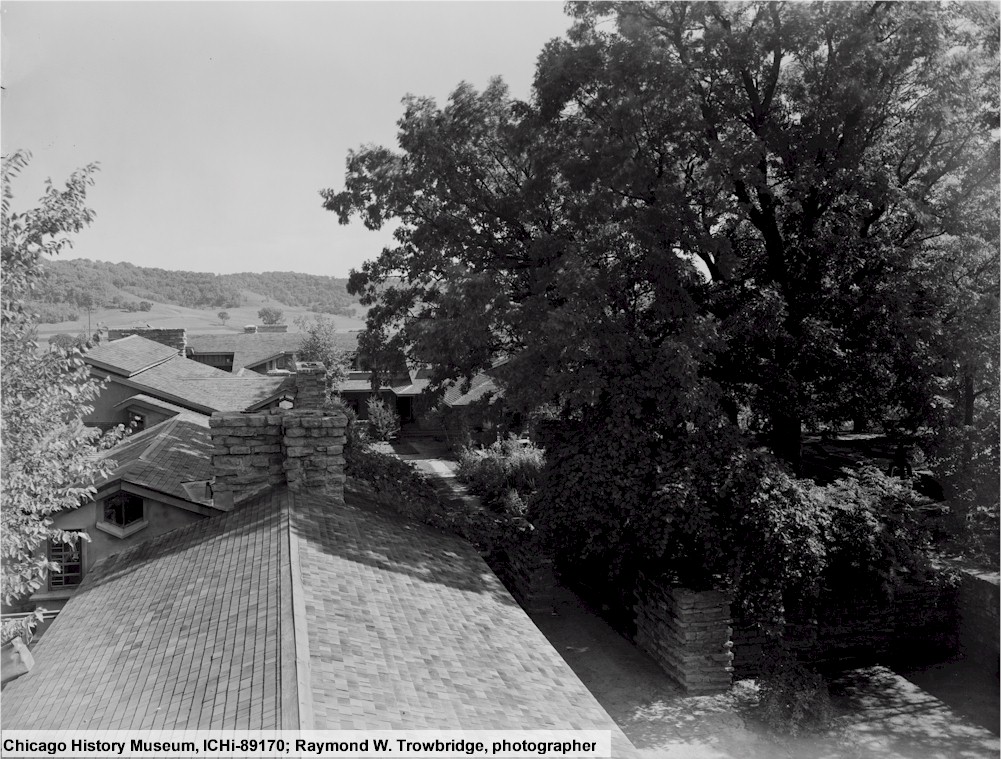

Theodore Farrington took this photograph of a young Frank Wright in Macgregor, Iowa. The Wrights lived there from 1871 until 1873.

As June 8 approaches, it’s time for

the annual performance of:

“When and Where was Frank Lloyd Wright born”

So, I’ve got you covered on “when”. I wrote about that several years ago in this very little electronic space: “Keiran: Don’t Try to Correct the Internet“

The short story is that he was born in 1867

or to make the SEO happy (with active verbs), I’ll write, “Anna Lloyd Wright gave birth to her son Frank in…”

And you can read the post to learn more.

But the other question is:

Where was he born?

Well, we definitely know it was in Wisconsin.

The location of the piece of ground on which he was born though? That’s where things get tricky.

First of all, there’s no birth certificate

(so I can’t even tell you if he was born Frank Lloyd Wright; or Frank Lincoln Wright, which biographer Brendan Gill put forth in his Wright biography1 and while it’s logical, there’s no written proof; thanks, Gill)

You see, when Frank Lloyd Wright was born on June 8, his father, William C. Wright, was working as a minister in Richland Center, 20 miles (32 km) from Spring Green. And the Wrights lived on Church Street in RC, which makes some conclude that Wright was born in the house on that street.

That would seem logical except:

Twylah Kepler, Richland Center historian, told the Chicago Tribune in the year 2000 that shortly after Wright’s birth, Wm. Wright performed a funeral service in Bear Valley, 14 miles (22.5 km) from Richland Center, for someone in his congregation. Since Anna was heavily pregnant at that time, it seems likely she stayed near her husband.

And fortunately for the Wrights, Wm. Wright’s former in-laws, the Holcombs, already lived in Bear Valley. In addition, historian Jack Holzhueter explained to me that it makes sense that Anna would have been ensconced in the house of the in-laws. Since Wm. Wright had the three children from his first (deceased) wife, Permelia, the in-laws could have taken care of the children, and Anna, during her “lying-in” (after all, it was her first child, and they were family).

On the other hand,

The late Wright historian William Marlin wrote that he discovered Wright was born on Church Street. This is part of the article in the Chicago Tribune in 2000:

Marlin wrote a long letter about this birthplace research to Margaret Scott, the resident Richland Center historian at the time. Both have since died.

Marlin told Scott his research led him to believe the home on Church Street is the most likely birthplace, and outlined why in several pages. He… said only new evidence would answer the question for sure.

Jack Holzhueter,… said Marlin’s letter prompted more research into the Church Street house. Instead of bolstering the possibility the town finally had its birthplace, that research cast new doubt on the site.

“I don’t know that we will ever find a Rosetta Stone,” Holzhueter said.2

Marlin died in 1994. His work on Wright’s biography was one of those things I came across that taught me a lot.

I didn’t learn from what Marlin wrote; I’ve never seen that. But I’ve seen the photographs he collected.

See

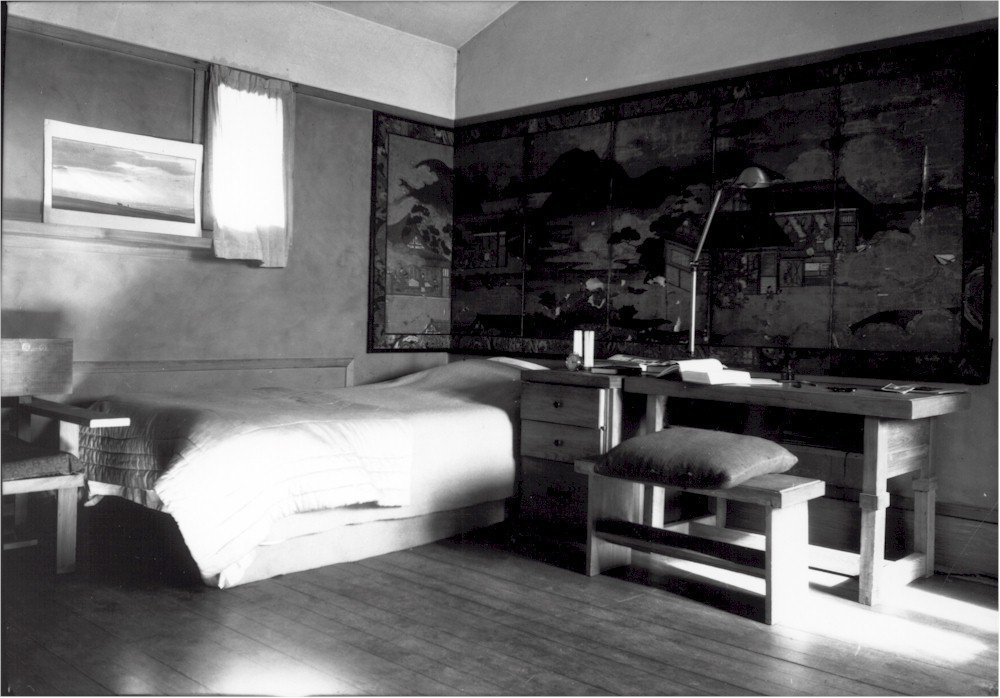

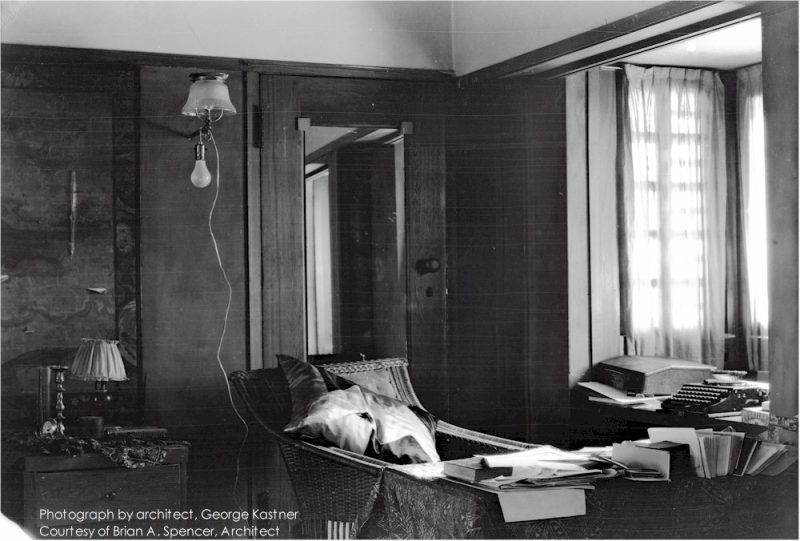

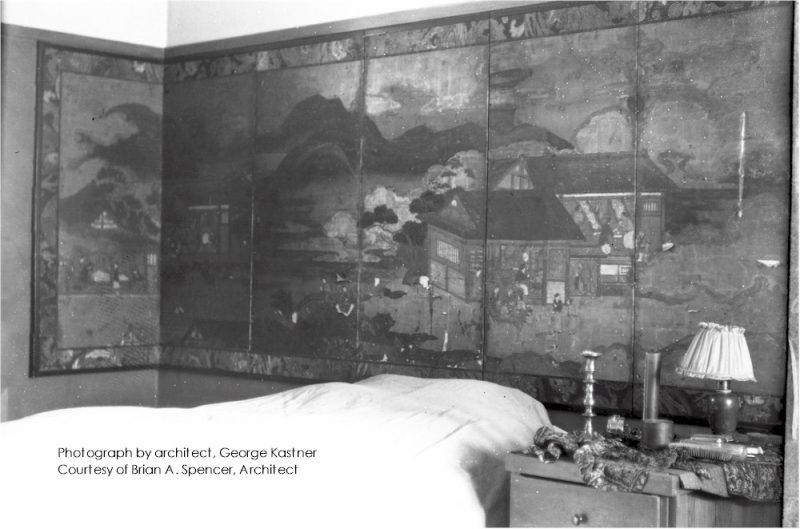

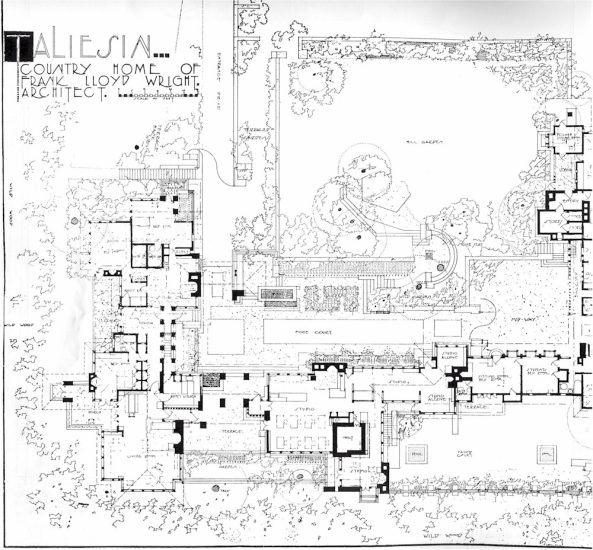

Marlin had been writing a highly anticipated biography on Wright. So he gathered hundreds of photos. And for reasons I don’t know, his photos came through the Preservation Office at Taliesin about 30 years ago.

I also don’t know how long Marlin had been working on his book, but he had collected copies of dozens of photographs from:

• the Pedro E. Guerrero Archives,

• Wisconsin Historical Society,

• Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives,

• the Capital Times,

• and others I’ve never figured out.

Eventually I grew to hate Marlin while working on figuring out the photographs. While they showed only things at Taliesin, they came with no organization, and I had no idea what time frame or even space that I was looking at.

What happened, I think, is that the origin of the images (which I’m sure he kept somewhere) was separated from the key to them.

Although, the information on where he got the images might have just been kept in his head.

In that case, yeah I do blame him.

At least he wasn’t that guy with hundreds of millions of dollars in bitcoin that he can’t get to because he lost the password

So the photos from Marlin were good because they made me look at the details to figure out things on my own.

Like I wrote in “My Dam History” where a winter of staring at bad xeroxes of Taliesin taught me to closely look at photos.

For information

on the puzzle about Wright’s birthplace, read “Frank Lloyd Wright Was Born Here” from the Chicago Tribune published on May 25 2000.

Posted: June 1, 2024

The Wisconsin Historical Society has the photograph at the top of this page, here.

Notes:

1. Brendan Gill. Many Masks: A Life of Frank Lloyd Wright (G P Putnam’s Sons, New York, 1987), 25.

2. as an aside, Jack apparently likes referring to the Rosetta Stone when discussing Wrightiana. He said the same thing when The Album of early Taliesin photographs was auctioned in 2005.