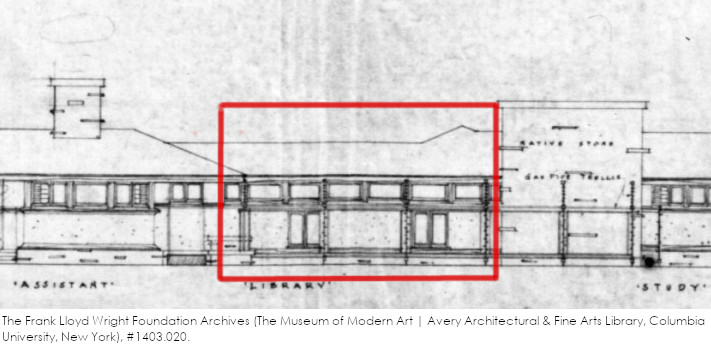

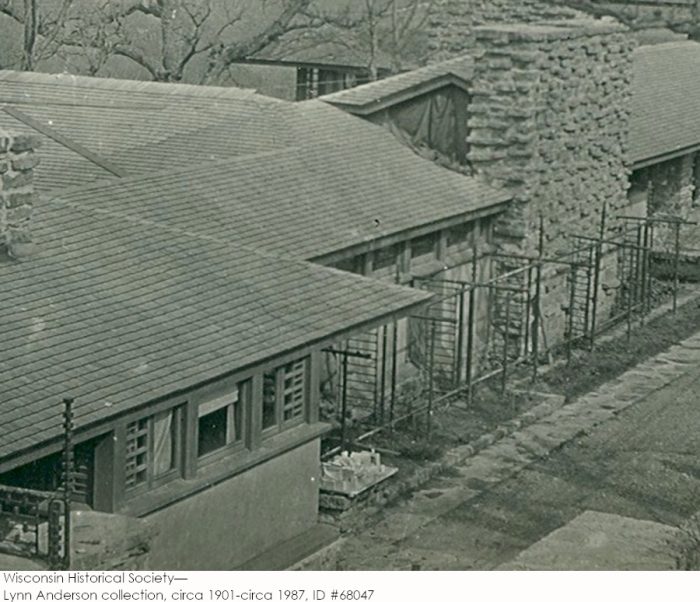

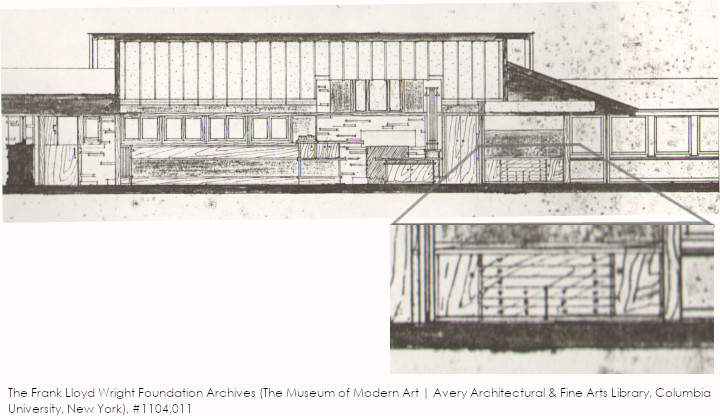

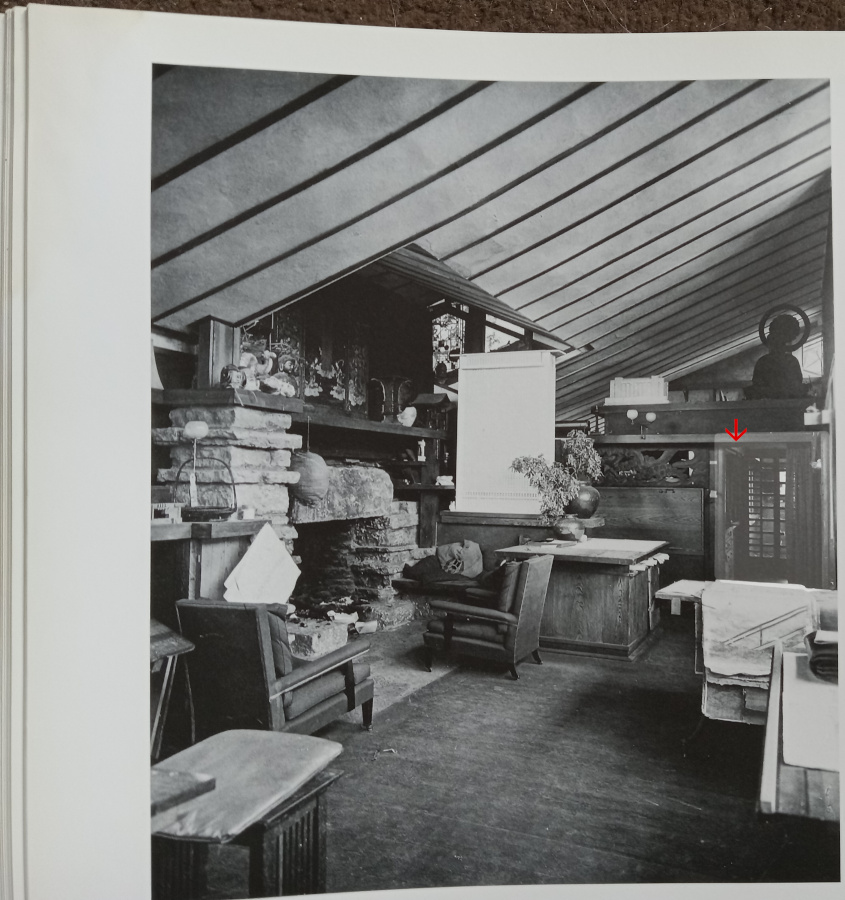

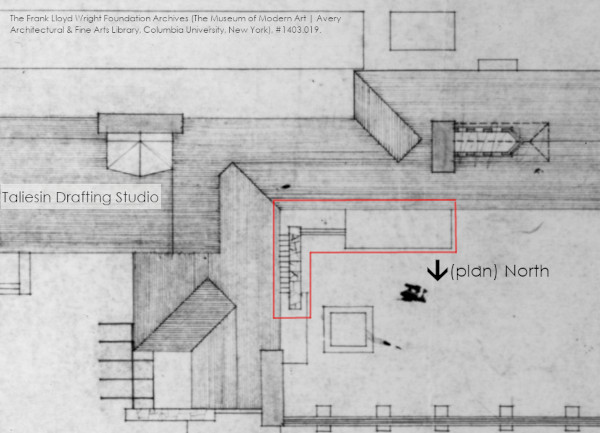

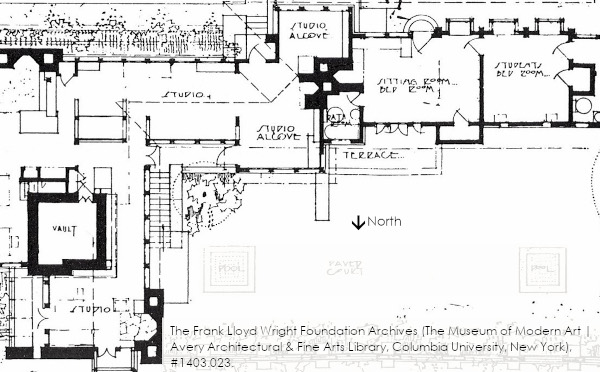

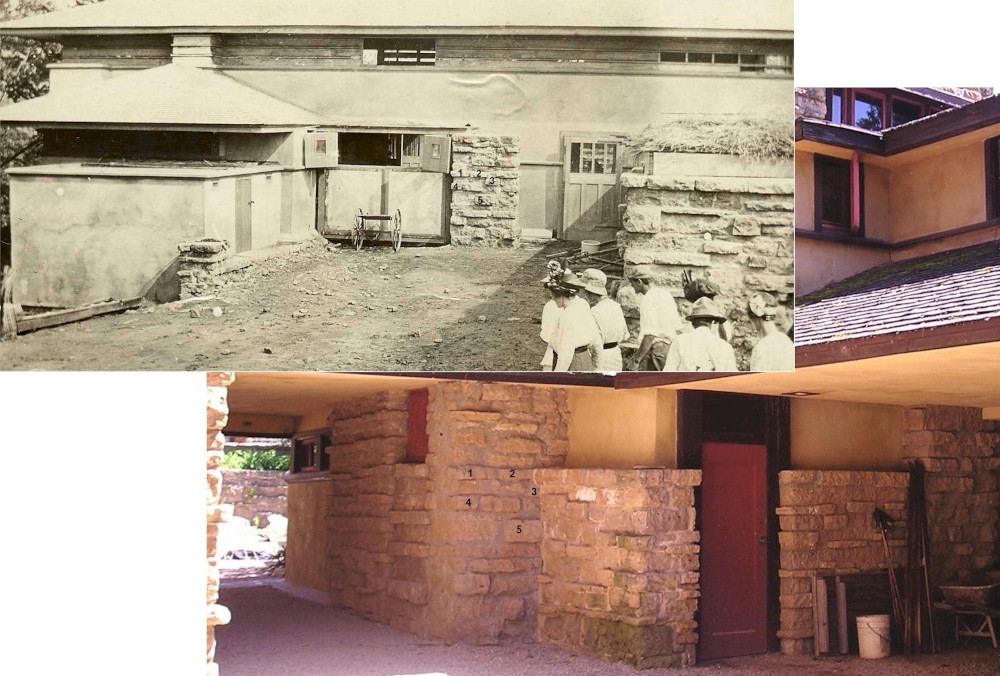

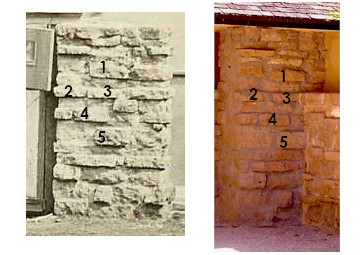

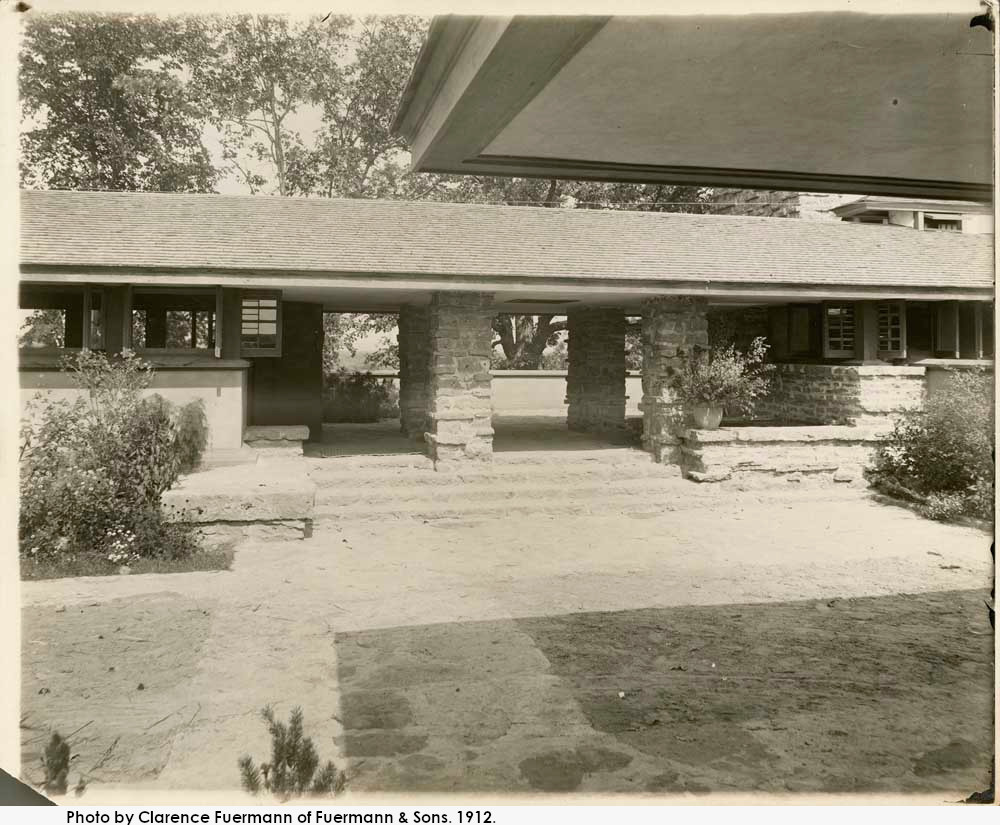

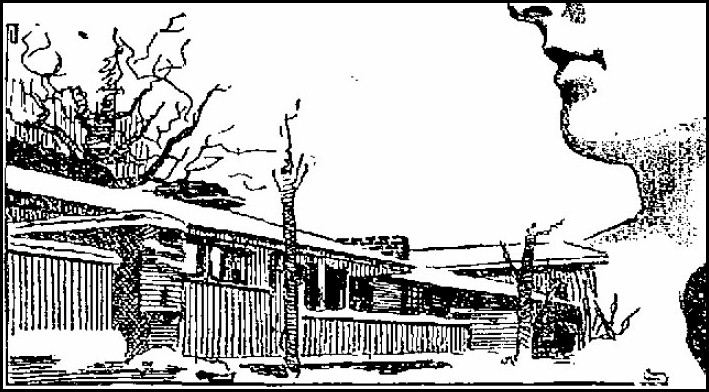

You walk up the steps at Taliesin to Wright’s studio at Taliesin (the north wall of the studio is to the right). The parapet from the Taliesin I photo ended at the stone that is to the left of the tree trunk (the tree trunk is to the left of the window that’s on the extreme right in the photograph) .

You walk up the steps at Taliesin to Wright’s studio at Taliesin (the north wall of the studio is to the right). The parapet from the Taliesin I photo ended at the stone that is to the left of the tree trunk (the tree trunk is to the left of the window that’s on the extreme right in the photograph) .