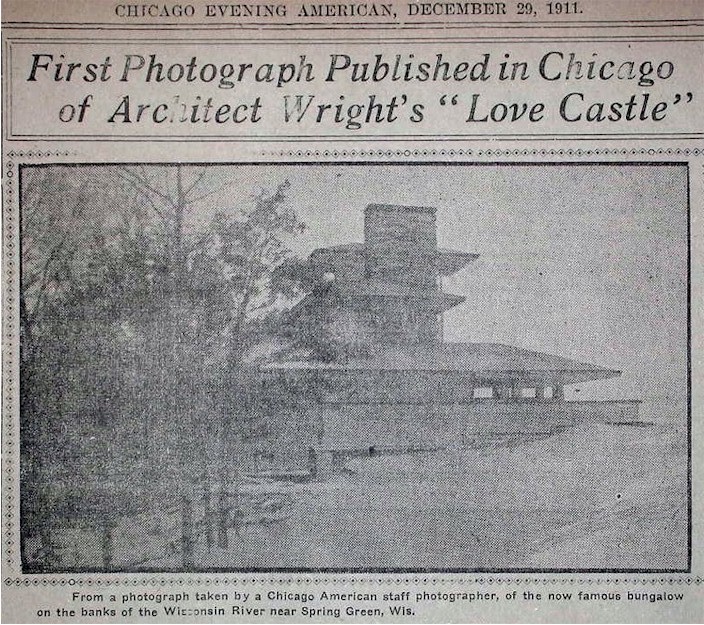

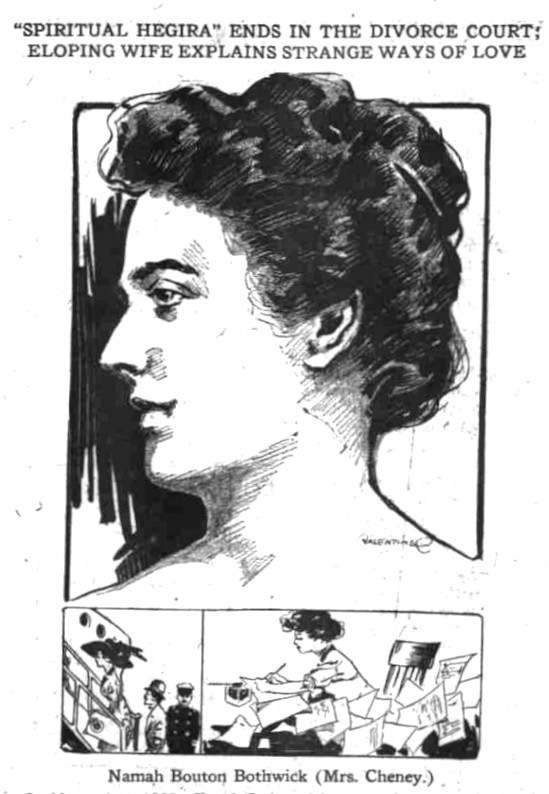

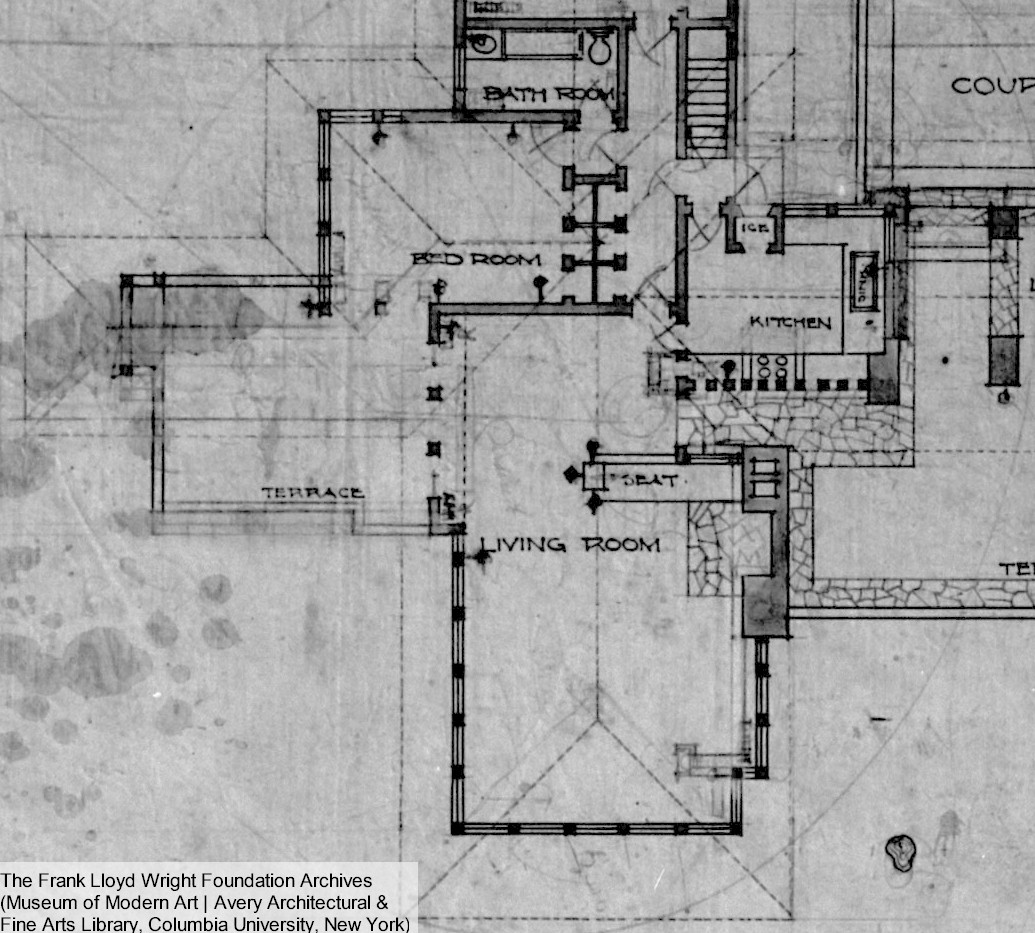

Drawing of Mamah Borthwick.

People have asked me this question about Mamah

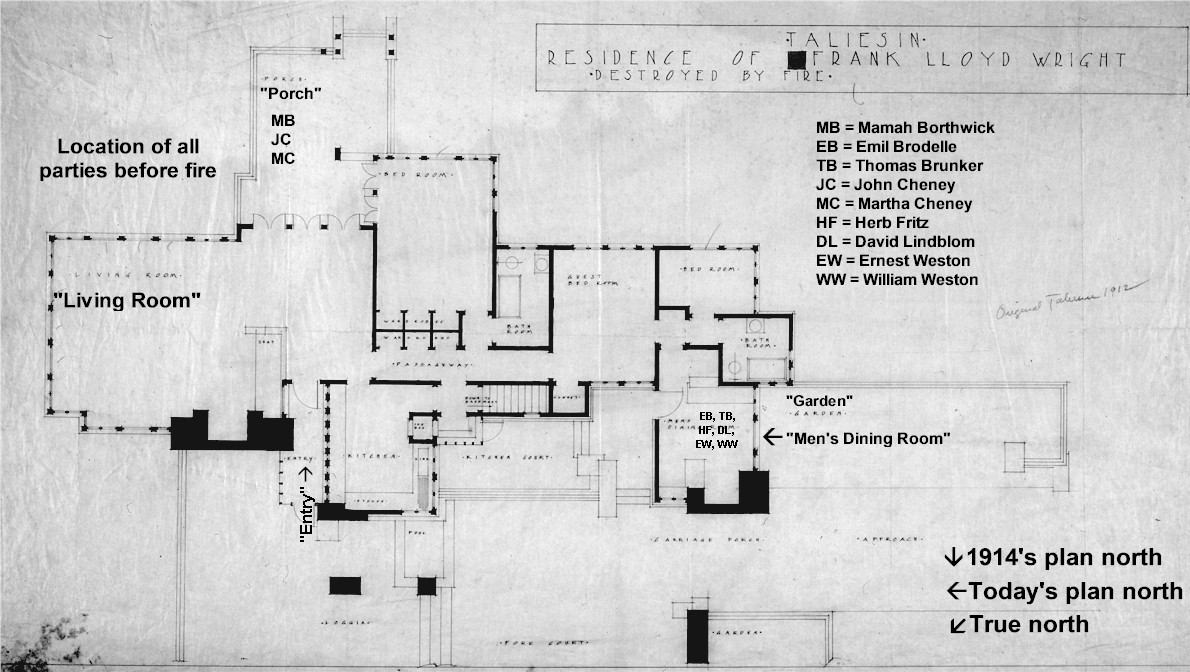

former wife of Edwin H. Cheney, and the woman for whom Wright first designed Taliesin south of Spring Green, Wisconsin. And who was murdered on August 15, 1914.

Since Mamah’s birthday is June 19, I am addressing this question in this post.1

Or “pondering” I guess. Since this is all my opinion. Did you ever think it wasn’t? Well, I didn’t, I can tell you that.

Plus, I’ve no idea what Wright would have thought or felt about this

even though I so wish that he was interested—beyond the grave—on my thoughts about things.

But, really:

was Mamah Borthwick the love of Wright’s life?

Determining who was “the love of” someone’s life is kind of like determining who someone’s “soulmate” is. Altho, dammit, the press continuously referred to Frank Lloyd Wright and Mamah as “soulmates”!

As for those two

I think they loved each other terribly. I’ll bet it was the out-of-your-mind crazy love. Of course, tempered by the fact that they were both married with children. Which came with a lot of excitement because they lived in Oak Park and everyone would know if they were fooling around.

And

if Wright had also been murdered at Taliesin in 1914, I think Mamah would have been counted as the love of his life. Which you can definitely say for her. You can see that especially when you look at research in Mark Borthwick’s book:

A Brave and Lovely Woman: Mamah Borthwick and Frank Lloyd Wright.

Distant cousin Mark Borthwick detailed how Edwin H. Cheney pursued Mamah for years. From what Mark Borthwick explored, it’s not certain that Mamah thought of ever marrying before becoming Mrs. Edwin H. Cheney in 1899. Mark Borthwick wrote:

Apparently sober, constant, and determined, to judge by his years-long courtship of Borthwick, [Edwin Cheney] lacked the vivacious spark she herself nurtured…. Probably none of the men in her class measured up to her standard, but she no longer had the luxury of time.

A Brave and Lovely Woman: Mamah Borthwick and Frank Lloyd Wright, by Mark Borthwick (University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 2023), 60.

In addition, when the press found Wright and Borthwick at Taliesin, Wright confessed that he and his then-wife Catherine were too young when they married.

Ok,

as for that choice: aside from the fact that everyone told them not to get married that young, they were in love, it was the 1880s, and it’s not like they were the only people to ever do that. After all, “Marry in haste and repent in leisure” was put into writing almost 500 years ago.

So,

they married in 1889 and Kitty gave birth to their first child in 1890 (Lloyd).

- Then again in 1892 (John).

- And in 1894 (Catherine).

- Then in 1895 (David).

- Then a break and in 1898 (Frances).

- And another break and their youngest in 1903 (Llewellyn).

- Here’s part of what Wright in his Autobiography:

Architecture was my profession. Motherhood became hers.

Fair enough, but it was a division.

The young architect’s studio or workshop was within a few years built on Chicago Avenue. The young mother’s home and kindergarten had continued and still kept on—on Forest Avenue….

The handsome children were well born. They, each and all, were fine specimens of healthy childhood. They were curly-headed, blue-eyed, sunny-haired, fair-skinned like their beautiful mother. They all resembled her.

Every one of them was born, so it seemed, directly in his or her own right. You might think they had all willed it and decided it all themselves.

Frank Lloyd Wright, An Autobiography (Longmans, Green and Company, London, New York, Toronto, 1932), 109.

Then Wright and Mamah got close during the commission of her and Edwin’s house (commissioned in 1903).

So, MAN, Keiran

– you’re dancing around the answer here, aren’t you? Just say what you think: was Mamah the love of Wright’s life?

Here’s my two cents:

I don’t think so.

I don’t think it’s possible to say that someone was the love of a person’s life when they died just after your halfway mark.

Wright met Mamah when he may have just been “going through the motions” in his marriage. Then they flee to Europe, which is followed by all the front-page news when they came back (which just bound them together I’m sure). And three years later, there was the horrible murder in 1914.

And then Wright lived over 44 years more. Therefore, he lived a lot of life after Mamah. I don’t think you can say that a man who continued to create incredible, deeply felt art, was emotionally stilted.

i mean, well yes, the man said and did some things sometimes where it’s like, hmmmm. but…

And I’m not saying Wright didn’t love Mamah. But I think we’re looking for the wrong thing if we point at her and say, “That was it. She was ‘The One.'”

In 1924, after his relationship with Miriam Noel (his second wife who I wrote about recently) rounded to its close, he met Olga Lazovich Milanoff.

Olgivanna was also with him through some extremely difficult times. There’s Taliesin’s second fire; the pursuit following the birth of their daughter, Iovanna; and the years in the latter 1920s with difficulties followed by the Great Depression. And she was with him and brought him to the last part of his life, and revival of his career.

Back to Mamah

As I grow older, I have come to understand that love and relationships are a lot more complicated. I mean, Romeo and Juliet is a great love story when you read it as a freshman in high school, but…

So I’ll end with what I wrote to myself in April 2005.

After the marriage of now-King Charles III to Camilia Parker Bowles (now Queen Camilla):

[Charles] loves a woman, Camilla. He joins the navy (1971-76) and Camilla marries someone else. He can’t ask her to get divorced: it’s the 1970s and he’s still required to find a virgin.

So he finds Diana Spencer. She’s a little unstable. They don’t fit…. and he’s still in love w/Camilla. Diana starts having lots of torrid affairs and vomiting and cutting herself.

I’m saying:

neither party in that marriage was entirely innocent.

And then Diana died….

If I were in his position and my ex-wife, “The People’s Princess” died, seriously, one of the first things I would have thought would have been, “Oh cr*p, now I can’t marry Camilla.”2

Now, at least, he gets to marry her, which from what I’ve heard, is what he wanted 35 years ago.

To me, in the end, this is actually a very romantic story, about 2 people who loved each other and now finally get to be together, formally, in the eyes of the world….

They still hang out and do stuff. Presumably, they still make each other happy.

That is one cool story, if you ask me.

And that’s what I’ll say. Mamah Borthwick was a love of Wright’s life.

First published June 14, 2023.

The image at the top of this post was published in the Chicago Day Book, December 21, 1911. It’s available at this link.3

Notes:

1. She was born in 1869.

2. Or “oh bloody hell,” because I’m Prince (now King) Charles and not a dirty commoner.

3. I changed my original image from the front page of the Ogden Standard, which was a story published after Taliesin’s 1914 fire/murders on September 5 (find it here). That’s because I learned that the woman in the photo on that page is not Mamah Borthwick. The photograph shows Catherine Wright, his wife at that time. Thanks to Allen Hazard for correcting me.

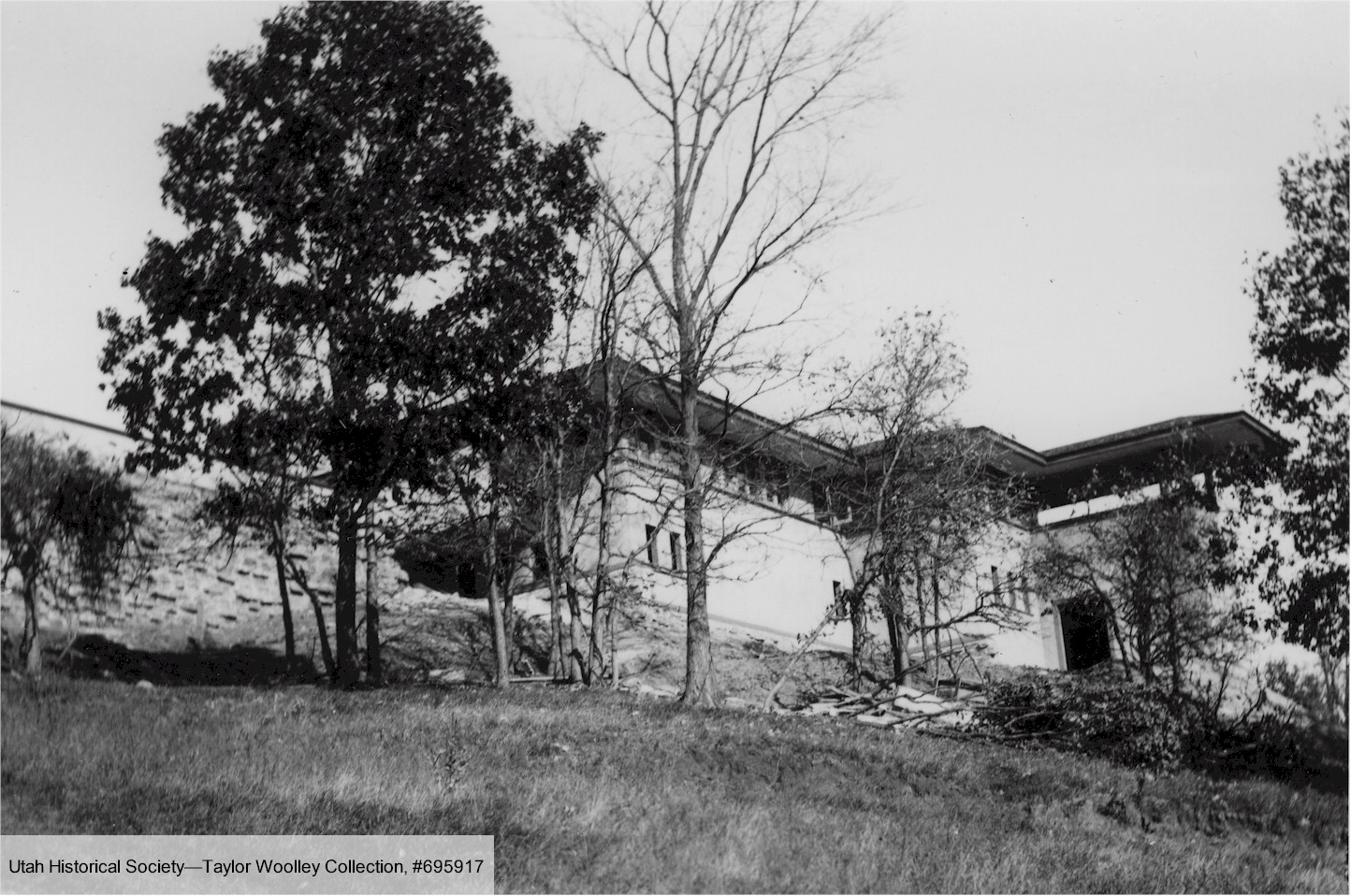

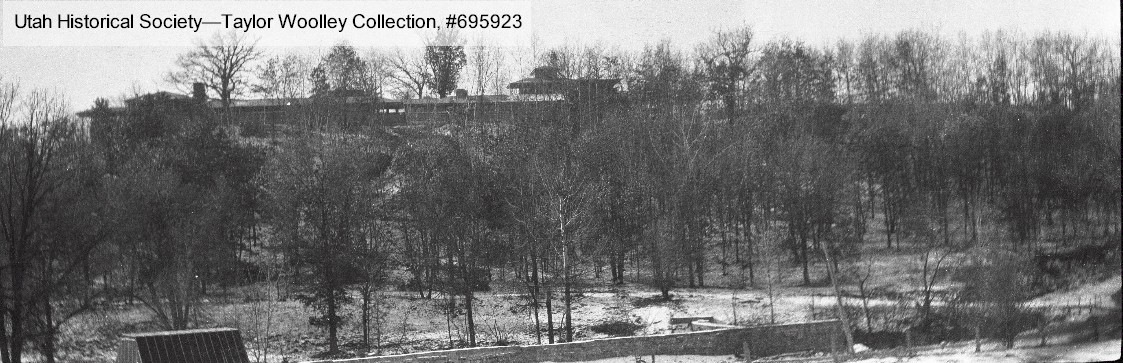

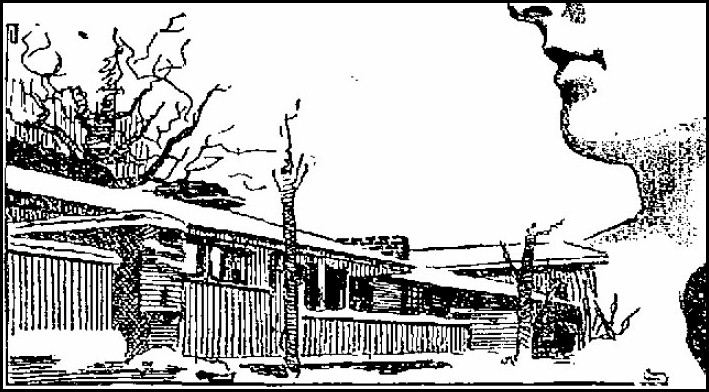

You walk up the steps at Taliesin to Wright’s studio at Taliesin (the north wall of the studio is to the right). The parapet from the Taliesin I photo ended at the stone that is to the left of the tree trunk (the tree trunk is to the left of the window that’s on the extreme right in the photograph) .

You walk up the steps at Taliesin to Wright’s studio at Taliesin (the north wall of the studio is to the right). The parapet from the Taliesin I photo ended at the stone that is to the left of the tree trunk (the tree trunk is to the left of the window that’s on the extreme right in the photograph) .