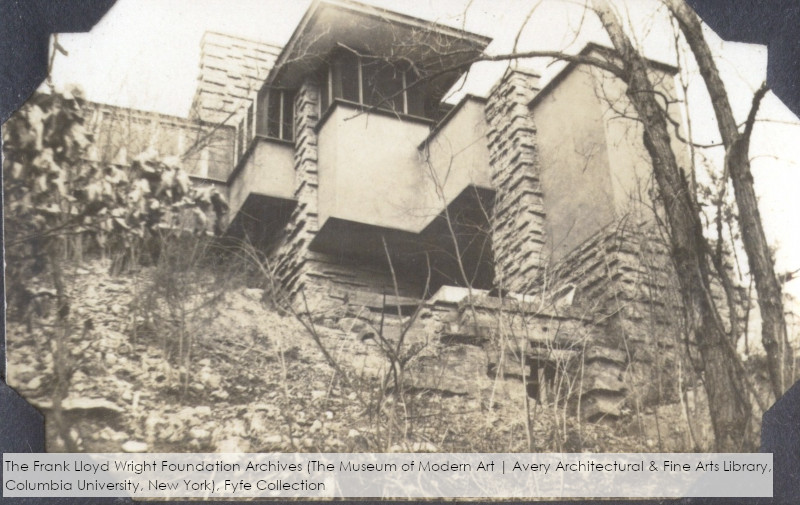

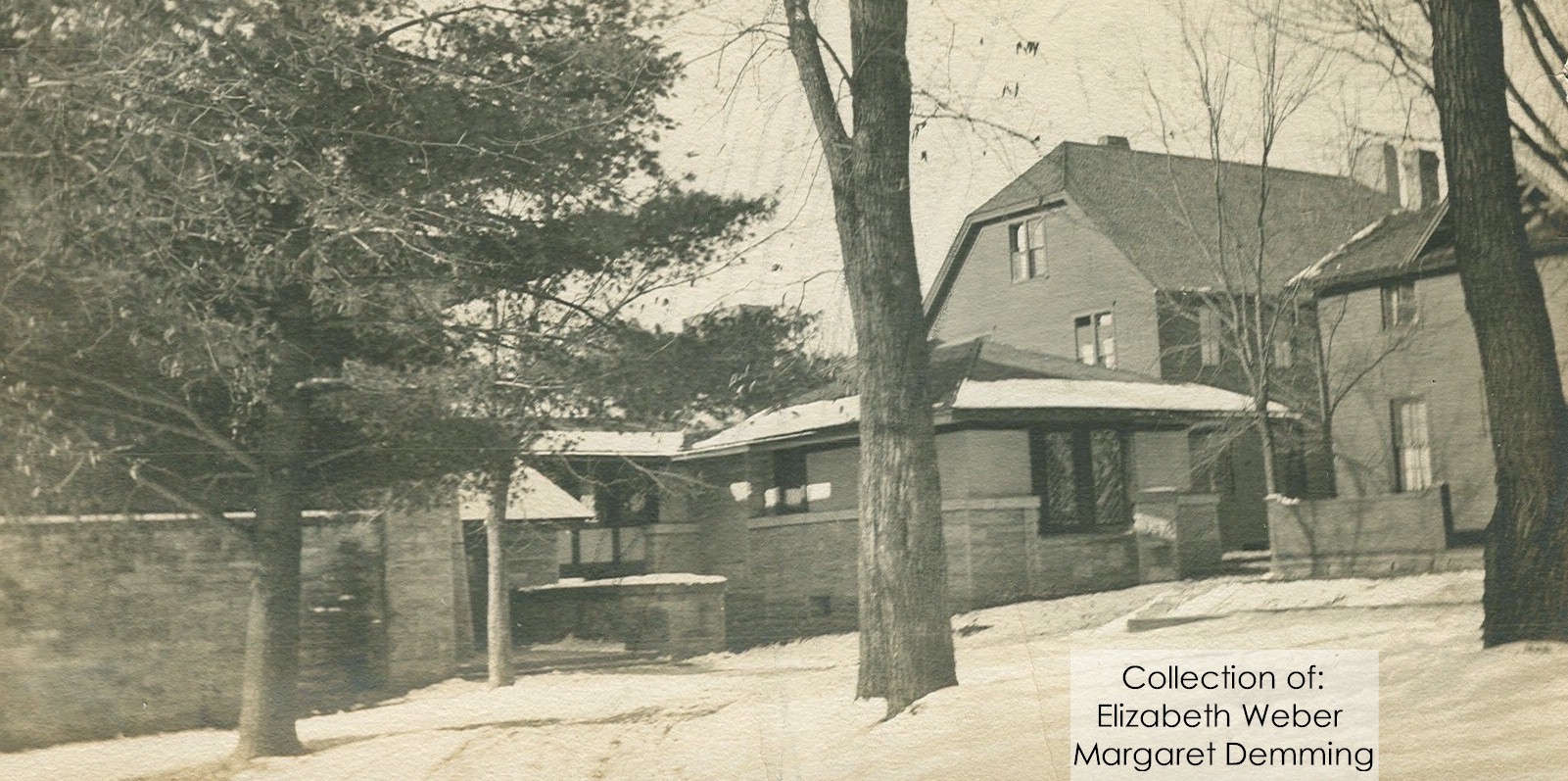

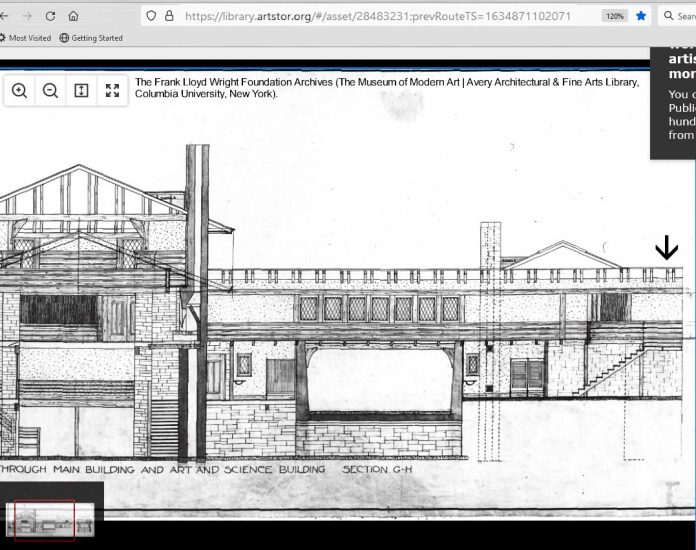

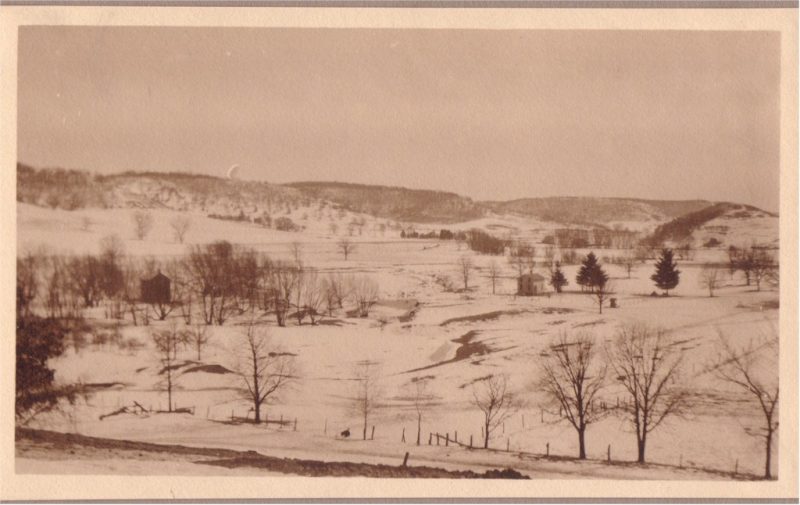

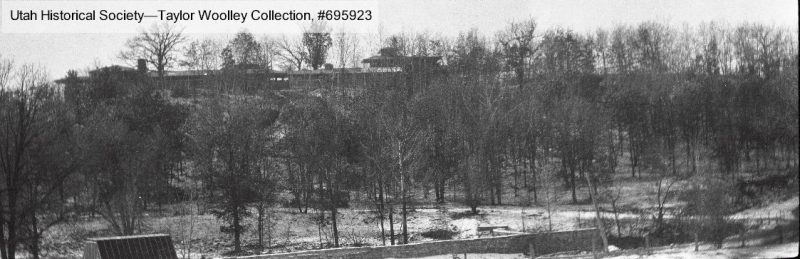

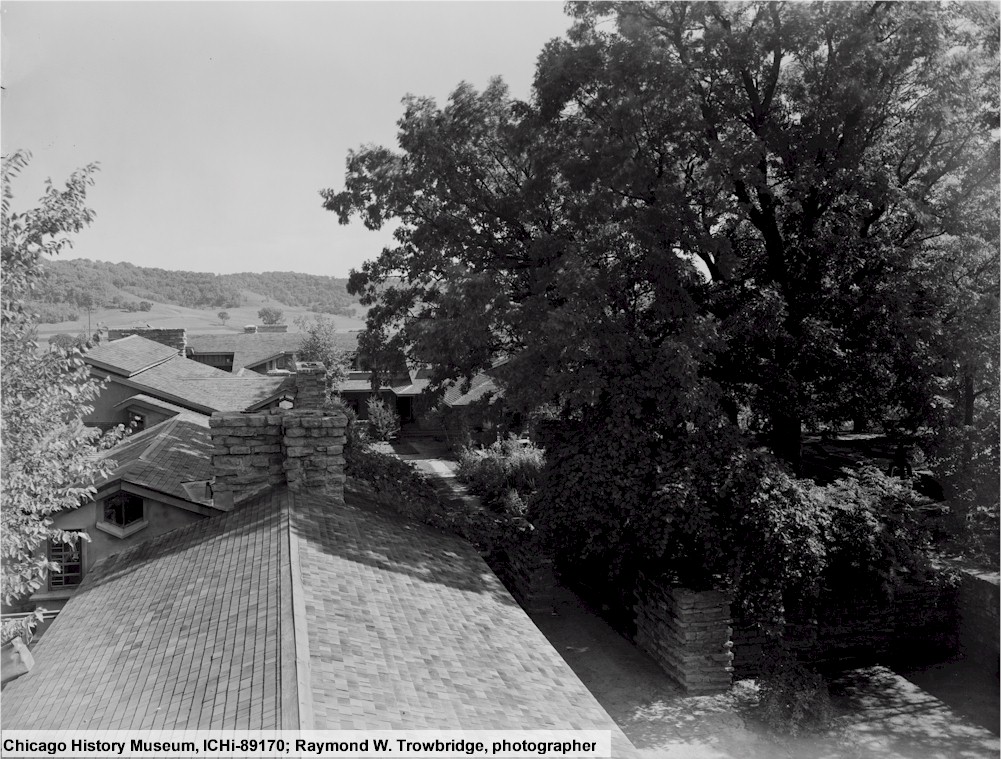

Beye Fyfe took this photo while looking up at Taliesin, either in the late fall or early spring. It’s a close-up of that balcony I talked about in my last post.

That is: what is carbide gas?

I discovered this while researching the history of Taliesin’s lighting and electricity and will write about it in this post.

Plus, this gave me a chance to remember what a “mole” is from Chemistry class.

Taliesin’s lighting:

In Taliesin’s earliest years, Wright got light for his house by making his own Acetylene gas and piping it into gas light fixtures in his home.

I’ll write below what this has to do with the photograph at the top of this post.

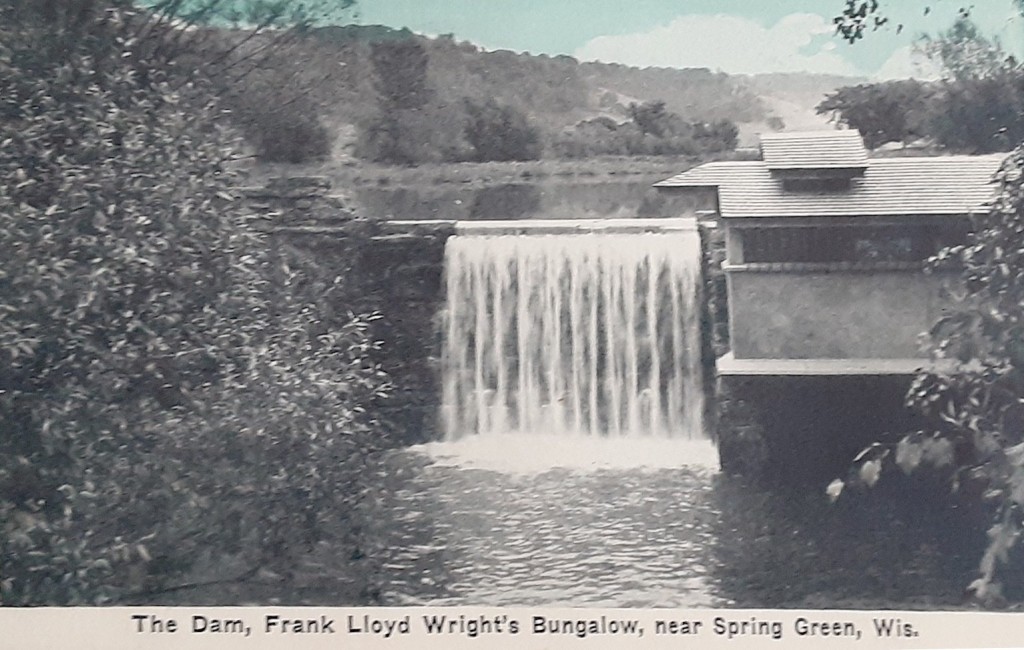

I probably read about Taliesin’s old light system while researching the dam at Taliesin.

So,

I gathered information by reading oral histories from members of the Taliesin Fellowship. That gave me a clue of what was going on at the dam.

Some of these oral histories were done by Indira Berndtson, the (now retired) Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Administrator of Historic Studies. This was great, because she interviewed former Wright-apprentice, Wes Peters, who died in 1991.

While “Wes” had never seen the system, he told Indira (in his July 26, 1990 interview) that Wright created his own acetylene gas for Taliesin, starting after about 1913.

But Wes didn’t call it Acetylene. He called it Carbide gas.

Because:

you got Acetylene gas by dropping water on calcium carbide.

And I think Wes was right about the year 1913.

How do I know?

The first page of the June 19, 1913 edition of Spring Green’s newspaper, The Weekly Home News had this:

Work has started at Frank Lloyd Wright’s summer home. B.F. Davies has a crew of men laying water mains, which will supply all the buildings with water and also irrigate the gardens, vineyards and flower beds.

I thought he had the hydraulic ram at his dam earlier than that, but getting the water supply could have done more than just water the garden.

I don’t know how Wright came up with this idea, but he had to get something for his home he was building in the country, away from any settled area.

And he could have gotten local help.

After all,

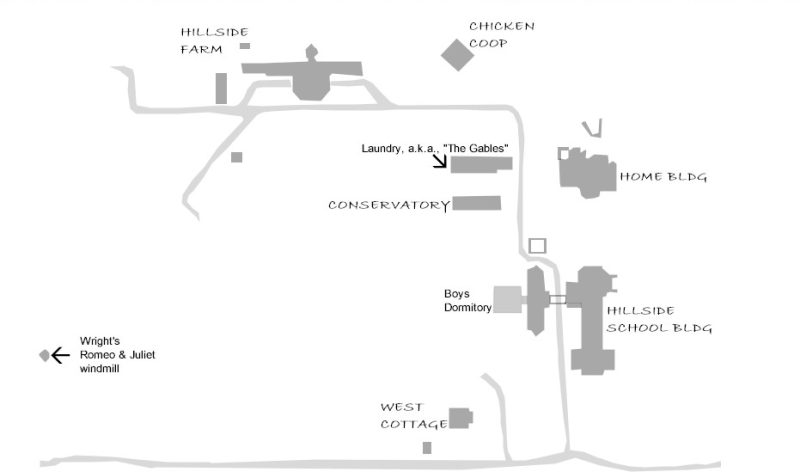

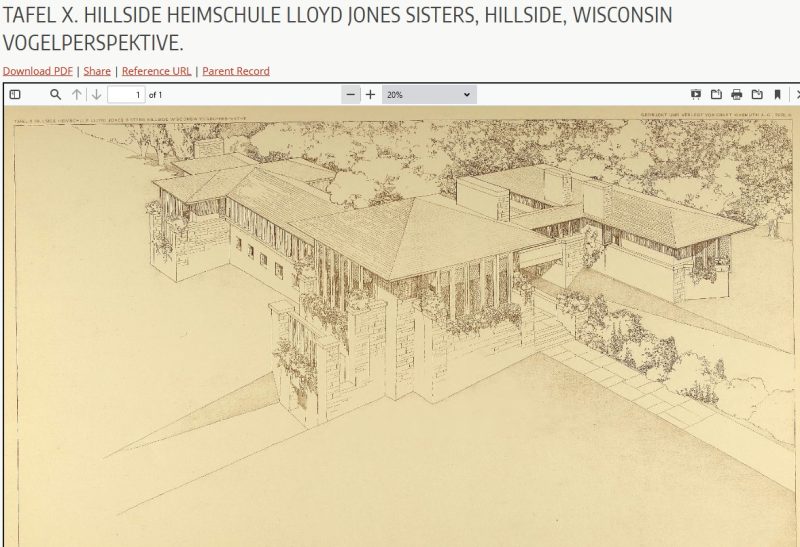

about a mile away, his aunts had their Hillside Home School. They started it in 1887 and it had gas light, too.

It says so in their school prospectus:

The school building is a fine stone structure, with a well-equipped gymnasium, shop, home-science kitchen, and music-rooms. The Lawrence Art and Science rooms are equipped with the most approved appliances, and so thoroughly equipped that they meet every need of the work. The entire plant is heated by steam, lighted by gas, furnished with numerous bath-rooms, and supplied with waterworks.

Hillside Home School prospectus for 1913-14 school year, 6.

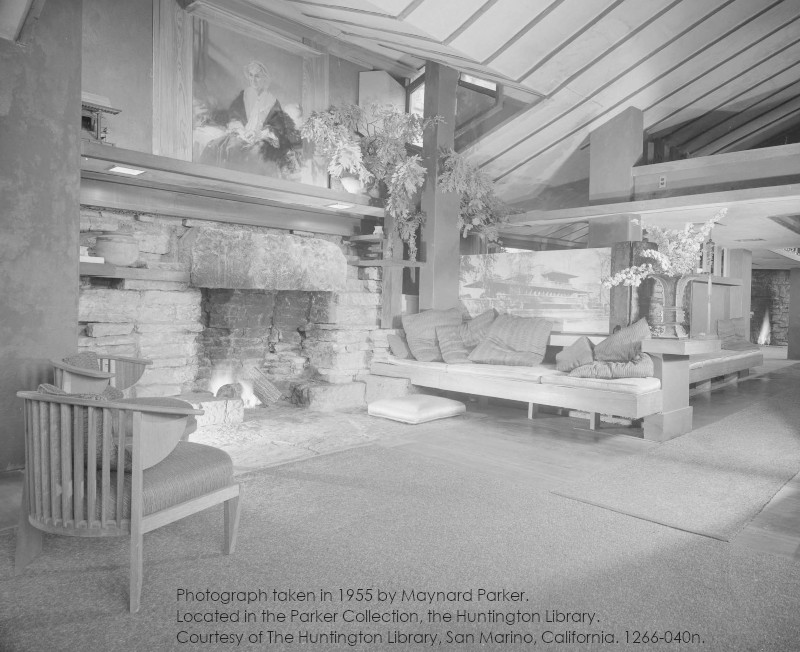

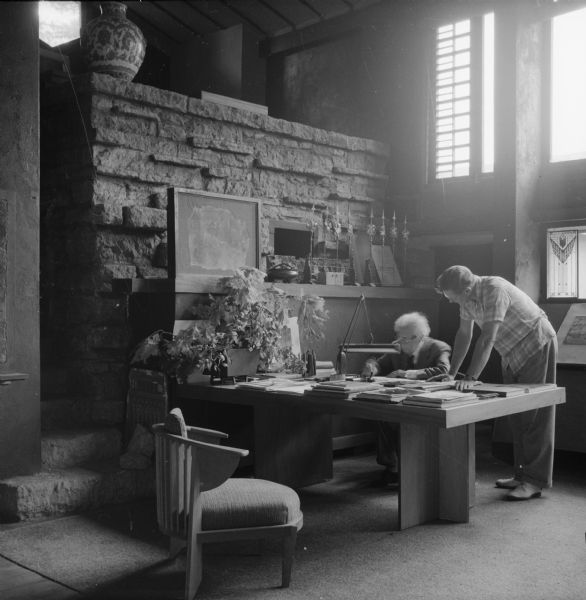

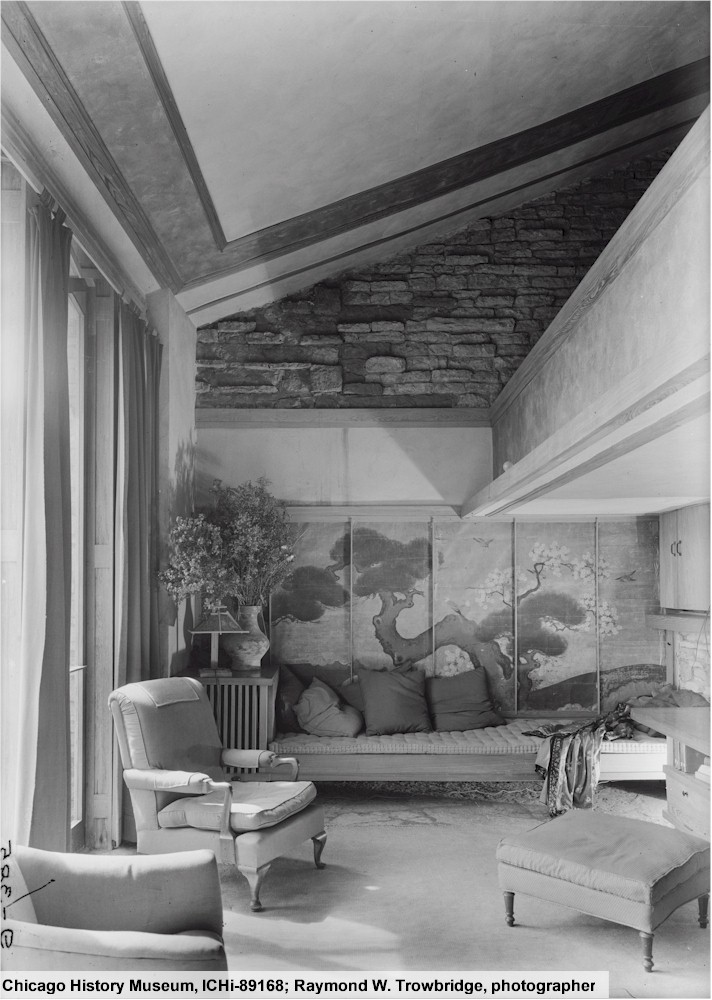

You can see some gas light fixtures in this an old interior Hillside photo:

Looking west in the Assembly Hall at the Hillside Home School, 1903-1908. If you took a Highlights or Estate tour at Taliesin today, you would see the balcony and the stone piers, but everything else in the background is different, because of the 1952 Hillside fire. You can see a current photo looking in the same direction in my post, “Charred Beams at Taliesin“. It’s the eighth photo down.

Returning to what Peters said:

He said that when he first became an apprentice under Wright in 1932, Taliesin had electrical light.

Wright expert Kathryn Smith and I realized the hydroelectric generator was constructed in 1926.

But the tank where they used to put the calcium carbide was still there.

I think the entrance to the tank is in the photo at the top of the post. You see the black rectangle in the stone at the bottom of the photograph.

Like I said:

This is another thing learned at Taliesin: carbide gas.

When you look for that in Wikipedia, it directs you to the page for Acetylene.

… shoot, I don’t think anybody even covered Carbide or Acetylene in Chemistry class in high school.

I just remember learning what a mole is, which I still think is totally cool.

I mean: you could figure out how many atoms there were in a gram of any element. The certainty of this was intellectually satisfying.

While I was reading up for this post, I found this page from “Old House Web” on people generating their own gas for their homes outside of the city.

Lastly:

in regards to the interview with Wes Peters.

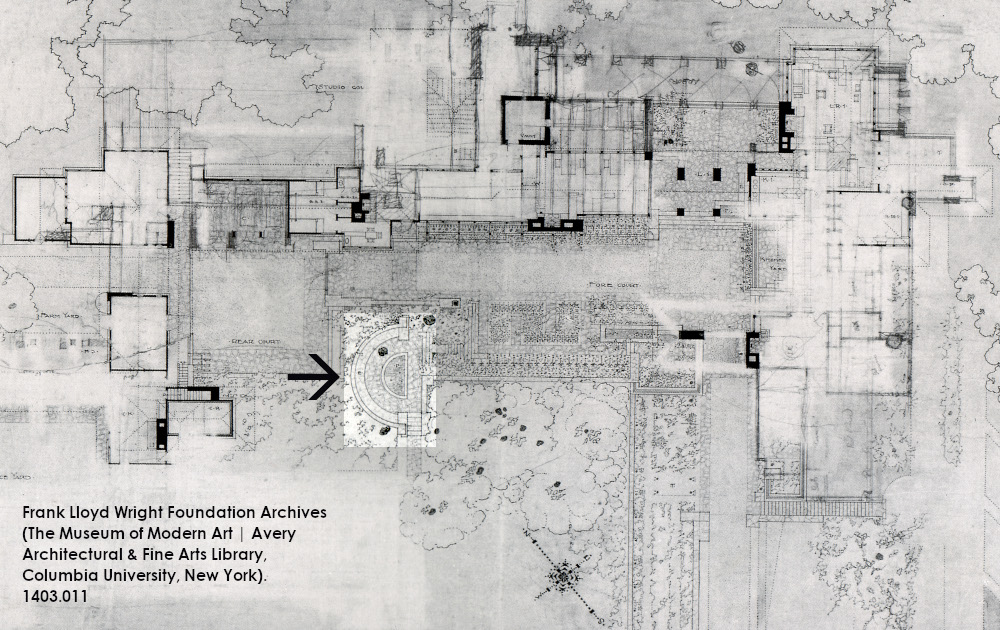

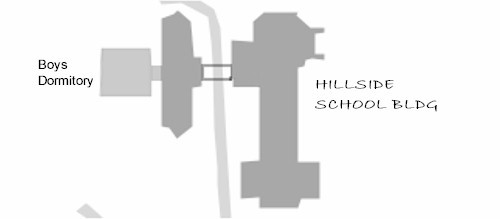

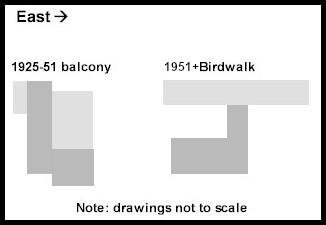

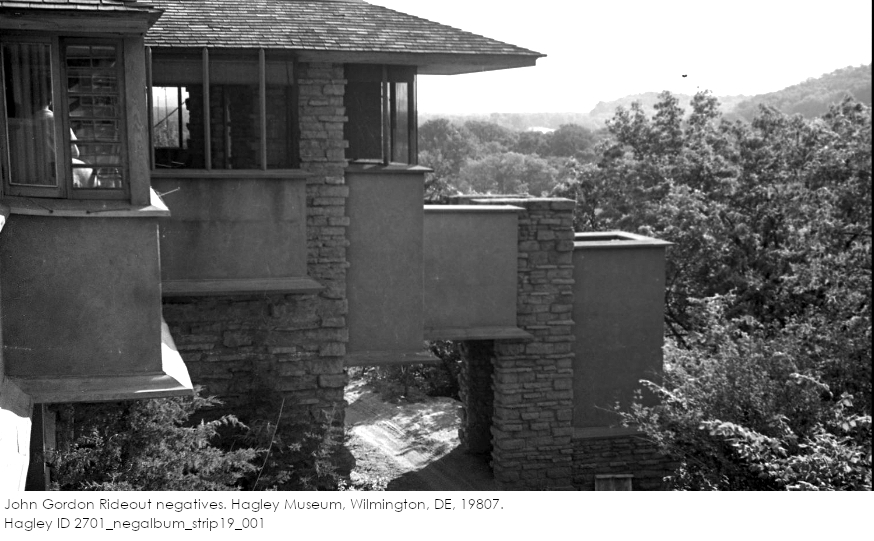

During the interview, he said that he thought the tank for the calcium carbide was under the pier where the Birdwalk is today.

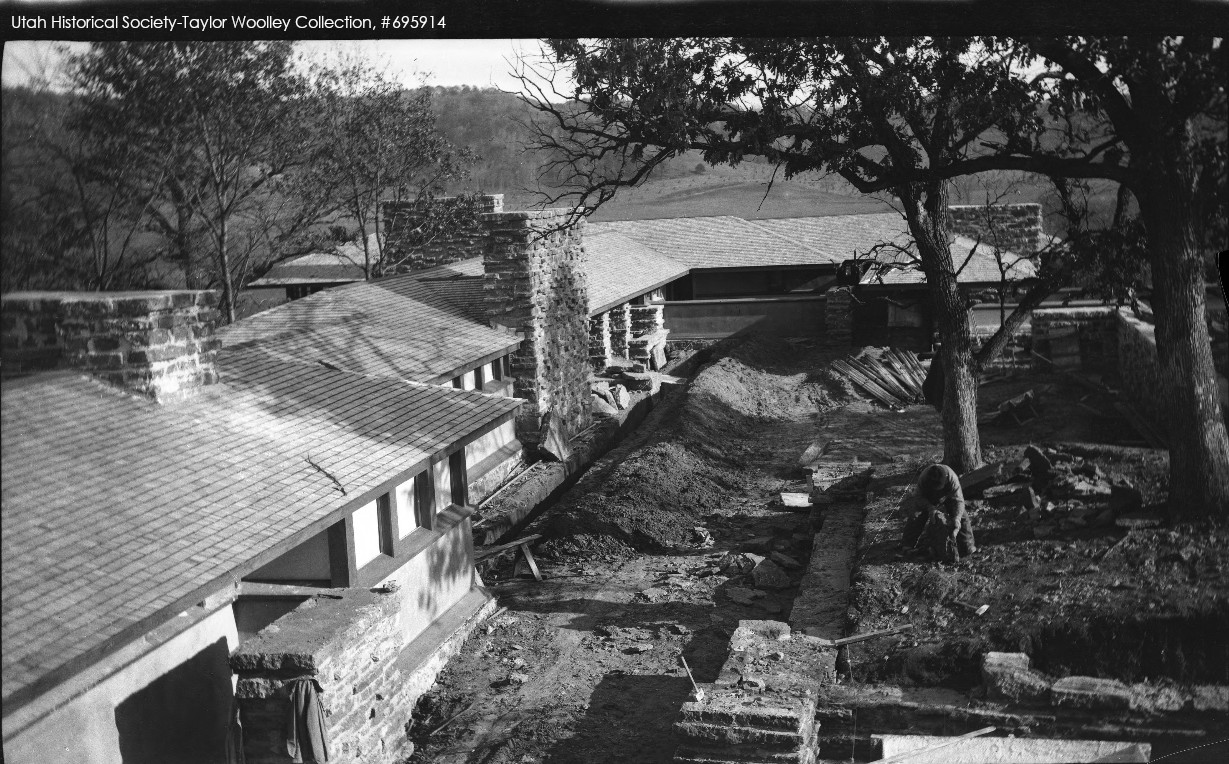

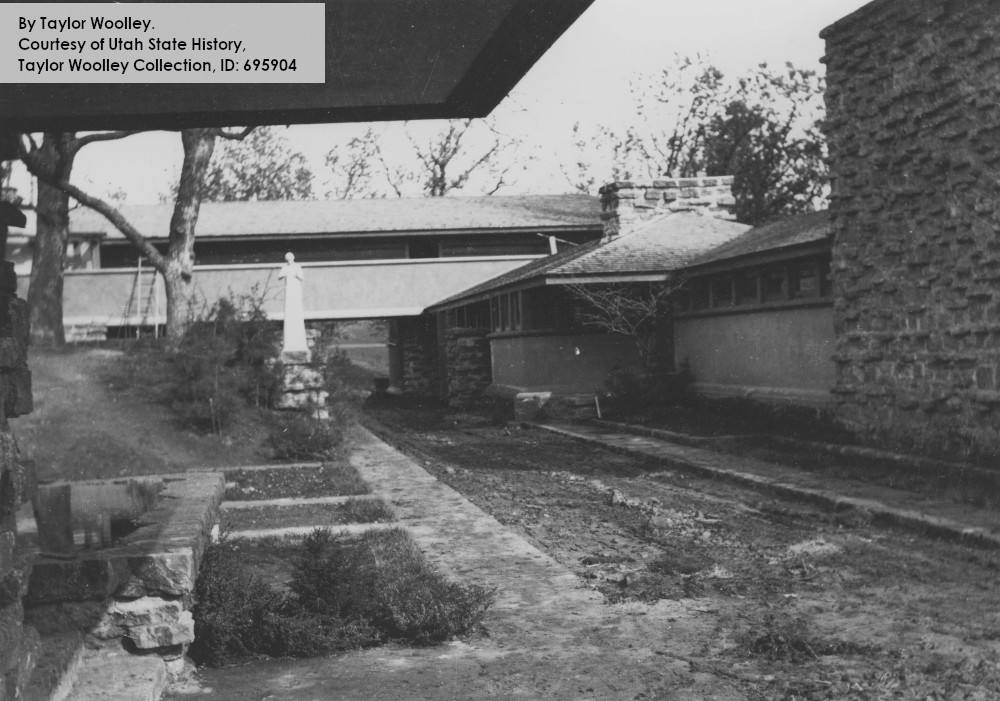

While I researched the Birdwalk, I realized the stone pier under the balcony was not in exactly the same place as the stone pier that holds up the Birdwalk. It doesn’t match up with old photographs, and I can’t figure out if the stone matches up.

So,

since I didn’t have exact measurements of where all of these things are, and were, I put two photographs together on a page on my computer, then drew a rectangle and moved it pixel by pixel to approximate the positions I could see in photographs.

This resulted in the drawing below. In my picture, the stone is dark gray and the plaster is light gray:

It’s not perfect, but it gives you a sense of how the Birdwalk and the balcony stood in relation to each other.

You can compare the photos from my last post, or below:

The photograph at the top of this post was taken 1933-34 by William “Beye” Fyfe (1910-2001 at age 90) while he was an apprentice at Taliesin. His photograph helped me to date a change made at Taliesin’s Guest Bedroom.

Posted March 24, 2024

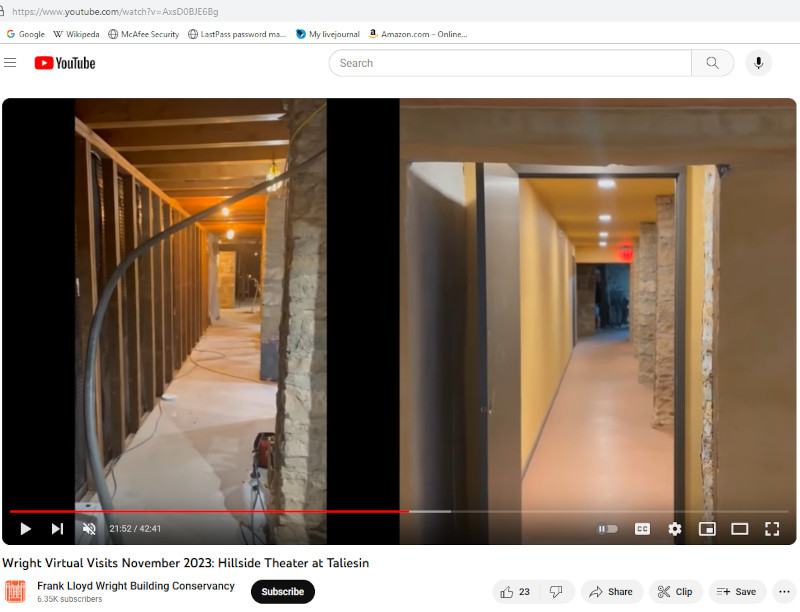

Oh, and if you want to go further down the hole, you can watch this for information about Acetylene gas. I found this on YouTube from “Tractorman44”. He explains how acetylene gas is made from carbide with water:

And then you can read about carbide lamps in miner’s helmets.