I was working on my Taliesin Book1 and thought up another change at Taliesin I should write about.

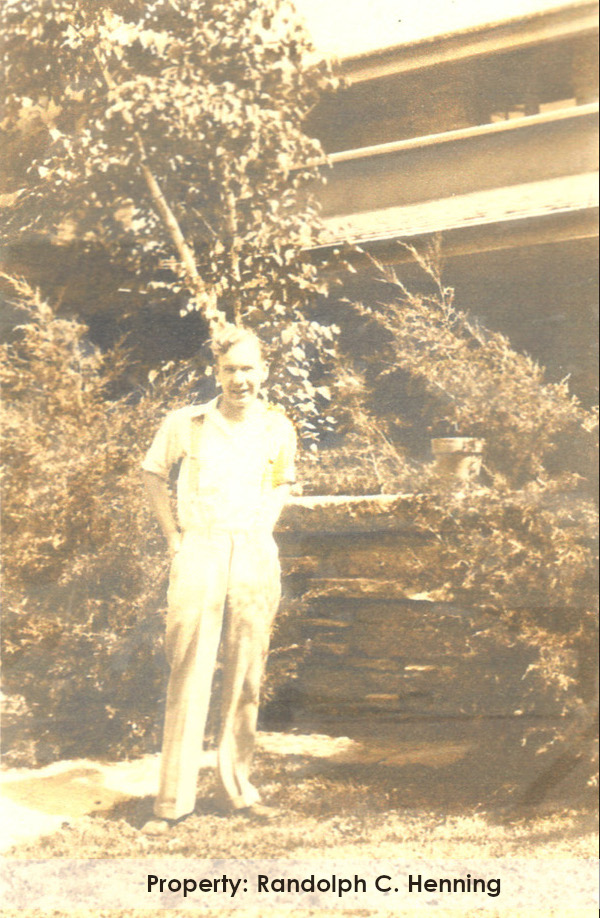

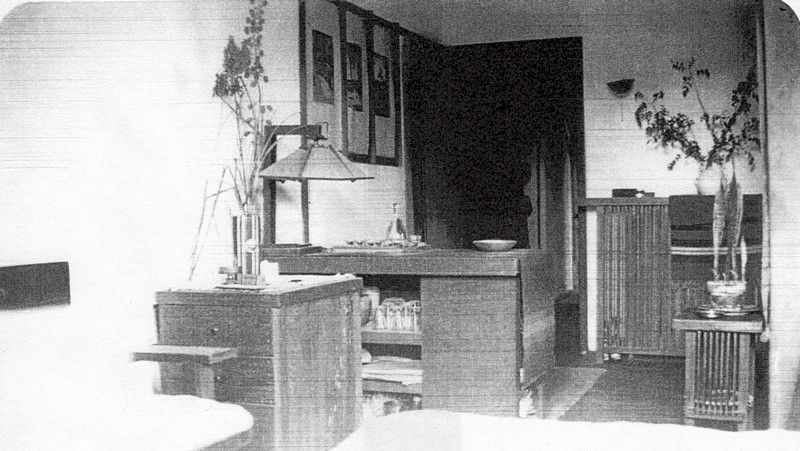

So today I’m going to write about what you see in the photo at the top of this post.

The photo shows

a stairway that used to take you from Taliesin’s Guest Wing (the first floor) up to its main floor, where the Wrights lived. If you popped through the black rectangle in the photo, you’d be in Taliesin’s Entry Foyer (below), about where the black outline is on the floor.2

Finding that stairway was always a wild moment for people. To start with, you’d be on the first floor (which most tour guides aren’t casually allowed into), and be poking around the rooms (by invitation of course).

On the side of the hallway opposite the rooms, about halfway down, you’d see wooden doors covering up an alcove. If you opened them you’d see a couple of steps on one side, and a door-frame with no door. Beyond that, you’d see a stairway that leads nowhere.

This stairway is really old. It might go back to 1911. But if not, part of it definitely goes back to Taliesin II.

In 1911:

to get to these stairs, you’d walk outside to where the kitchen is, and take a right near the current “front door”.

See this post on how to get to the front door in early Taliesin.

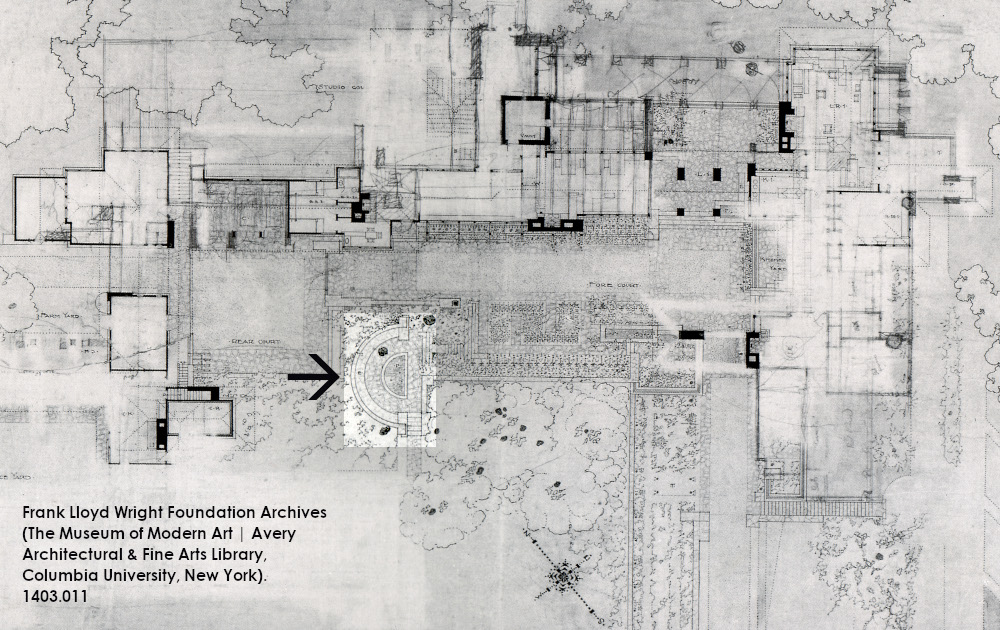

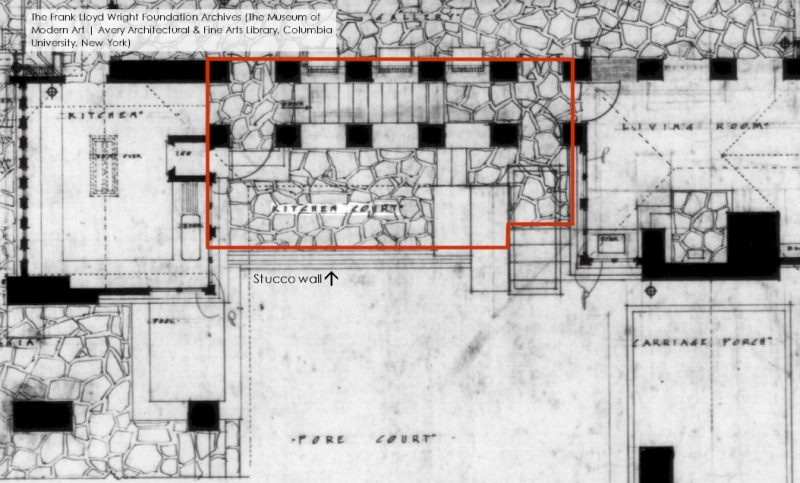

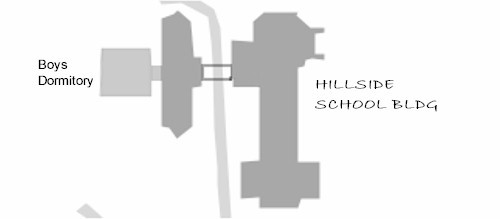

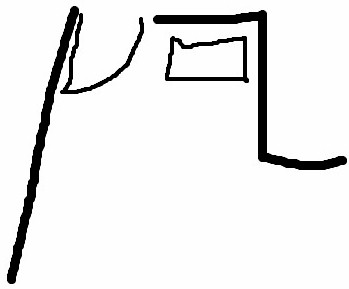

I put a drawing from Wright’s archives below and drew a blue line on the drawing to show you how you’d walk there Taliesin’s Porte-Cochere:

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York), #1104.003.

So, if you walked into Taliesin at that time, you could go through that door, take a step or two, and there was a descending stairway to your right. That was the only way to Taliesin’s first floor for years.

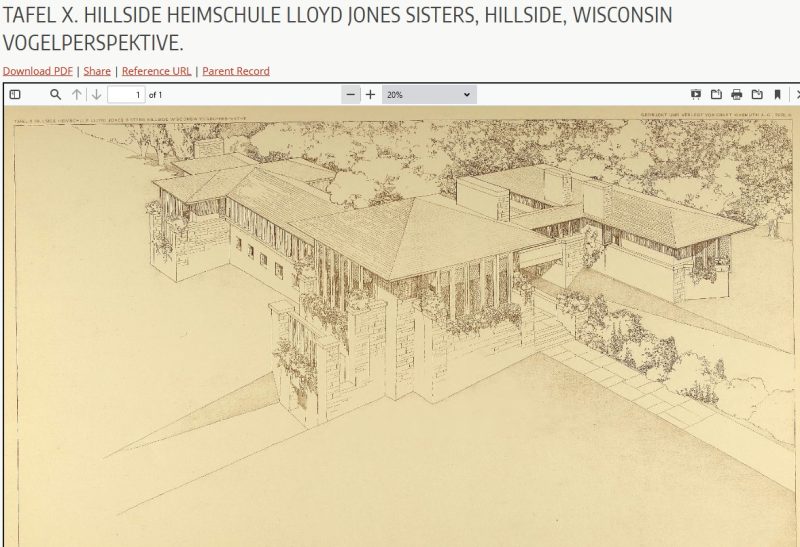

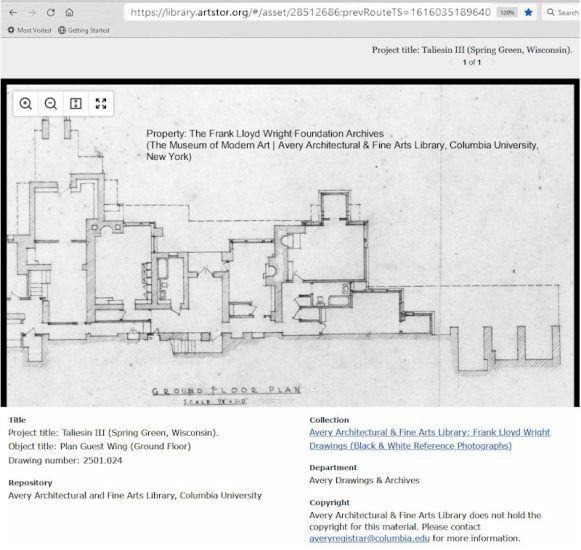

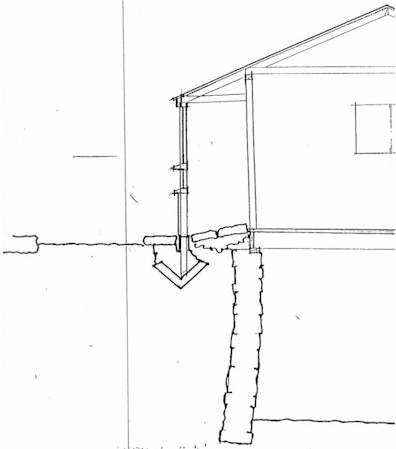

There aren’t any floor plans for Taliesin’s first floor, but you can see the steps in a section drawing I added below:

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York). This is a detail from drawing #1403.013. “1403” refers to Taliesin 2 (1914-1925), but this is Taliesin 1 (1911-14). In the right-hand side of the drawing, you can see plaster in the terrace above the stone foundation. That’s a T1 trait. Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, the late curator of Wright’s archives, didn’t know this and thought for other reasons that this was T2. He had to know a lot about thousands of Frank Lloyd Wright drawings; while I only have to know what’s on the Taliesin estate.

After the first and second fires at Taliesin, Wright kept the steps in the same place. Following Taliesin’s 1925 fire, Wright expanded the descending stairway by about 4 inches.

You could tell that by looking at the stone:

Seven steps on this stairway (from the top down) are red, showing where the fire touched.3 Then there’s a break line on the left, and these yellow steps are undamaged.

The last time

the stairway appeared in that spot in a drawing was the January 1938 edition of Architectural Forum magazine. Here it is, below:

Taliesin’s living room is on the left and Frank Lloyd Wright’s bedroom is on the right (“Master”). Apprentices executed the drawing in the fall of 1937.

If you click

on the link for the Architectural Forum magazine ABOVE, it takes you to the copy of that magazine issue at ARCHIVE.ORG.

when you get there, the floor plan of Taliesin starts after page 4.

It’s kind of dark, but still: it ROCKS.

BACK TO

what I was talking about:

You don’t see those steps today because Wright changed them

starting in 1939.

Here’s what Taliesin Fellow Curtis Besinger wrote about it in his book, Working With Mr. Wright:

Toward the end of the summer [of 1942] Mr. Wright completed a change in the way one entered the guest wing below the house, a change which he had begun in the fall of 1939 when he had had the inside stair closed….

He had a stair built that was outside but under the cover of the roof connecting the house to the studio. This change in the entrance to the guest wing seemed to be in anticipation of the fact that the Fellowship, reduced in numbers, would all be living at Taliesin during the coming winter.

Curtis Besinger. Working with Mr. Wright: What It Was Like (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, 1995), 139.

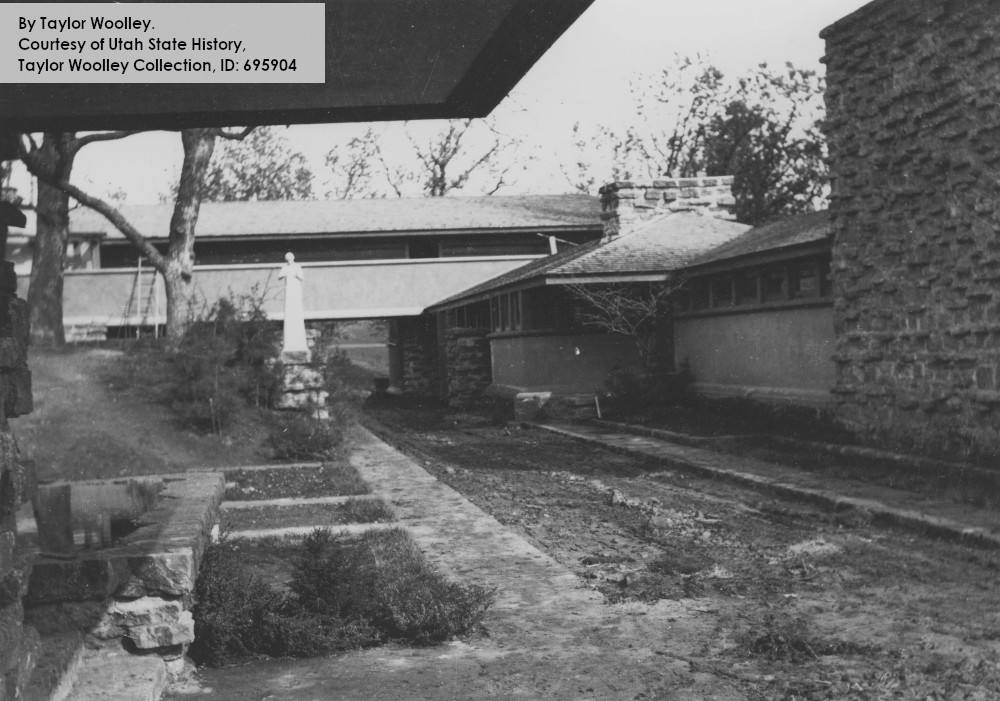

Luckily, his 1939 change appears in a drawing in the book, In the Nature of Materials, 1887-1941: The Buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright, by Henry-Russell Hitchcock:

Apprentices in the Taliesin Fellowship also executed this drawing not currently in Wright’s archives. This drawing is in the book, In the Nature of Materials, figure 271.

But those steps are no longer there, either.

Besinger explained the move in the same passage as above:

Of course this entrance was changed again several years later. It was made into an entrance that was more gracious, less steep, and better lighted.

Besinger, Working with Mr. Wright, 139.

They’re under the roof you see in the 1955 photo by Maynard Parker:

You can see this view if you take a 2-hour Taliesin House tour, or the 4-hour Estate tour.

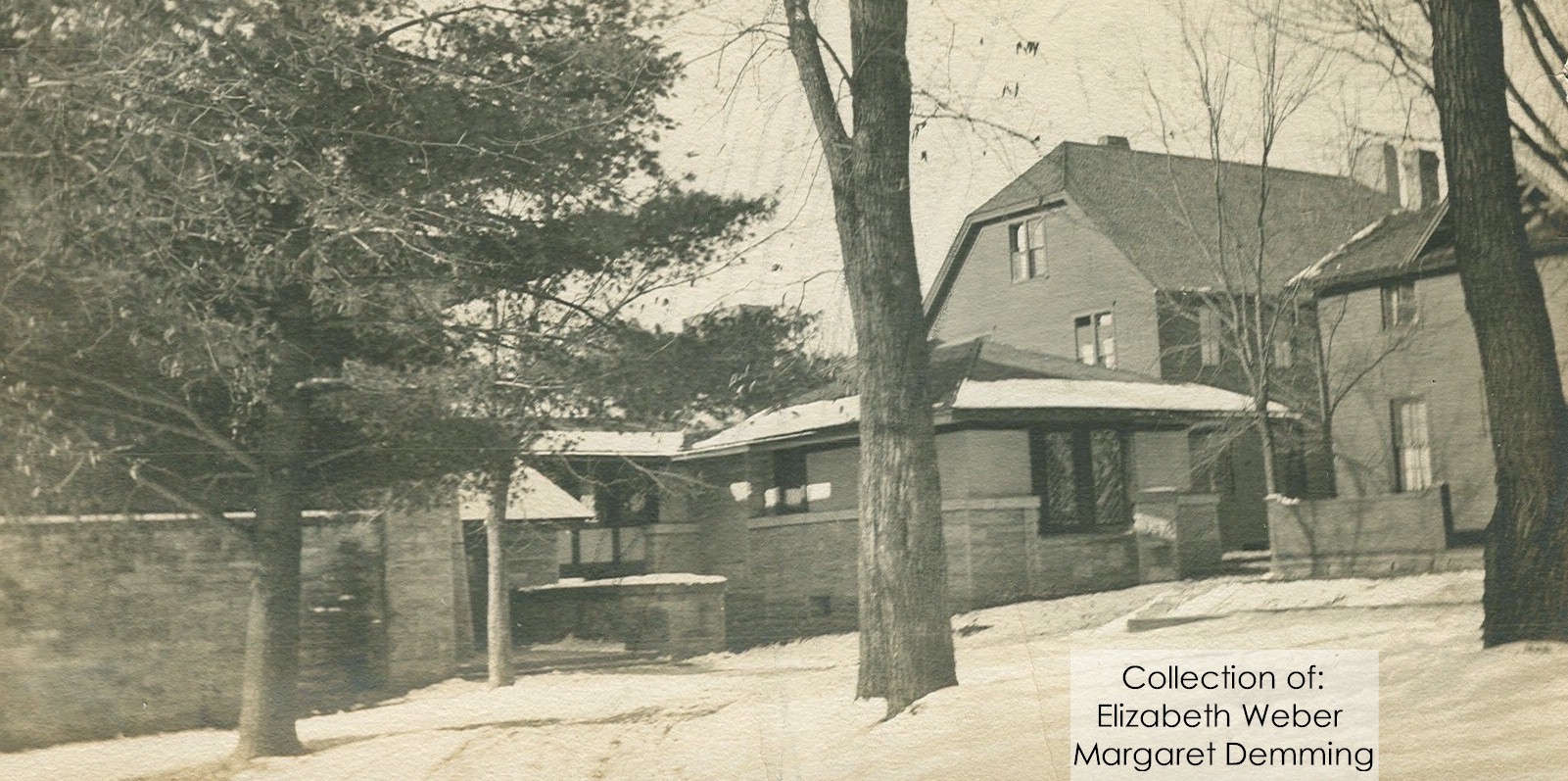

I don’t think I’ve ever seen

a photo from when the steps were in front of the Taliesin kitchen

(the “Little Kitchen”).

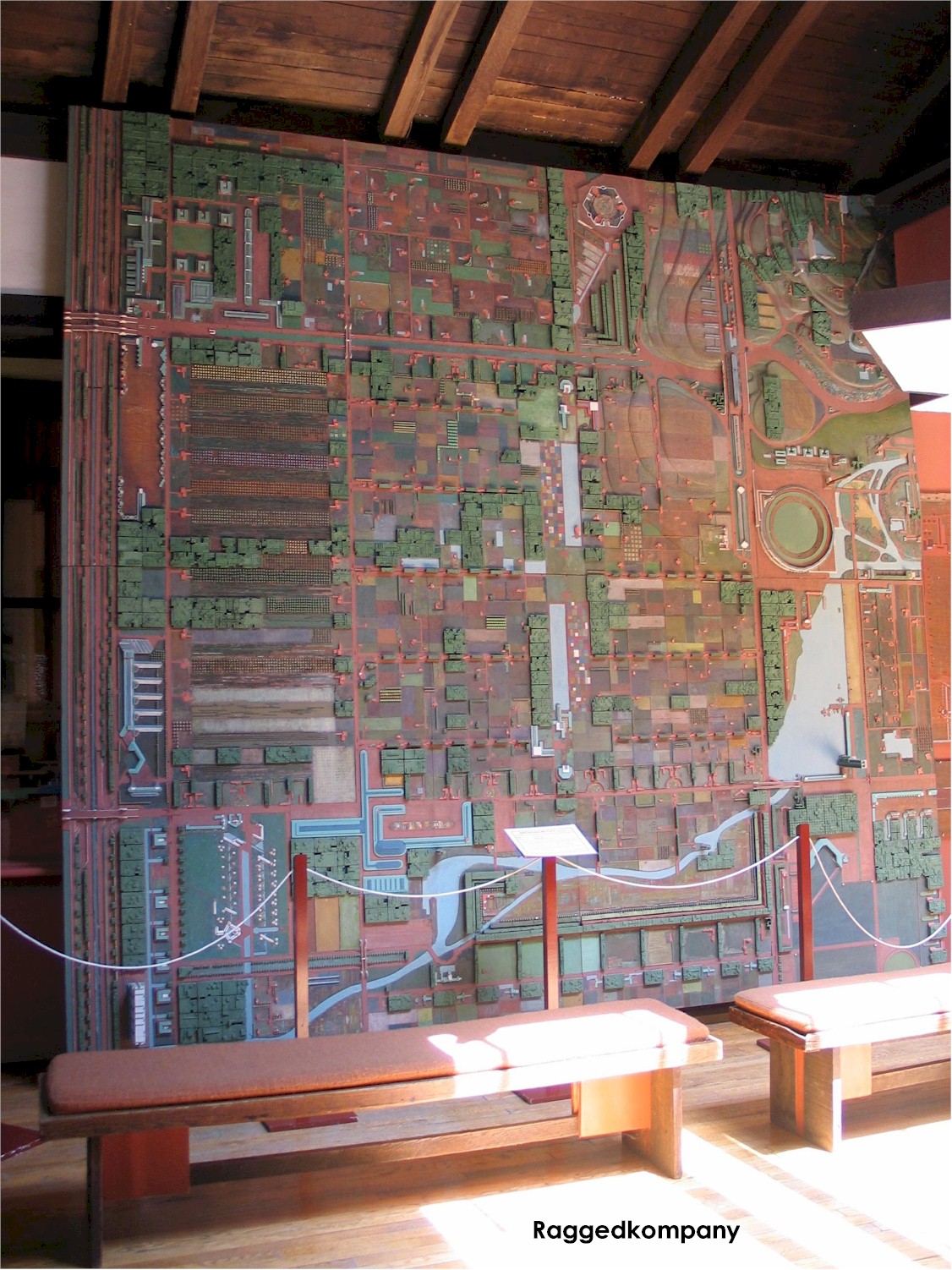

But, like many things at Taliesin, while Wright changed stuff, evidence of it was usually left behind.

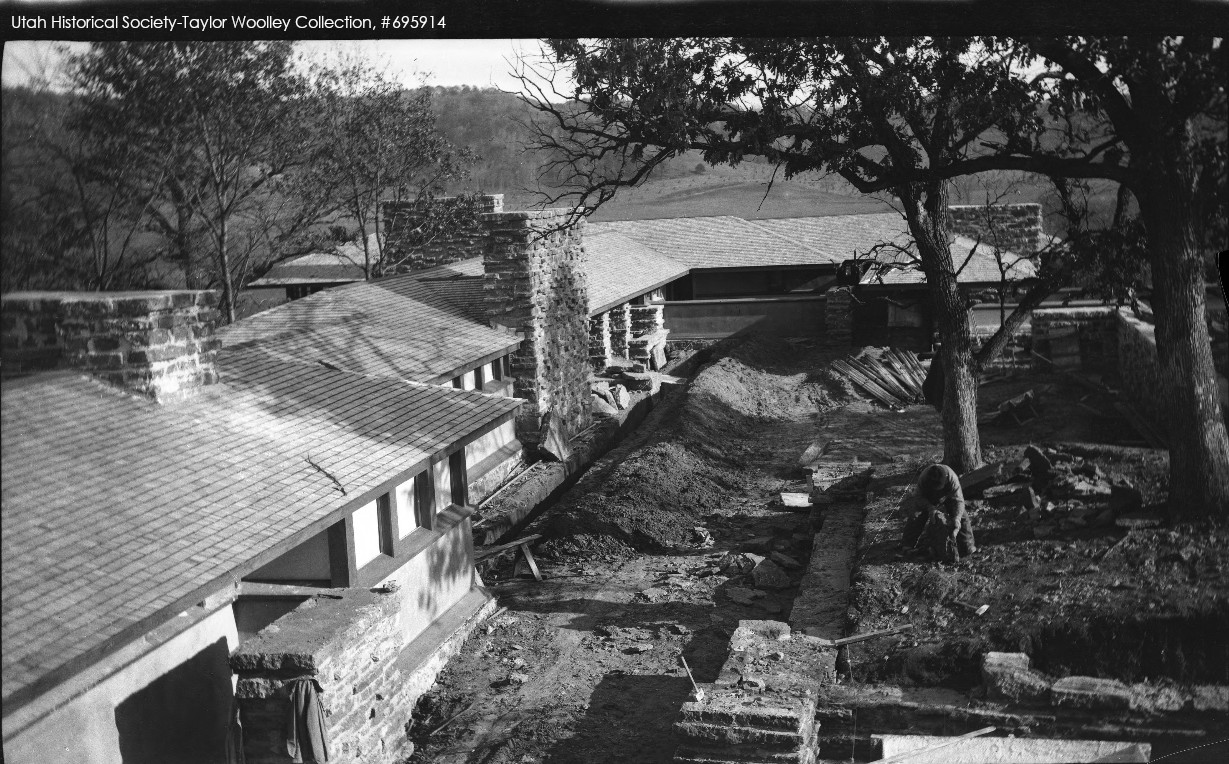

We found this out during Taliesin’s Save America’s Treasures project in 2003-04. The contracted masons were taking the stone out of Taliesin’s Breezeway and it was like, lookey here!

Before:

Looking in Taliesin’s Breezeway at the door to the “Little Kitchen”.

And after:

The Breezeway again. You can see to the edge of what’s been removed, where the top of the steps were revealed.

I’ve written about the SAT’s project before. With the found window, and the found floor—and other things—I should write that down sometime.4

Last thing:

those steps under the main floor are one of those things by Wright that you will only (mostly) be able to experience in your mind.

Because

they are now inaccessible.

The climate control work that the Preservation Crew has done included finding spaces where they could add chases for machinery to adequately heat and cool the building.

In fact, when staff and I went down to the Guest Wing in 2018 to see their work, I asked the Director of Preservation at Taliesin if we could still see them.

He opened the door to the alcove and, on one edge, you could see maybe 4 inches [10.16 cm].

STILL:

I showed a drawing with the steps in my posts about the night that future architect Gertrude Kerbis spent at Taliesin; and when I identified an old photo of the “Blue Room”.

First published November 1, 2024

I took this photo the first day I was taking photographs related to Taliesin’s SAT’s project.

Notes:

- It’s a continual project that I hope to finish one day.

- It was right next to where we found that floor in 2003 during Taliesin’s Save America’s Treasures project. I wrote about that in 2022.

- Read my “I Looked at Stone” post to find out why they’re red.

- I’ll put it into a book entitled, “That’s Not a Crack, That’s a Change: Adventures in Preserving Taliesin”.