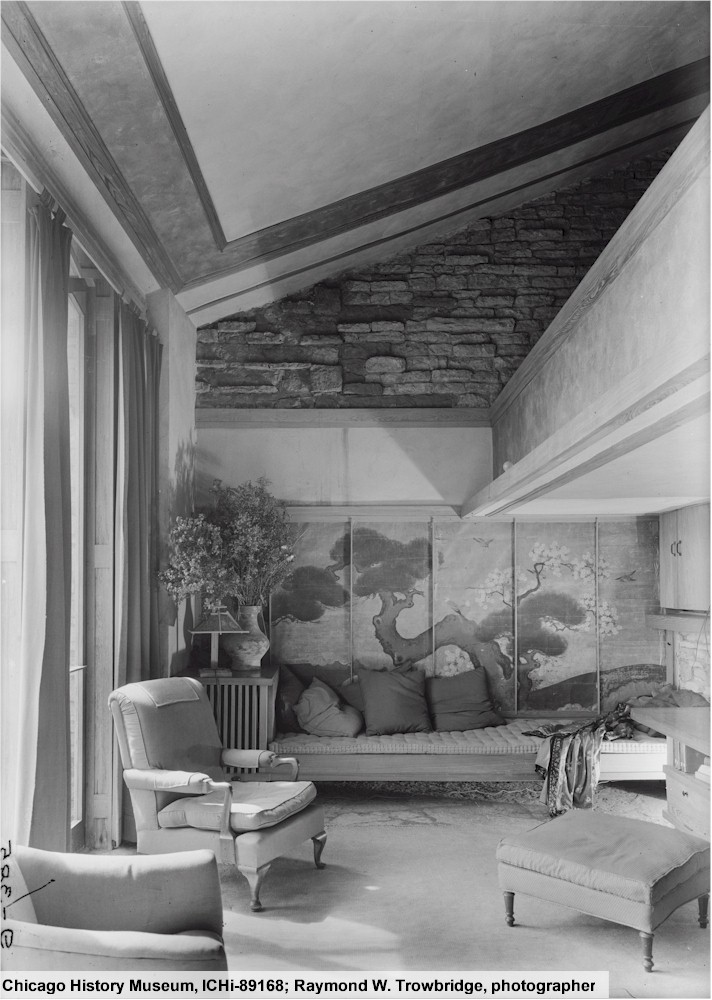

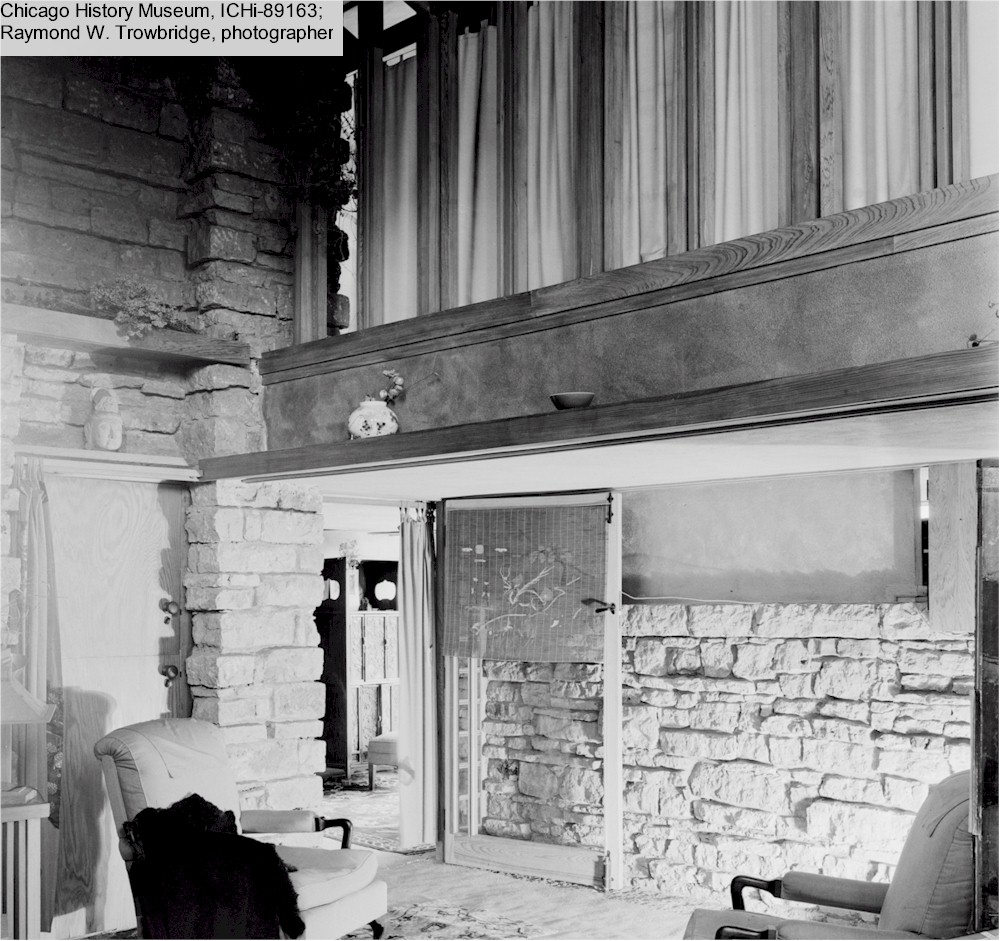

In my last post I wrote about a photograph of a wall that no longer exists at Taliesin. I wrote that the photo was taken by Raymond Trowbridge in 1930 and I’d explain it in my next post. That photograph showed the wall in the Loggia fireplace. The photograph above is by the same photographer and shows the other side of that wall. What you’re seeing is Taliesin’s Loggia. I’ll explain in this post how I (or Taliesin Preservation) got the photos and how I know they were taken in 1930.

First coming across the Trowbridge photographs:

In the winter of 1997-98 (3 years into my employment, then working seasonally at Taliesin Preservation), I had a part-time job in the preservation office working with photographs related specifically to Wright’s home (later his Taliesin estate, which includes the Hillside stucture, Romeo & Juliet windmill, Midway Barn, his sister’s home, Tan-y-deri, along with its landscape). Photographs are among the things used to help understand the history of the Taliesin estate and do restoration/preservation. The work was needed that winter because an Architectural Historian from Taliesin Preservation had apparently left his office in a bit of a mess.

So I got a job in the office (20 hours a week through the winter). I worked through the winter to bring order to the photocopies he’d left behind. As a result, I saw some amazing images for the first time.

Taliesin Preservation becoming aware of the photographs:

13 of them had been brought to our attention by Wright scholar, Kathryn Smith. She’d come across them while doing work in Chicago, photocopied them, and sent them to us, as part of what was described to me once as “preservation by distribution“. She’d sent the images maybe in the early 1990s. And she included all of the relevant information with the photocopies: collection ID-number, the photographer (Raymond Trowbridge), and who owns them (the Chicago Historical Society, now the Chicago History Museum).

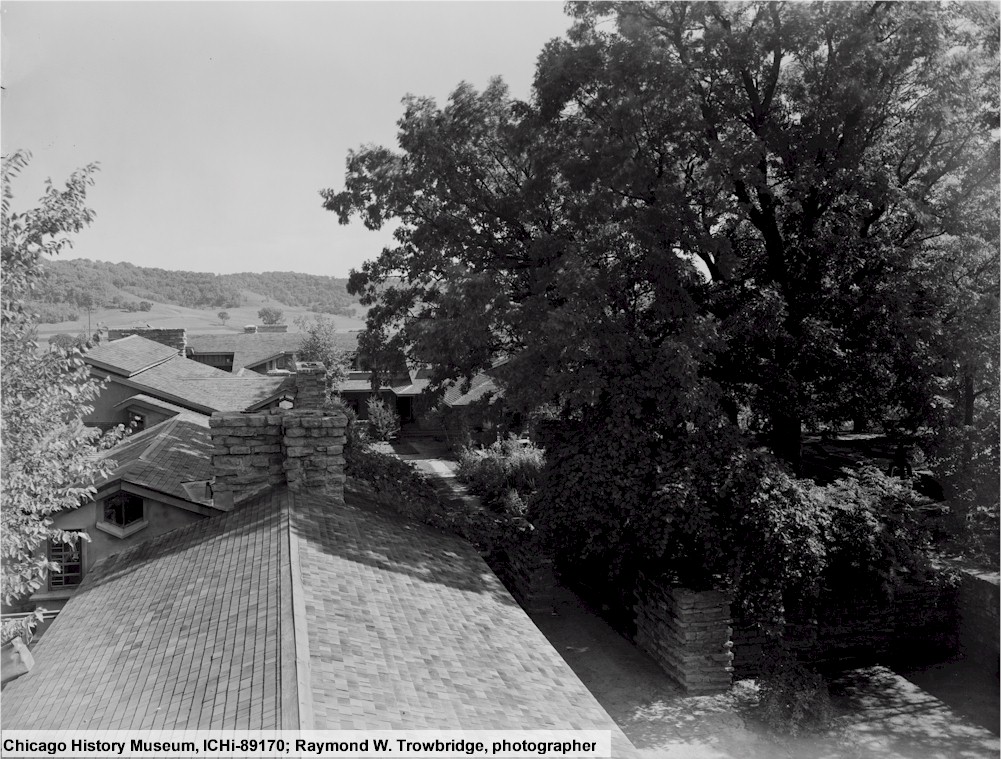

By their details, it looked like someone took them in early Taliesin III; so 1925-32. They looked like the photographer took the images before the Wrights founded the Taliesin Fellowship (in 1932). Trowbridge knew what he was doing with these images. They have wonderful composition and light balance, show the texture of Taliesin’s stucco walls, its wooden banding, and its flagstone.

In my work, I arranged these into the binders of photocopies we’d started to assemble. Then the winter ended, and I went back to my work giving tours.

My first trip to Frank Lloyd Wright’s Archives:

Almost a decade passed. I started working in historic research (along with tours), got a raise and made plans to travel before I found ways to spend it all. This took me on my first of several trips to Wright’s archives, which at that time were located in an archives building at Taliesin West, his winter home in Arizona. The archives included over 22,000 drawings, over 40,000 photographs, correspondence related to his life and his work (letters to and from family, friends, clients, and others), and many other things I’m sure I never saw. While there, I went to the archives every workday. Monday to Friday, I showed up at 8:15 a.m., took an hour for lunch, and stayed until they ended their work every night (usually a little after 6 p.m.). And, bonus, I often got to do this in winter.

Here’s a note for you:

The second time I went to the archives, I thought I would save money by going in the summer. I don’t know how hot all of Arizona gets that time of year, but going voluntarily to Scottsdale in July is not worth any money that you save. That caution on Arizona’s hot temperatures might also apply in May and definitely June, August and early September.

The first find by coincidence:

On one of my trips, I hit my research goals early in the afternoon on Friday. I remembered the name Raymond Trowbridge and went looking for correspondence with him.

The archives has nine letters between Wright and Trowbridge from 1930 to 1933. In the first letter, ID #T001E02 (written September 20, 1930), Trowbridge answered a question that Wright had written to him (that letter’s not extant). Wright had apparently asked what type of photography equipment Trowbridge had “with me at Taliesin.”

Looking at Trowbridge’s photos, I concluded that he was probably talking about the photographic session he’d just had, in which he took the 13 images. Because the images they were definitely taken during the summer (like the one below). So that made these photos from maybe August or early September of 1930. Cool.

I tucked that info away in my brain. When I returned to Wisconsin, I looked at the Trowbridge photographs, and changed their dates to 1930-33.

A while later I found out more about Trowbridge:

A few years later, when I had some time in the middle of the week, I sent a comment via email “To Whom It May Concern” at the Chicago History Museum. I explained who I was and that they needed to change Trowbridge’s dates on his photos at Taliesin. They’d written that all of his photos in their collection were 1923-36,1 but those dates were wrong. I told them the dates for his images Taliesin should be 1930-33.

The next Monday, I got an email from someone in the Rights and Reproductions Department telling me that Trowbridge didn’t take photos of Taliesin.

I replied that, well actually he did. Then I explained Kathryn Smith, the collection she’d sent, and I emailed a scan of one with its ID number (this scan, seen in my blog post, “Taliesin as a Structural Experiment”, was published in the booklet “Two Lectures on Architecture” in 1931).

Good news from the Chicago History Museum:

I heard back from this person several hours later. She wrote that, oh my god, yeah! They did have these images—as glass negatives. Someone had misfiled them and my email helped them locate them properly. And she told me they’d get high resolution scans & contact me after they put them onto an online photo sharing and storage service. A day or two later I accessed and downloaded these beautiful scans.

The last stroke of luck:

Then in 2018, while putting together a presentation for the annual Frank Lloyd Building Conservancy conference, I wrote again to the Rights and Reproductions Department at the Chicago History Museum. I asked how I could get permission to use one of the images, and how much Taliesin Preservation had to pay.

Even though I wasn’t paid to speak at the conference, I’d have to work out image permissions; I hoped I didn’t have to pay, but you never know.

The told me I didn’t have to pay for or sign anything. The photographer had died 83 years before, making all of his images in the public domain. I only have to give the information you see on the images: who owns it, its archival number, and the name of the photographer. And I wrote this in the manner that they asked for (which is why the photographs give Raymond Trowbridge’s middle initial).

All of these things:

- Kathryn Smith sending us the images (and the former staff member leaving the office in a mess);

- finding the correspondence related to them because I had a couple of hours at Wright’s archives;

- getting high res scans because I had some time in the winter to write to the image owner, and

- finding out while I was setting up a lecture that they’re in the public domain

remain some of my best career-related serendipitous experiences as an adult.

First published, 1/28/2021.

Raymond C. Trowbridge took the photograph at the top of this post. It is Chicago History Museum, ICHi-89168, and is in the public domain. This is the larger version of the image on the Keiranmurphy.com website.

1. They gave the dates 1923-36 because Trowbridge became a photographer in 1923 and died in 1936 (actually, they first said 1935, but that must have been a typo, because the site now says he died in 1936).

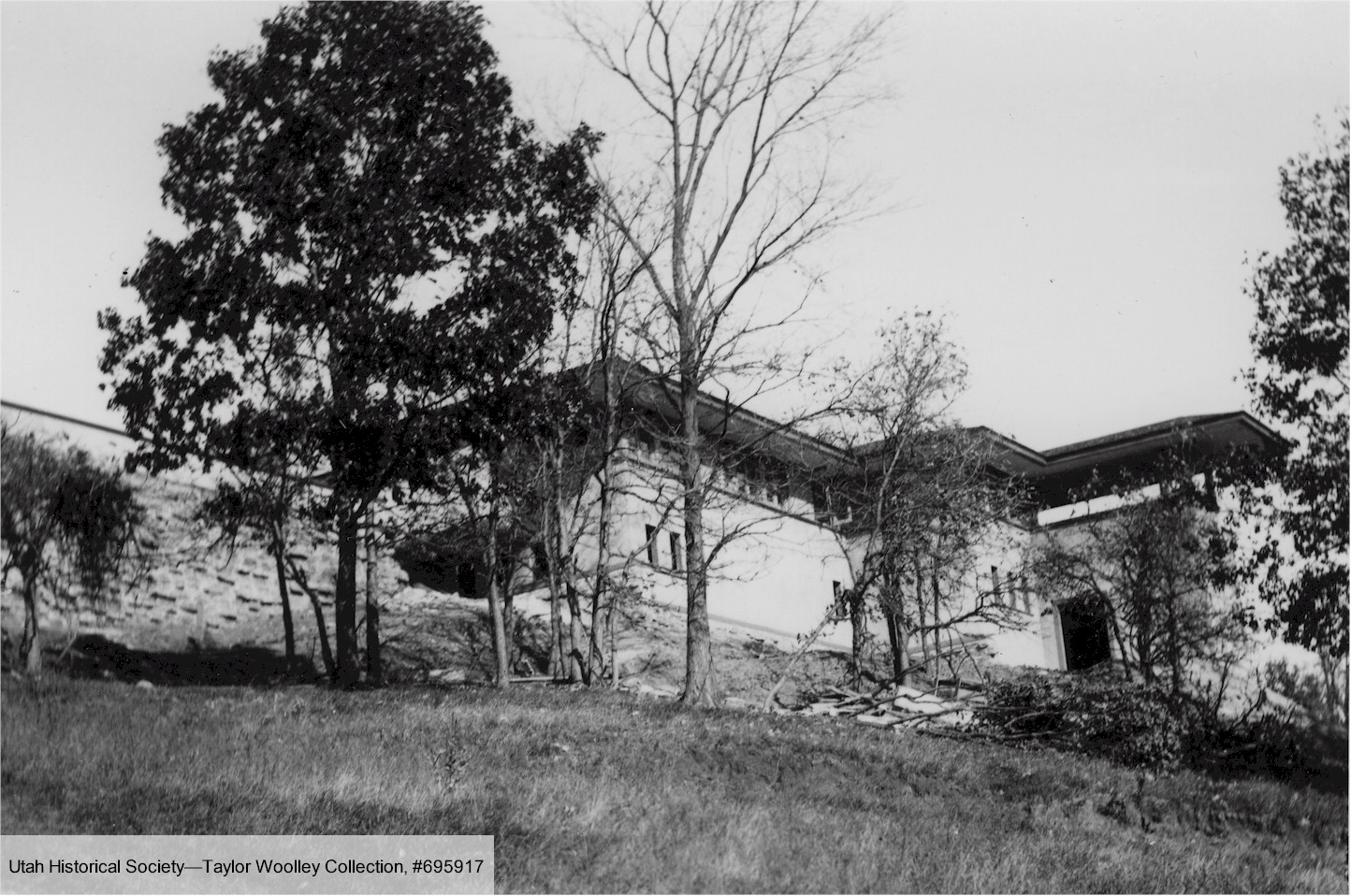

You walk up the steps at Taliesin to Wright’s studio at Taliesin (the north wall of the studio is to the right). The parapet from the Taliesin I photo ended at the stone that is to the left of the tree trunk (the tree trunk is to the left of the window that’s on the extreme right in the photograph) .

You walk up the steps at Taliesin to Wright’s studio at Taliesin (the north wall of the studio is to the right). The parapet from the Taliesin I photo ended at the stone that is to the left of the tree trunk (the tree trunk is to the left of the window that’s on the extreme right in the photograph) .