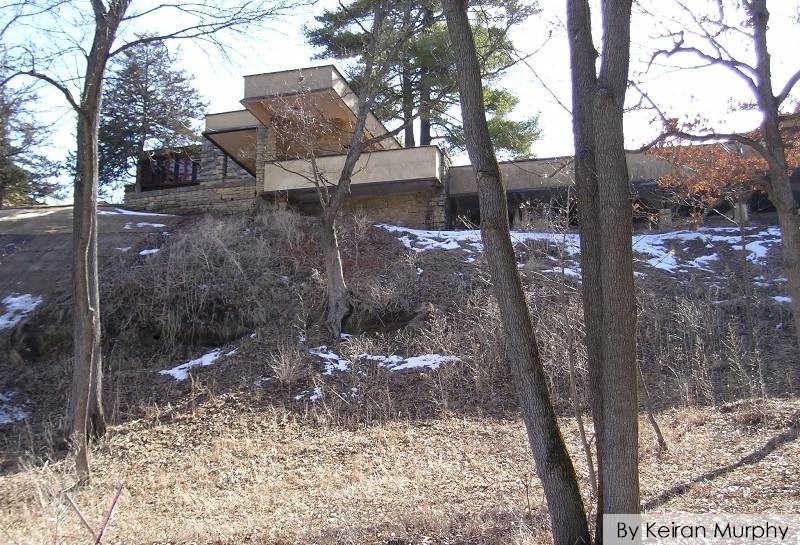

Looking west at the Hex Room in the Frank Lloyd Wright Visitor Center. I took this photo in February of 2005. You can see through the Hex Room, which is the room with the red roof and spire straight ahead of you. The clear view through the room is two vertical rectangles. If I had been in the room you’d see me sitting at my desk at the bottom of them.

While I studied Art History in Graduate School, being the Taliesin historian was a career I “fell” into. And that’s what I’m going to concentrate on in this post.

As I’ve written a couple of times, I started at Taliesin in 1994 as a tour guide during the summer. Guiding was all I wanted at that time, since I was in school and hoped to get a Ph.D. eventually. I wanted to teach Art History to other people.

However, I had no teaching experience.

I thought doing tours would help me figure out if I could even speak in front of people. Let alone if I could talk to, eek, strangers.

It turns out

The skills I’d learned in Graduate School were suited to the tapestry of information laid out everywhere at Taliesin. I swallowed it all in huge gulps.

Working exposed me to info on:

- All of the buildings of Wright’s career (here’s a list at Wikipedia)

- His family

- Both the family he was the head of, and his Lloyd Jones family in “The Valley” where he was impacted by the local nature.

- The history of Unitarian Universalism

- The history of the kindergarten (I wrote on that on my first post about the Hillside building)

- Like, the first kindergarten in the U.S. was in Wisconsin

- The Wisconsin Idea

- Lots of things about Historic Preservation

And other things I don’t want to bore you with.

Then

There was that winter of 1997-98 that I worked in the Preservation Office on the photographs (I wrote about it in “Raymond Trowbridge Photographs“).

At that time,

the Preservation Office stood in an old horse stable at Taliesin. Apprentice Lois Davidson Gottlieb took a photograph of it in 1948:

A link to her book is in my post, “Books by Apprentices“.

The office changed when, in June 1998, a tree hit Taliesin during a storm (photos on Taliesin Preservation‘s facebook page, here). So the Preservation Office moved out and the staff of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation (which owns Taliesin and the estate) moved in. This way they had an office in Wisconsin.

Eventually, the Preservation Office transferred everything to a room on the third floor of the Frank Lloyd Wright Visitor Center. That room was/is known as the “Hex Room” (because it’s literally a hexagonal). A photo showing the Hex Room underneath the spire is at the top of this page.

That office got me closer to being the historian:

When the Preservation Office moved in, they brought all of the historic photographs and other historic information. Yet, they realized that they’d lost the staff person who looked after it, and they needed someone who could sort through it. And, since I had worked with the information before, they brought me in to organize it.

Actually,

they didn’t “bring” me “in”. I was already there. I worked a floor or two below them, in the Taliesin tour program.

So, I spent 2001-02 re-organizing the files, adding more historic photographs, and began writing historic information.

Followed in 2002 by Tours

In that year, people in the Taliesin tour program “tapped” my brain to answer weekly questions from tour guides and staff during the season. My answers were on one page that was included with the weekly schedule. They named this feature “Hey Keiran!”.

This gave me a different cache of historic knowledge.

Like, why I explored whether or not Wright designed outhouses at Taliesin.

Et al.

Then, in 2002-03

They were planning the Save America’s Treasures‘s project at Taliesin.

I wrote about a window found during the SAT’s project in this post.

One day, while all of the infrastructure was being put together for the upcoming project, I was in the Hex Room. The Executive Director and Taliesin Estate Manager1 were talking on things involving the history of Taliesin. One part of the building was going to touch on the area the project.

The history of Taliesin’s Porte-Cochere came up. The Porte-Cochere became the “Garden Room”, which is in this photo. While we all talked, I told them them information about the space that I knew from books that I had read.

(like Curtis Besinger’s Working With Mr. Wright, which is in my “Books By Apprentices” post).

They realized

it was smart to have someone who knew that much sitting there in the office. They asked me to write chronologies on a few rooms at Taliesin that were going to be impacted by the upcoming project.

Eventually

that Executive Director asked me to write histories of every room at Taliesin from c. 1950-2005. Architectural historians told me my work was fantastic, so I kept going. That gave me the freedom to pursue things when I saw something, or came across something, that made me think,

“Huh. I wonder what’s going on there?”

It’s why I figured out that room was in that photograph that “one time before Christmas“.

I mean, Frank Lloyd Wright’s way of teaching his architectural apprentices was to have them “learn by doing”. And I learned the history by studying the spaces. The questions I asked were “what happened there”, and “when”. I often found the answers to the questions in the buildings themselves. This full-sensory experience of learning the history inserted information into my mind.

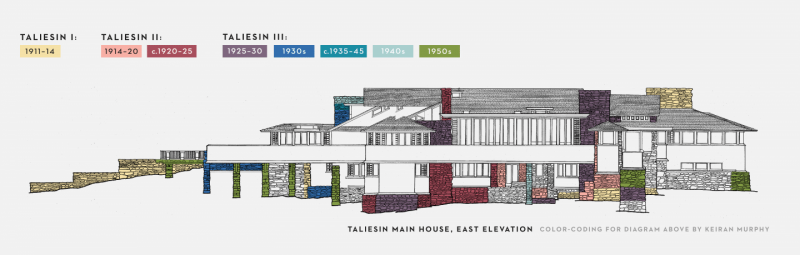

Around that time, I worked on color-coding the stone in drawings of Taliesin to figure out when he was laying out certain stone sections. I guiltily made changes to the drawing, but after awhile, it looked pretty cool. The drawing was included in the article I wrote for the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly, “An Autobiography in Wood and Stone“. You can see that illustration on that page, but I also placed it below:

I still don’t believe that I

“know more about Frank Lloyd Wright than anyone.”

as told to me by my oldest sister. She never believed me when I said that’s not true.

I mean,

there are “Frankophiles” out there who know every window that Wright ever designed.

They know the layout of every commission he did and his relationship with the clients.

They know all about the furniture designers he worked with (here’s one I know, anyway).

And more things I can’t begin to wonder about.

But the history of Taliesin? Yes: I think I know that very well.

First published April 28, 2022.

1. I mentioned in Jim in the post, “A Slice of Taliesin“. I wrote about Carol (the ED) in my post about “The Album“.