Curtis Besinger is seated at the piano on the far left conducting choir practice. This photograph was taken 1940-42 inside the room at Taliesin West known as the Kiva. See the list of apprentices at the bottom of this page.

It’s been awhile since I’ve recommended something new for you to read.

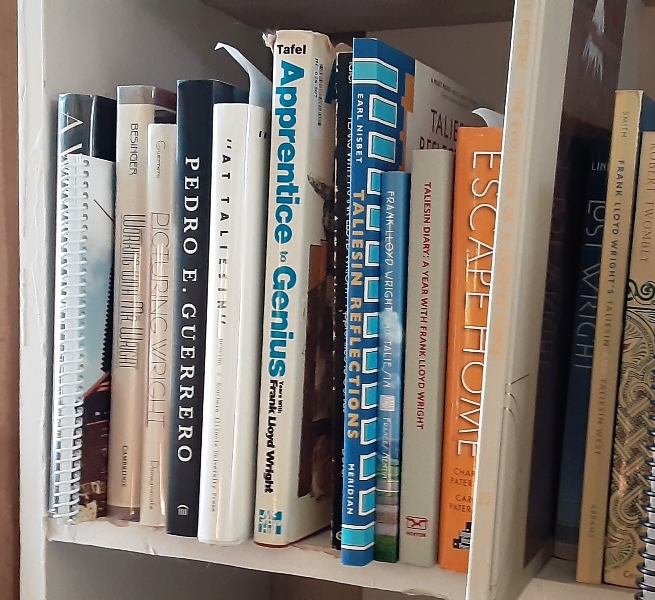

I wish there were more books available from former Taliesin Fellowship apprentices, but we’ve got what we’ve got.

So

I’m writing in this post about one of the great books about the Fellowship: Working With Mr. Wright: What It Was Like by Curtis Besinger. It was released in 1995.

The book link above takes you to the listing at Abebooks.com. You can get most copies for a good price in either hard- or softcover.

Besinger came to the Fellowship in 1939 and

(except for times on projects on in jail during World War II)

stayed until 1955.

He worked on it for years,

and got assistance on his remembrance of things from another former apprentice, John Geiger.

Besinger’s book is a nice counterpoint to Edgar Tafel’s Apprentice to Genius.

Tafel jumps in and out of a straightforward narrative in his book about his time in the Fellowship; while doing so, he tells you all about Wright, his philosophy, and his career.

On the other hand, Besinger sticks to a main chronology of just his time there. He approaches it mostly on a season-by-season basis. By doing this, he gives you information on what was going on at that time at Taliesin in Wisconsin and Taliesin West in Arizona.

In addition,

his book has chapters concentrating on Music and Movies in the Fellowship

In fact, the photo of apprentices at the top of this post, showing them practicing chorus, is on page 134 in the “Music” chapter in Besinger’s book

and how things went related to World War II. He also wrote a lot on what led to his decision to leave.

One interesting thing, too, is that he mentions the group-perception of the husband-and-wife couple, Prisilla and David Henken.

Then in 2012, A Taliesin Diary: A Year With Frank Lloyd Wright came out. This book contained the diary entries that Priscilla wrote while she and David were in the Fellowship in 1942-43. Besinger’s understanding rounded out what Priscilla felt while in the group.

The incredible thing

about Besinger’s book is that it elevated the understanding of Taliesin’s history and what impact the apprentices had on it.

For instance,

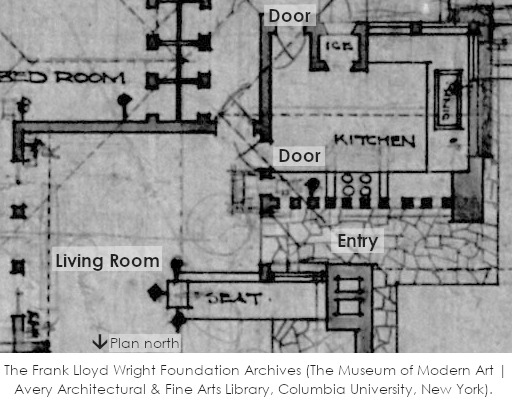

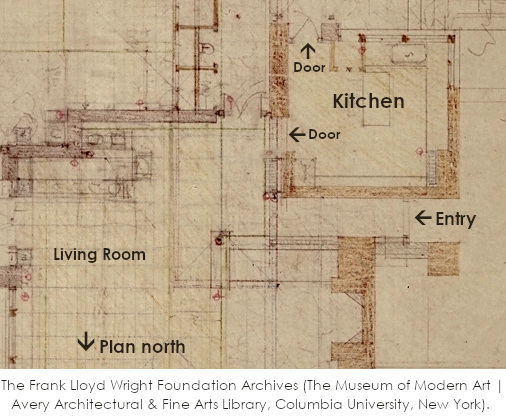

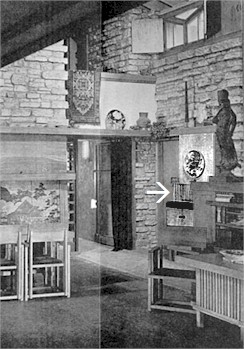

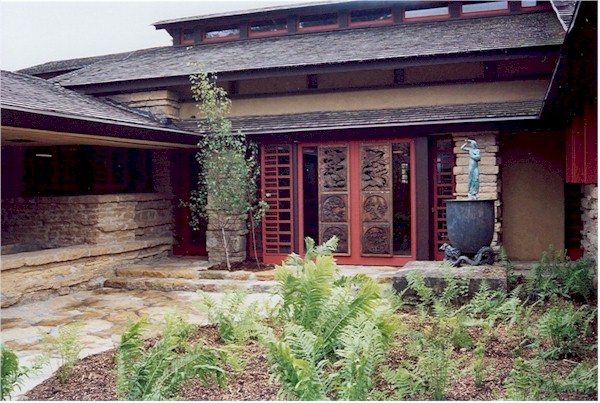

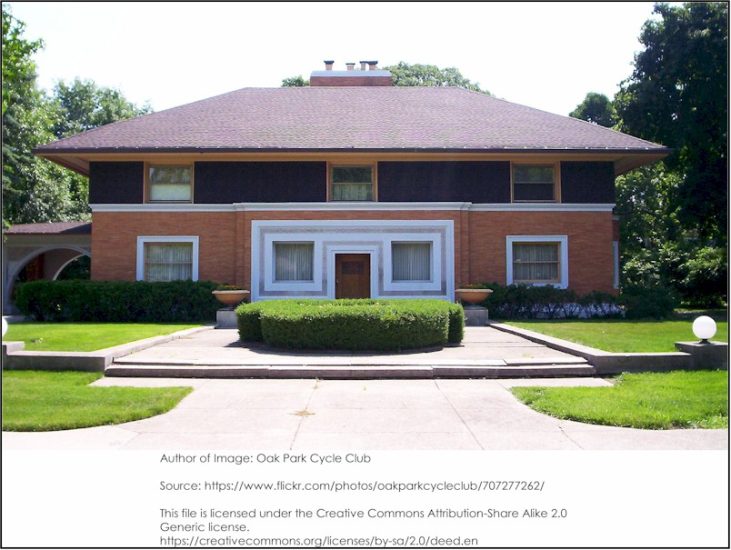

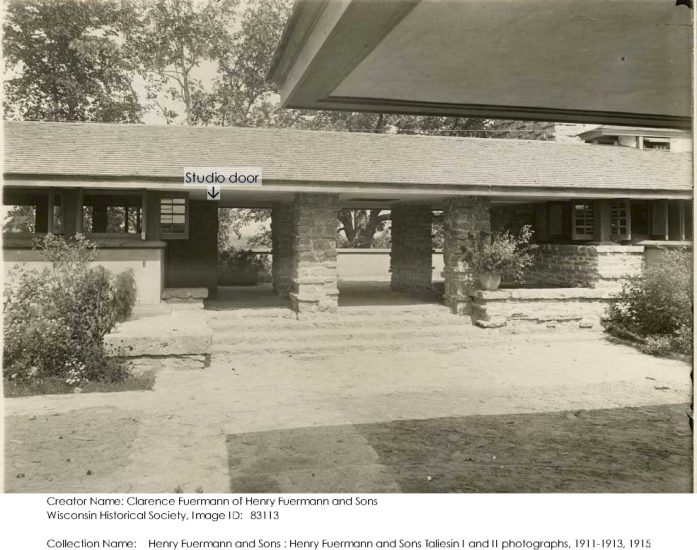

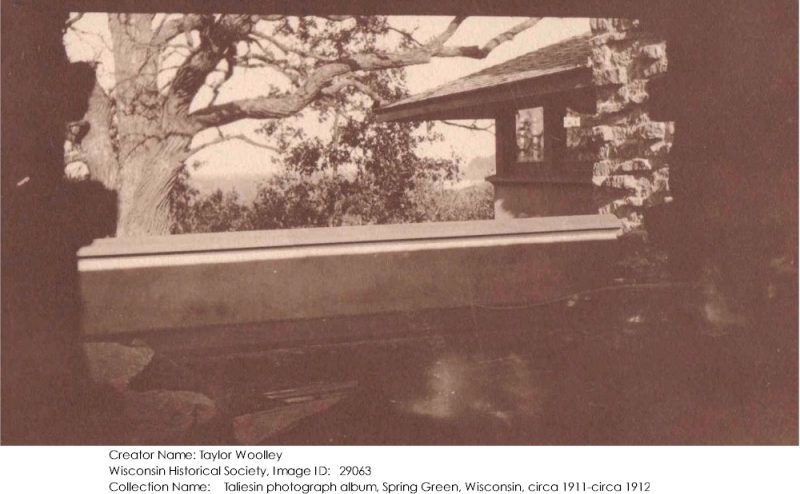

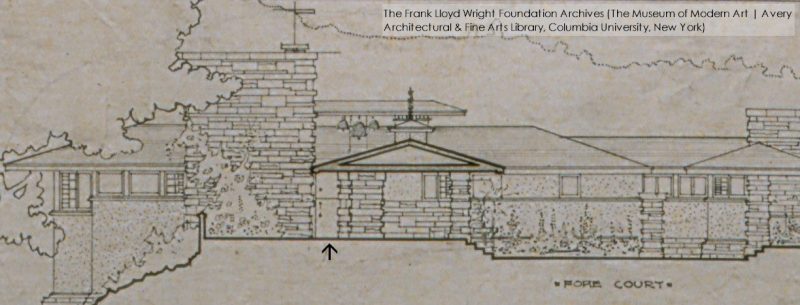

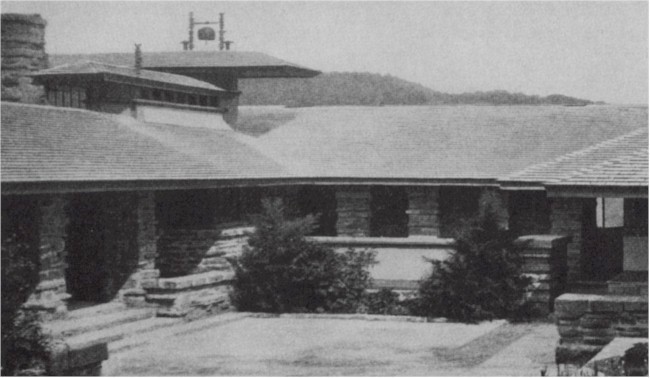

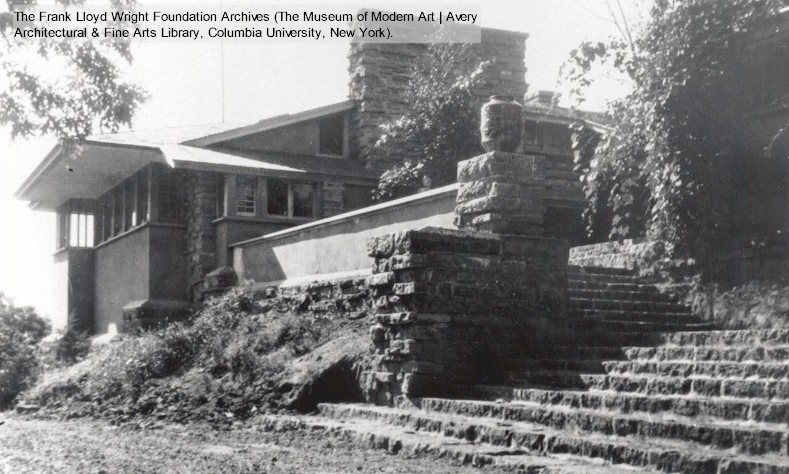

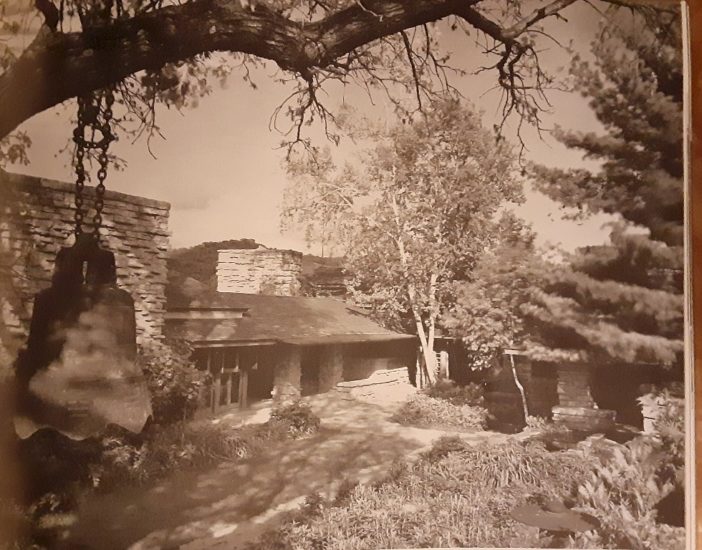

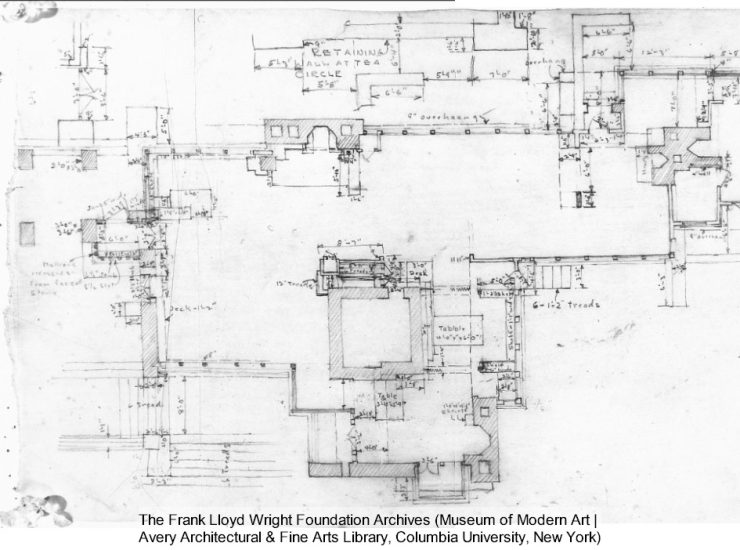

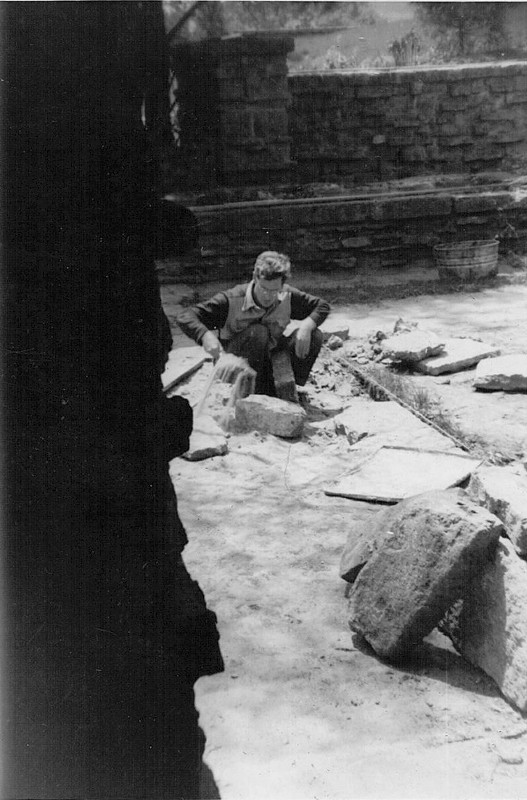

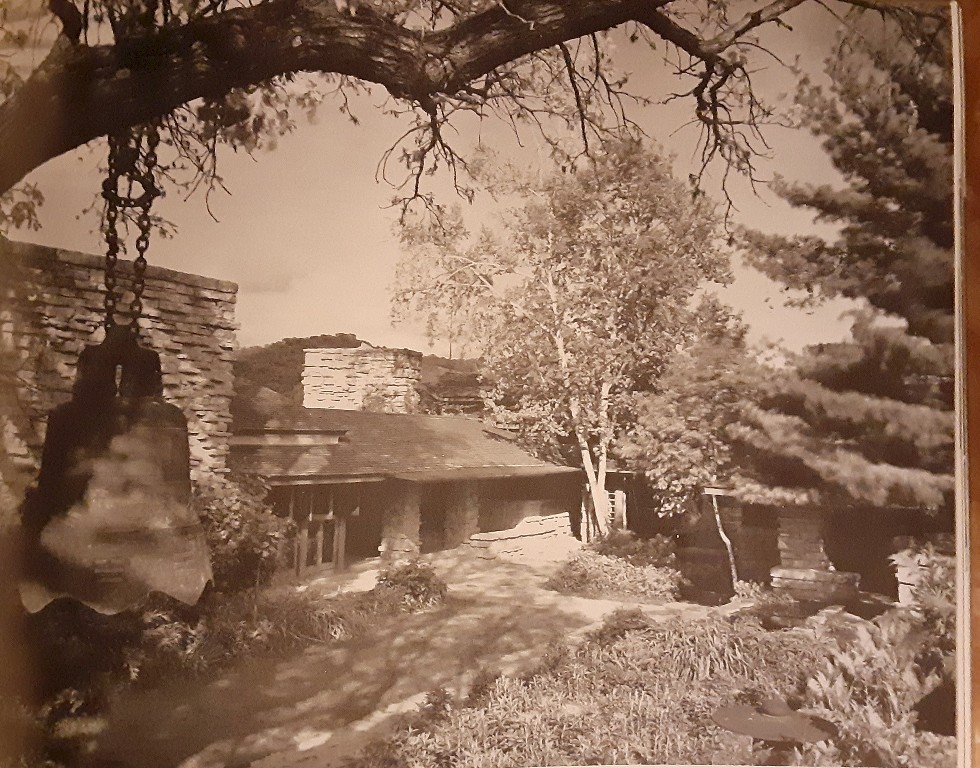

he wrote about the creation of the “Garden Room” at Taliesin.

I’ve got an exterior photo of it at the top of this post, and an interior photo in this post.

I’d hear the Garden Room was originally Taliesin’s Porte-cochere, but I didn’t know the exact year of this change.

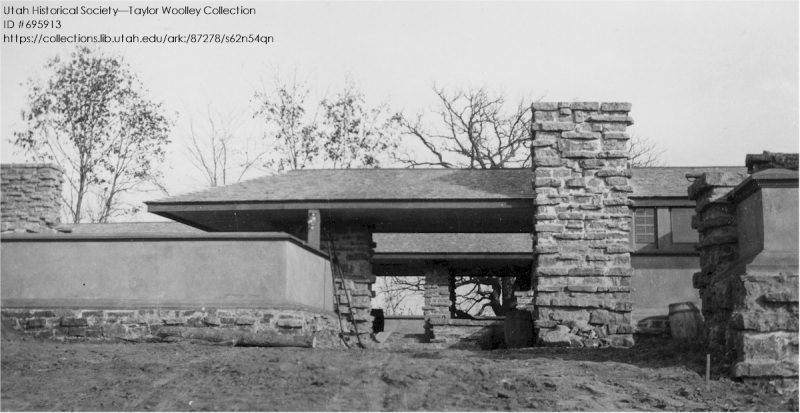

Besinger explained the Garden Room construction along with almost everything done at Taliesin in the summer of 1943. Besinger wrote that it was linked to Wright’s anticipation of getting the commission for the Guggenheim Museum.

Wright did so many things (about 5 or 6 things) that I often said on tour that Wright wanted’ to “spruce up” Taliesin in order to get the job.

Later I learned that these changes he made in stone were due to his acquiring it in 1942 “In Return For the Use of the Tractor“

While I thought Besinger linked the Garden Room directly to Wright wanting the Guggenheim commission:

He began a process that later in the summer turned into preparation for an anticipated visit by Solomon Guggenheim and … Baroness Hilla von Rebay. They were coming to discuss the building of a museum to house Mr. Guggenheim’s collection of nonobjective art.

Curtis Besinger. Working with Mr. Wright: What It Was Like (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, 1995), 146.

But I was wrong.

When the Taliesin Diary came out, I found out that Wright didn’t make changes to Taliesin in order to convince Guggenheim to hire him as an architect. No—Priscilla Henken was writing in the summer of 1943 that Wright went to NYC and signed the contract for the commission before he was really making changes at the house.

So, I was wrong, sorta.

Additionally,

Besinger’s book contains information about:

- when the former Fellowship dining room at Taliesin got its clerestory

- the movement of the main kitchen for the Fellowship to Hillside

- the beginning of the construction of the Hillside Theater Foyer in the late 1940s

- the expansion of Wright’s bedroom in 1950

- how the Fellowship reacted after the untimely death of Svetlana Peters

- Wright’s reaction upon the breaking of a vase at Taliesin.

- …. And others

I’ll print Wright’s reaction to the broken vase here

I liked using this story on tours from the “Summer 1948” chapter in Besinger’s book:

“One afternoon, during tea in the tea circle, Tal and Brandoch1 were playing and romping about the Hill Garden nearby. During their romping they knocked over a large Ming tea jar… standing on the … stone outcrop in the garden. The jar rolled down the hill, … and … shattered into hundreds of pieces…. There was a silent moment of suspense and an expectation that Mr. Wright would be angry. Instead he appeared to accept this philosophically as one of the hazards of living with works of art and, particularly, with small boys.”

Curtis Besinger. Working with Mr. Wright: What It Was Like (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, 1995), 192-3.

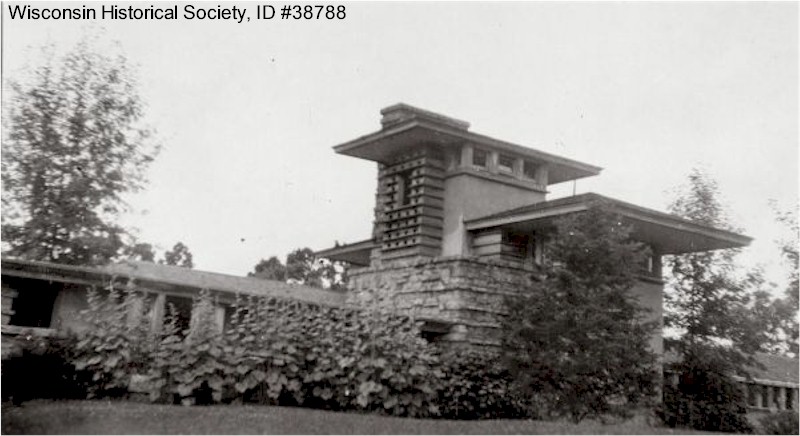

Just so you know, that vase is not the vase you see on Taliesin’s Hill Crown or at the top of the steps on House and Estate tours before you go inside the Taliesin studio. That’s the vase you see today in the photo below on the left:

Maynard Parker took this photograph in 1955.

You saw this in my post “The Abandoned Stairway at Taliesin“

No, I believe that post is the one that I have a photograph of, below:

The photograph shows it where it was when I started: on the edge of the empty pool at Taliesin’s little kitchen. I was told at one point that Fellowship member, Ling Po, glued it back together.

After a few tour seasons, the Preservation Crew realized that having this glued-together vase outside was probably not a good idea. So they put it (as I was told) “into intensive care” in a box. I’m sure the collections manager in Wisconsin for the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation knows its current state and location.

Originally published February 16, 2025.

I got the photo at the top of this post from Working With Mr. Wright, p. 134. Besinger thanks Robert C. May for the image.

Besinger identified most of the men in the photo, so I’ll do that, too (“Preservation by Distribution“, you know):

Front row, left to right: seated: Besinger conducting at the piano, Wes Peters, Davy Davison, Aaron Green, Cary Caraway. Standing: Gene Masselink, John Hill. Stacked behind Wes: Jack Howe, Lock Crane, Marcus Weston. Behind Gordon Lee are Jim Charlton and Normal Hill, unknown, Gordon Chadwick, Chi Ngia Show, Bob Mosher, and Kenn Lockhart.

Note:

- “Tal” was Tal Davison, born to Fellowship members Kay and Davy Davison; and “Brandoch” was Brandoch Peters, the oldest son of Wes and Svetlana Peters.