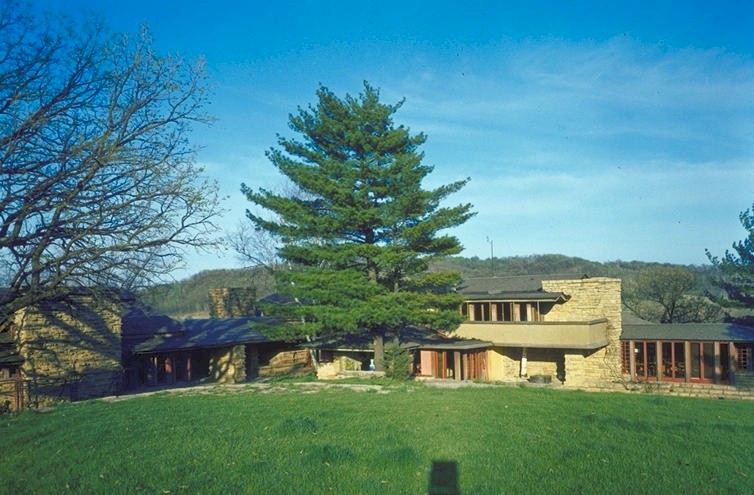

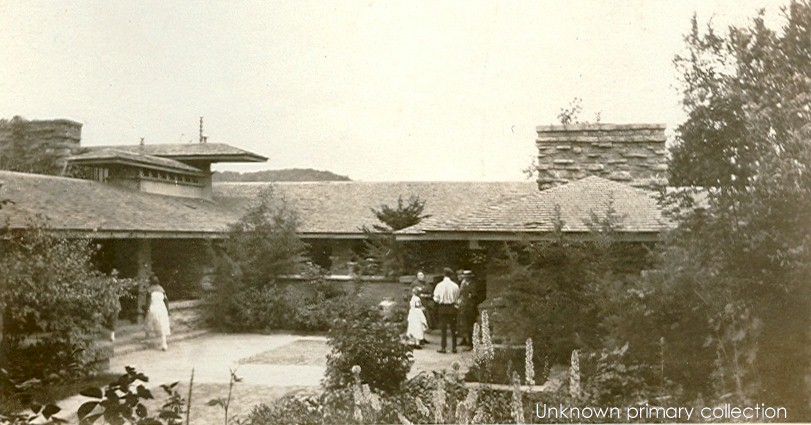

I took this photograph in 1994 under the oak tree at the Taliesin Tea Circle. The room with the French doors near the center of the photograph is Taliesin’s drafting studio. Wright used it as an office after he moved drafting operations to Hillside.

“1867. . . . 1886. . . . 1896. . . Oh, shit – 1901? 1902?”

That’s basically a transcription of what came out of my mouth in 1994 while I drove with Alex1 from Madison, Wisconsin to Spring Green and the Taliesin estate. The dates were important in Frank Lloyd Wright’s life and on the Taliesin estate.

The rundown of all those dates

1867: the year Wright was born.

despite how much he lied about the year he was born, which can get you into a rabbit hole on the internet unless you’re judicious

1886: the year Unity Chapel was designed/built.2 It’s the family chapel and can be seen from Taliesin.

1896: the year the Romeo & Juliet Windmill was commissioned by Wright’s aunts.

1901: the year the aunts commissioned Wright for the Hillside Home School stone structure. We were taught 1902 for a while. But, the Weekly Home News (Spring Green’s newspaper) edition of October 1, 1901 said:

“Owing to the increased attendance, the principals [i.e., the Aunts] have decided to build a new school house. The plans have been drawn and sent from the studio of Frank Ll. Wright, architect, Chicago, and work upon the construction will begin at once.”

I recited those dates to continue my obsessive-studying over the previous week. Alex and I were newly hired tour guides. He and I knew each other because we were students at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (he studied Architectural History and I was pursuing my Master’s degree in Art History3).

On that day in the car, however, I had no idea that I would become an expert on Taliesin, and would eventually live in the village of Spring Green.

More about tours:

At that time, Hillside tours were the first ones that all guides learned. An hour long, they gave the basics on Wright’s life and work while going through Hillside’s 14,000+ square feet. Meanwhile, Taliesin House tours were new. They’d only been offered three days a week the season before this. In 1994, they went out 2 times a day, every day but Wednesday. The tours were twice as long as Hillsides, and cost more than four times as much ($35 vs. $8 / $4 for children under 12 4).

Hillside tours were also the most popular. Apparently, one year over 30,000 people took one. Also, there was an architecture firm in the Hillside building, where apprentices at the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture worked in the Hillside Drafting Studio.5

Those at the school were literally apprentices working under the licensed architects. Later, the firm closed and the curriculum changed so they became actual students.

Lastly, there was an exterior Walking Tour created in ’86 or so. Before the House tour existed, the Walking Tour was the closest a person could get to Wright’s residence. And that was only while standing at the bottom of the hill around which Taliesin sits.

That summer:

Here are a couple of my Taliesin-related memories from 1994:

The first time I got a laugh on tour. It was when we came up to the exterior roof of the Hillside Theater foyer. Its ceiling rises to just about 6 feet tall. As I brought the group to the foyer, I gave the story I’d been told: that, “Wright always said that ‘People over 6 feet tall are wasted space.'”

Running through a Taliesin courtyard as birds fluttered by me, and chuckling while I thought, “what I did on my summer vacation.”

An interesting group of people

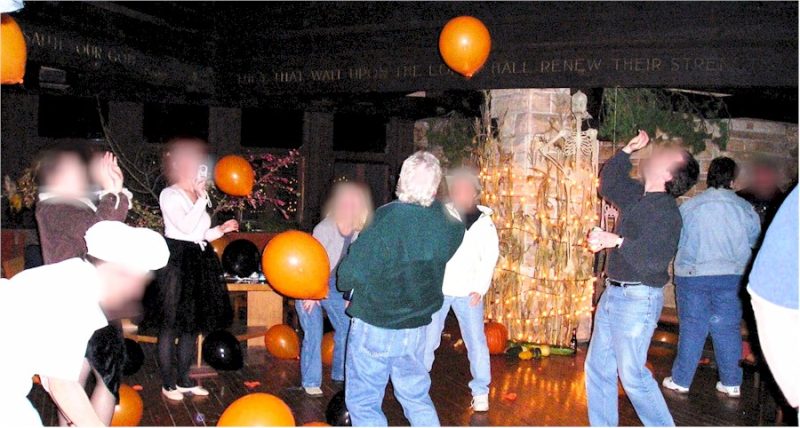

I remember laughing hysterically that summer with those funny, smart people. In fact, most of the people that I’ve encountered at Taliesin through 25+ years were whip-smart and creative, along with being devoted to Wright and his architecture. Another reason to stick around. Here’s a photograph of some from an end-of-the-season party one year at Hillside:

As the buildings were (or are) unheated, closing down the structures commenced in the days after the season’s end. So, having a party allowed the staff to let off steam and prepare for the upcoming work. Plus, most of the staff wouldn’t see each other again until the following spring. Wright’s living quarters are heated now, but not Hillside. That still has to be prepped for Wisconsin winters. Unlike earlier years, the people who now close the buildings are the Preservation Crew.

Plus, my movie-viewing experience expanded:6

Alex and I were invited that summer to watch movies at the home of a Senior guide (who officiated my wedding 23 years later). He showed us The Last Picture Show, The Magnificent Ambersons, and Evil Dead, Part 2, among others I’m sure I’ve missed.

Craig also figured out how to hook the History geek into the Wright world.

uh… that’s me.

So, when a “House Guard” went on vacation, he put me on the schedule with the other guard, Germaine. Germaine, whose father was Wright’s gardener, became friends with Iovanna (the daughter of Frank Lloyd Wright and Olgivanna). Germaine, this elegant older woman, who always wore dresses and her hair in a chignon, spent years in the Taliesin Fellowship and later married apprentice Rowan Maiden.

House Guards (now known as House Stewards) opened the House in the morning, by cleaning and vacuuming. They, then and now, greet people at Taliesin’s front door and, at that time, gave out booties for guests to put on their shoes.

Booties were used to protect the rugs. I guess they do, but maybe not when thousands of feet walk over the rugs every tour season. The booty fuzz—a light blue—gets all over the rugs. You almost have to use your fingernails to scrape it up.

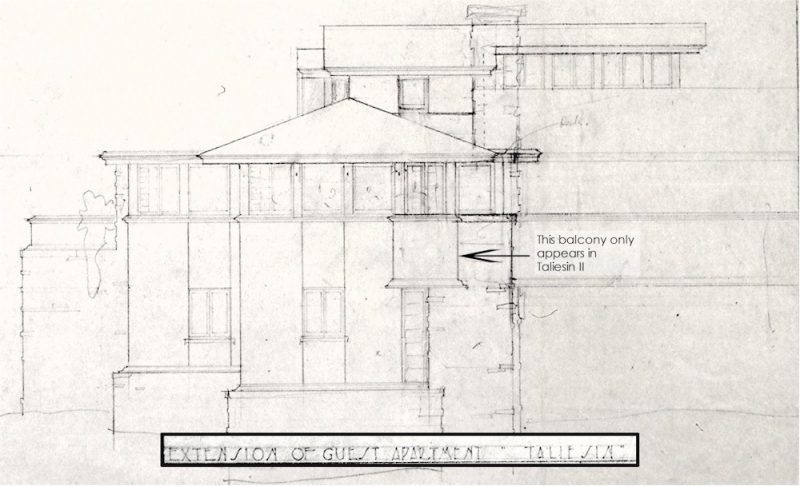

Germaine and I had time to talk that week. She told stories of the life at Taliesin and invited me up to Iovanna’s5 bedroom (in the floor above Frank Lloyd Wright and Olgivanna’s quarters). That’s when she told me that she and Iovanna used to sunbathe outside on a little balcony.

I mentioned this in the on-line presentation I gave in 2020 through The Monona Terrace Community and Convention Center.

Another memory

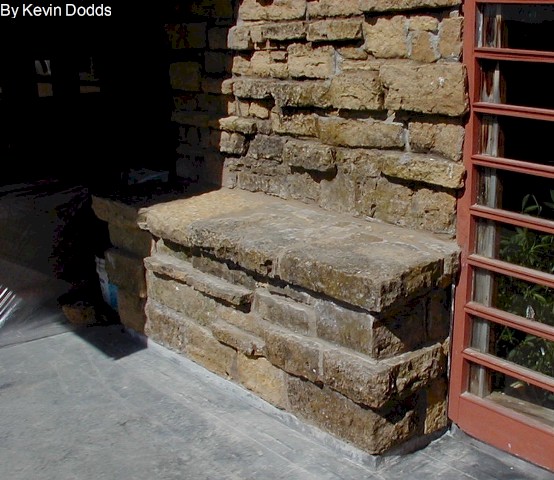

Photograph of the Taliesin Tea Circle with the oak tree. The Chinese bell is hanging off the limb veering to the left.

I remember sitting in the Entry Foyer at Taliesin’s “front” door, waiting for a House tour. A member of the Taliesin Fellowship, architect Charles Montooth, came bounding up the steps of Taliesin’s Tea Circle on break (he usually worked at the Hillside drafting studio). He ran up to the large Chinese bell that hung from the oak tree limb you see in the photo above, then stopped in front of it and drummed it several times with his knuckles. He paused for a moment to listen to its faint ring, then ran back down to where he came out.

Taliesin tours certainly struck me,

as someone who had measured my worth mostly through test scores, as a very nice way to come into adulthood. Plus, giving tours meant that I was judged for the words that came out of my mouth instead of numbers on a page.

You can read here how the tour program became integrated into my life.

First published March 7, 2022.

I took both of the photographs used in this blog post.

1. not his real name

2. We also thought 1886 was the year he designed the first Hillside Home School building for his aunts, a.k.a., the “Home Building“. That was, until being corrected by someone else. The year he designed the Home Building is actually 1887.

3. I received my degree that December with my thesis on David Wojnarowicz.

4. No kids under that age were allowed on tours going into Wright’s Living Quarters at the House. Now tours take kids as young as 10 years old.

5. Now The School of Architecture, no longer at Taliesin.

6. I’m not talking about the biweekly online series, “Welcome to the Basement“.