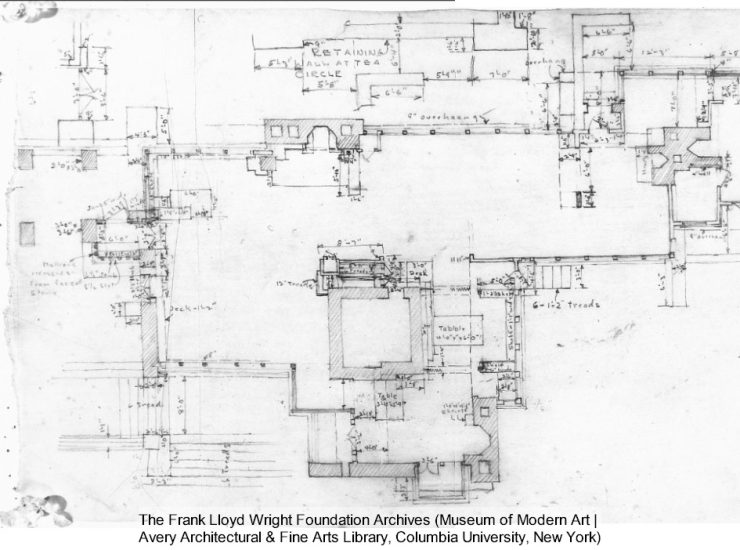

The drawing above shows the main floor of Taliesin where Wright lived, 1936-39. This is one of my favorite Taliesin drawings. Why? Because it actually shows the space pretty much as it existed at that time.

In this case, I’m talking about Taliesin the building, not Taliesin the estate.

I mean: the UNESCO site, not the 600-acre National Historic Landmark1

I wanted to write about that after putting up the link to a post on my LinkedIn page.

While doing that I re-read that I told you all I should “write about” my Taliesin Chronologies some time.

This was great, because

since I don’t answer “Hey Keiran” questions from Taliesin tour guides anymore,

I was looking for something new to write.

The compact version of the Chronology project is in my post, “How I Became the Historian for Taliesin“.

The longer version

involves

as I recall,

some tears and some hyperventilation.

Over 21 years ago, Taliesin Preservation (then doing Taliesin’s restoration2) was gearing up for the Save America’s Treasures project that put in comprehensive drainage at the residence in 2003-04

(that’s when we found the window).

So, in the summer of 2003 I was asked to start writing detailed histories of each space in Wright’s living quarters.

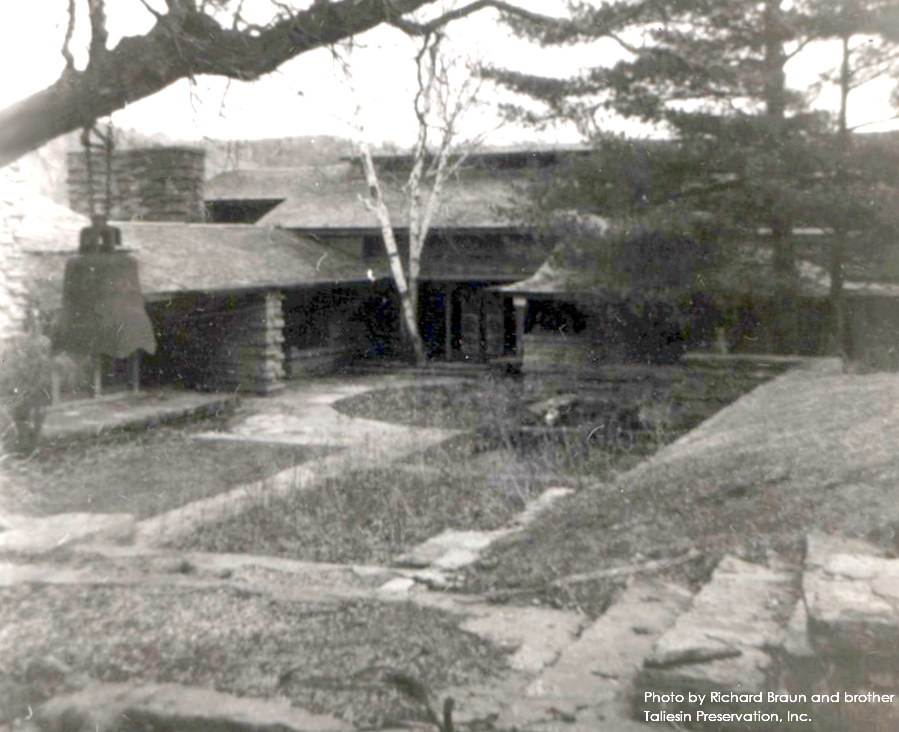

You see it in most of the photo below:

Property: Taliesin Preservation, Inc.

I concluded it was best for me to tackle Taliesin one room at a time.

Because I did not intend to write a detailed explanation of what we knew about the entire floor where Wright lived after he started his home,

And then

after 56 pages or so,

write

So, in the next year….

Repeat, repeat, repeat until you got to the year 1959…

My analysis began at the southern part of this floor, with the intention of writing a history of each room to the north.

I chose this path because there were generally fewer post-1925 changes made to this wing as you go north (towards Taliesin’s living room).

I researched and wrote the complete history

Or at least I hope I did

of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Bedroom and bedroom area over about 6 weeks.

I mean,

As I’ve written before, the man often didn’t write what he was doing at his house in any detail.

Or sometimes he wrote some things that we don’t necessarily find out to be true.

Like, he wrote in his autobiography that after Taliesin’s 1925 fire,

I made forty sheets of pencil studies for the building of Taliesin III.3

An Autobiography in Frank Lloyd Wright Collected Writings: 1930-32, volume 2. Edited by Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, introduction by Kenneth Frampton (Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., New York City, 1992), 303.

40 sheets? Where the hell are the 40 sheets, Frank?

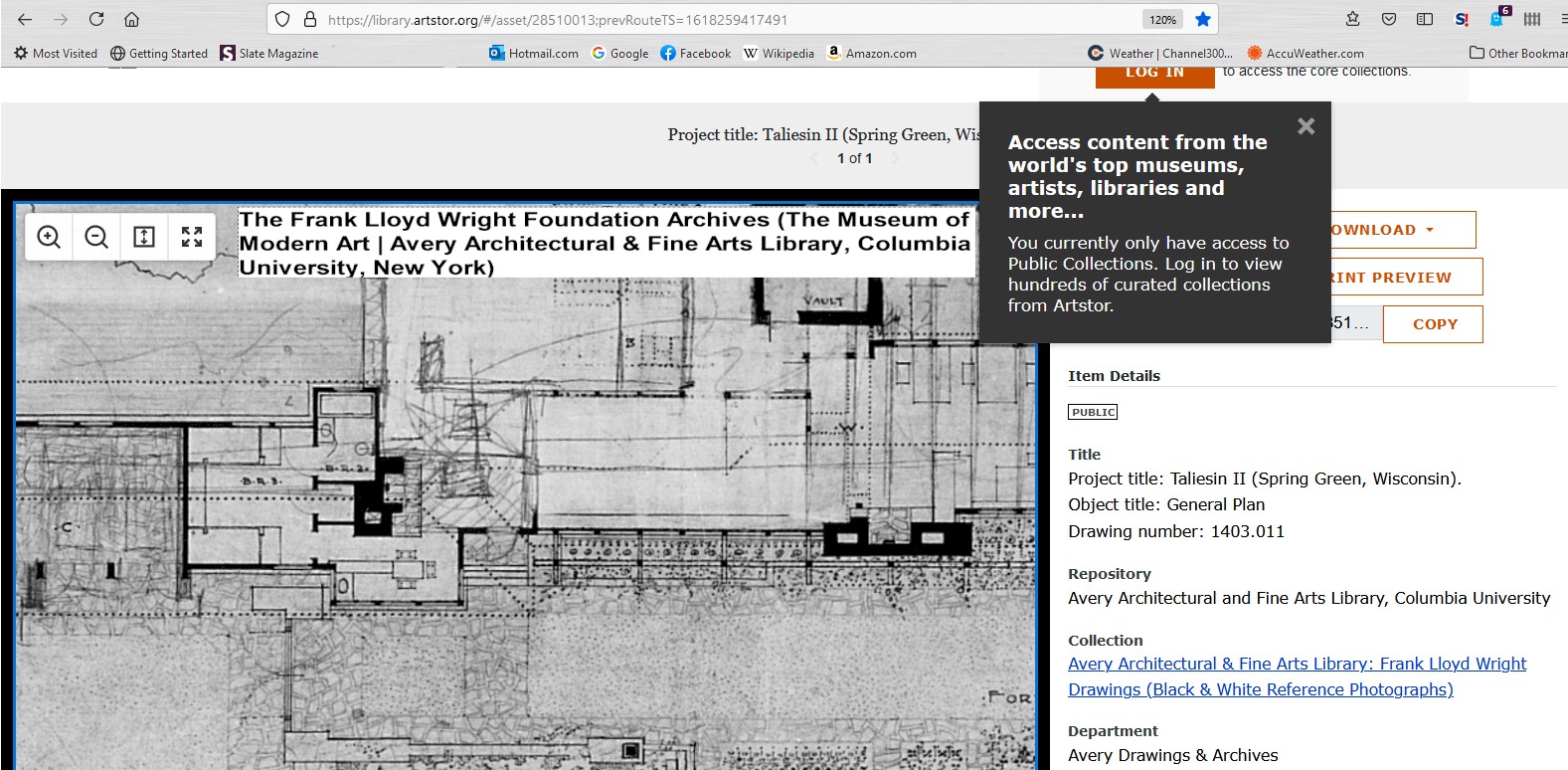

There are some drawings, like the one below I originally referred to as the “crazy-making drawing”:

That hell-spawn of a drawing you see is number 2501.003 at The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York). Click on the drawing to see a more humane version of it online.

However, I have never come across what appears to be 40 preparation drawings.

Still, I had to start and, fortunately, the office had black and white photographs of some of the drawings, too, which were easier on my eyes. And I could magnify them without the computer scan dissolving into only pixels.

Since my first room was where Frank Lloyd Wright’s Bedroom is today (what he used as of 1936)4 and looked at the entire space from 1911 onward (even before a room existed).

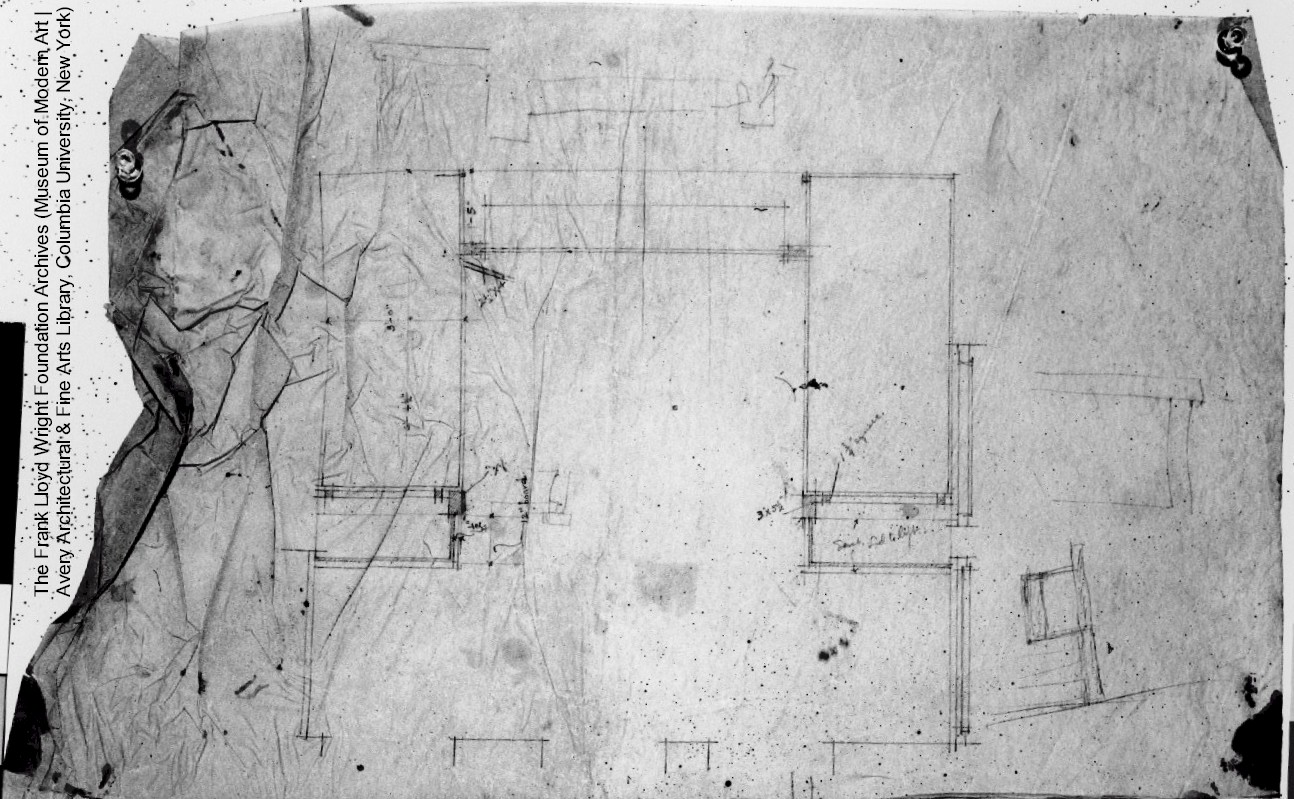

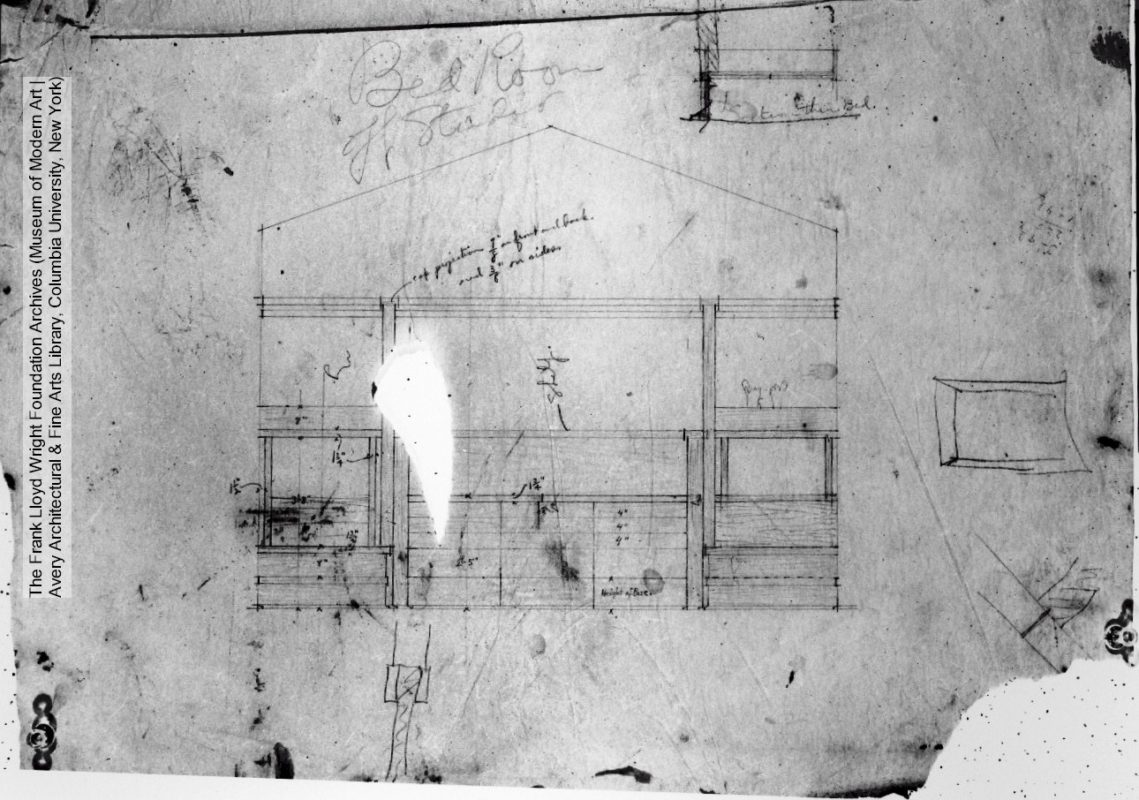

I’ll put an early drawing of Taliesin III below. First I’ll show the whole floor he drew in 1925, then a detail of his bedroom:

Main floor of Taliesin c. 1925. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives, number 2501.001.

A detail from drawing 2501.001, in color:

The room exists in the photo below under the shed roof beneath the arrow:

George Cronin took this photograph 1929-33 while on top of Taliesin’s Hill Crown. Looking (plan) northeast.

In 1935, he built a fireplace for this room

in this photo online.

Then he took over the space a year later, and added a terrace as he made this into his personal bedroom. The photo you see in this link from the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation has him sitting on the terrace with his daughters and members of the Taliesin Fellowship.

When Wright no longer lived in Wisconsin in the winter, he extended his bedroom onto the terrace in 1950, like you see below:

Photograph taken in 1957. William Blair Scott Jr Collection, OA+D Archives.

As a result of my work,

my “first go” at the detailed history of one room was over 100 pages long.

So you can see why I can walk through the rooms in my head in the past.

5 or 6 months later,

I was on the third room

(out of 10 rooms on that floor).

Then

the Executive Director5 came and asked me to complete the write up of the history of all of the rooms in this wing of the building

over the wing’s three floors, and totaling 20 rooms

in 10 weeks.

While listening to her, I was probably nodding. When she said I had to finish all of this in 10 weeks, I probably took on an expression of,

well,

“terror” might best explain it.

Truth is,

that led me to, an hour or two later, putting my forehead on the desk and crying.

10 WEEKS!…

I went home early.

So, that night,

I decided to throw out anything about the rest of the rooms that took place before c. 1950 and combine a few spaces.

And I did it!

In early April,

in other words, 10 weeks later,

I presented the Executive Director with 12 documents that had a total (as I recall) of 821 pages.

At least 821 is the number I remember putting in size 56+ font on my computer desktop for a couple of days after completing the work.

Then a month or two later Carol directed me to write Chronologies for the rest of Taliesin (over 100 rooms).

First published December 17, 2024.

The drawing at the top of this post, Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives Number 2501.048, is available here at JSTOR.

Notes:

1. wtf, Keiran: the estate is 800 acres. So much for this “Taliesin Historian” crap!

The NHL is for the 600 acres that Wright had and was owned by the Foundation when it received NHL status. In the 1990s, the Foundation bought the neighboring 200 acres, originally owned by Wright’s Uncle Thomas. This creates a land buffer.

2. In early 2020, the site owner, the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, completed what it had been doing for several years: moving all of its preservation and restoration staff from Taliesin Preservation back under its management. The two organizations still work together, but care of the NHL is again under the Foundation.

3. Note to those who are convinced that Frank Lloyd Wright didn’t refer to his home as Taliesin II or Taliesin III until Henry-Russell Hitchcock wrote In the Nature of Materials in 1942: Wright referred to his rebuilt home as Taliesin III in his autobiography first published in 1932. I know ‘coz that quote above is from my own paperback copy of it, published in 1933. Sorry – it’s just an ongoing argument in my head. Carry on.

4. Some people might think it’s weird that the Wrights eventually had two bedrooms, but I know people who also made that choice, because they sleep better.

5. I referred to Carol here when I wrote about “The Album”.