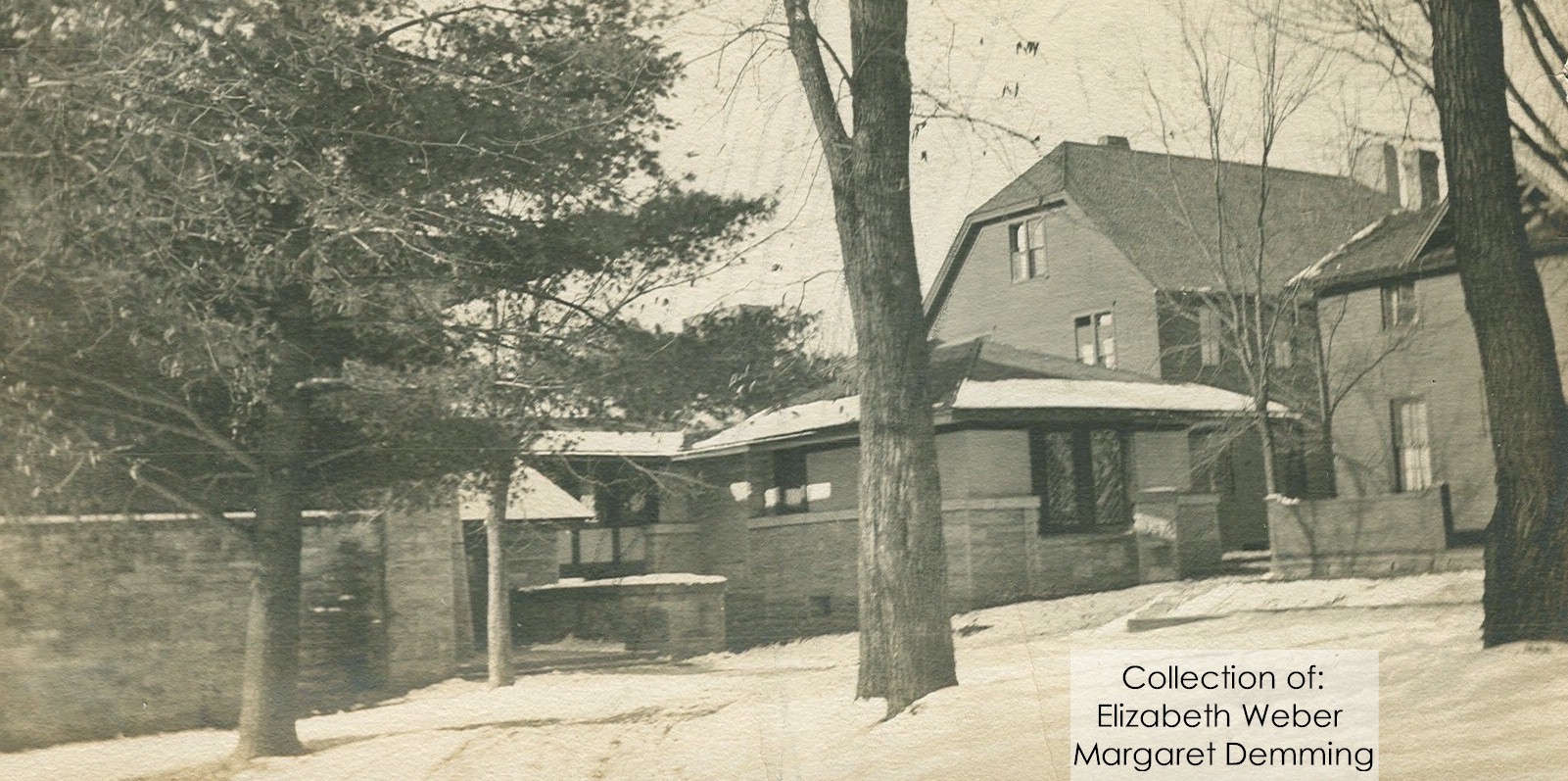

A photograph from 1910-1911 showing three structures on the campus of the Hillside Home School. Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hillside building is on the left and behind it, with the hipped gable roof, is the dormitory for the high school boys. The third structure on the far right was known as the Home Cottage and was for the younger boys.

In my last post I wrote about finding something during the Comprehensive Hillside Chronology. Today, I’m posting about another find made during that project.

Although, I credit this find to my research and writing partner on that project, Anne Biebel (principal, Cornerstone Preservation). She made the mental connection; I only agreed after the surrounding evidence became too strong.

What was this find?

That Wright’s Hillside structure was physically attached to another building that he didn’t design. Literally: Wright connected his building to a wooden, 3-story building right behind it.

Whew – I feel better just coming out and saying that.

How this was found out:

Anne and I looked at the Hillside drawings while researching. At that moment, we weren’t looking at drawings of Wright’s Hillside structure done when Wright first built it for his aunts.

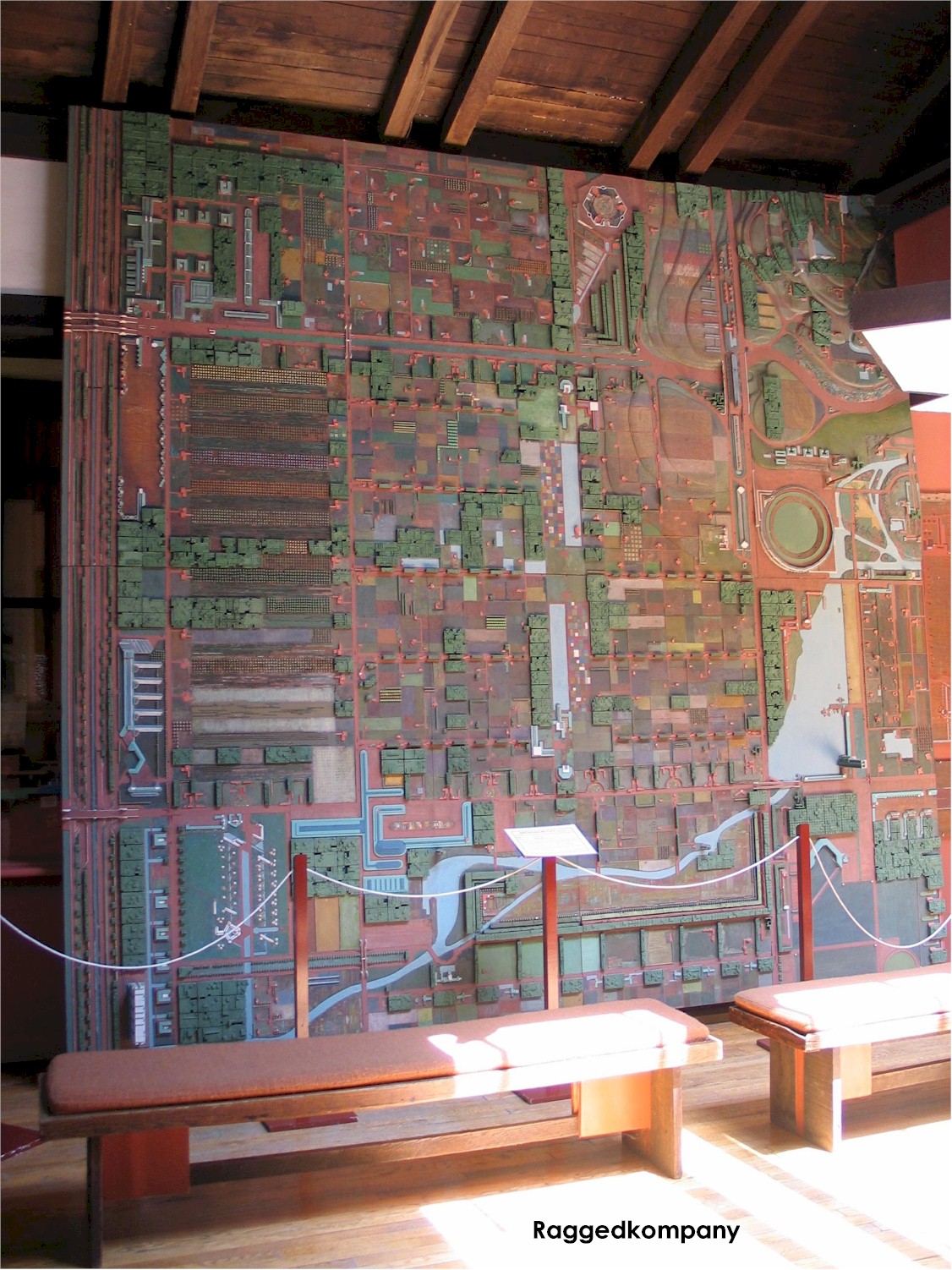

No: we were looking at another drawing, dated November 8, 1920. Wright requested it from a draftsman to show the entire Taliesin estate. We were looking at the draftsman’s copy. 1

Wright’s copy of the drawing had changes he made to it over the decades. His version is at the Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library and is reproduced in b&w here. I showed a bit of it a few months ago when talking about reading correspondence about Midway Barn on the Taliesin estate.

The draftsman who drew it:

That was Rudolph Schindler (1887-1953), an Austrian-born American architect who worked under Wright in the United States and Japan from February 1918 to August 1921. 2

Schindler’s version is interesting

His drawing (in his papers at UC-Santa Barbara) seems to show the buildings as they actually existed. This, compared to Wright’s drawings, in which Wright always seemed to add those things at Taliesin that he wanted to exist.

While I won’t show you Schindler’s drawing, I’ll show you the drawing that I made from his. 3

No: this is (more or less) a good drawing, not the mess I drew you when I posted about figuring out that photograph of the Blue room at Taliesin. I tried to trace what Schindler drew.

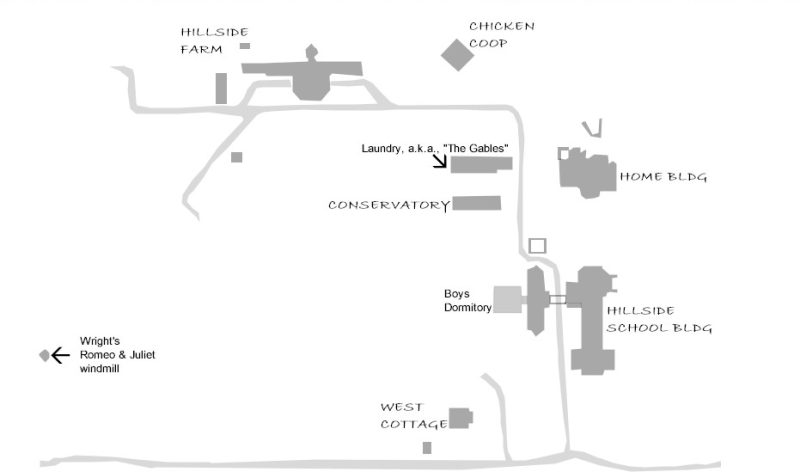

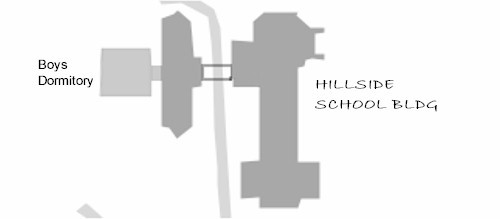

What you see below is my rendition of the part of Schindler’s drawing that shows the campus for the Hillside Home School:

The text in Arial font (like “Laundry…”) identifies buildings that Schindler didn’t label.

Below is that part of Schindler’s drawing that made Anne think Wright’s Hillside building was literally attached to something else.

Schindler just labelled the “Hillside School Bldg”; I added “Boys Dormitory”. But the thing that intrigued Anne was the gray rectangle attached to the right side of the Boys Dormitory. She identified that as a corridor from Wright’s Hillside School building.

By the way, if you’re curious about the open rectangle between the two parts of Wright’s building: that was Schindler’s way of showing that this was a bridge connecting the Science and Arts room to the rest of the structure.

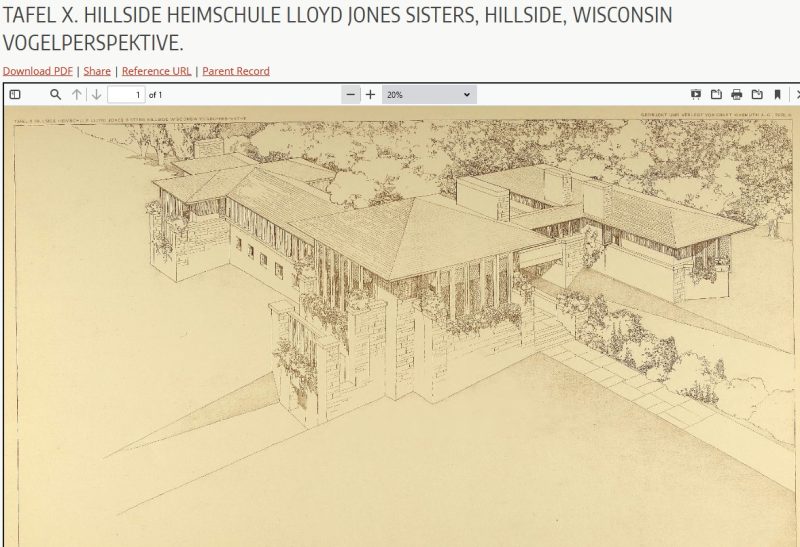

Anne sat across from me while we looked at the drawing and said with excitement that she thought that the Boys Dormitory was attached to Wright’s “Hillside School Bldg”. I totally pooh-poohed it. Besides, another drawing (an aerial, below, done in 1910 for the “Wasmuth” portfolio) doesn’t show anything around the Hillside structure:

The University of Utah

Luckily I wasn’t alone on this project, because

Anne was ultimately proven right:

Over the next few weeks, I kept writing and exploring, looking at drawings with a fine-toothed comb (and probably a loupe). But I noticed things this time. Like,

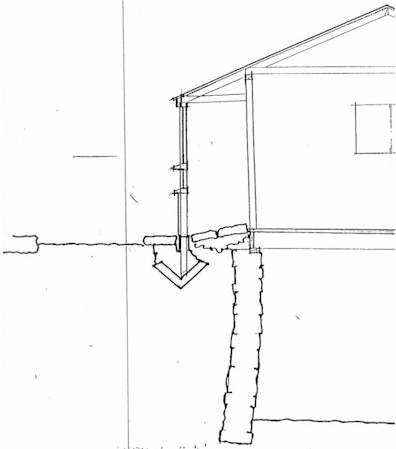

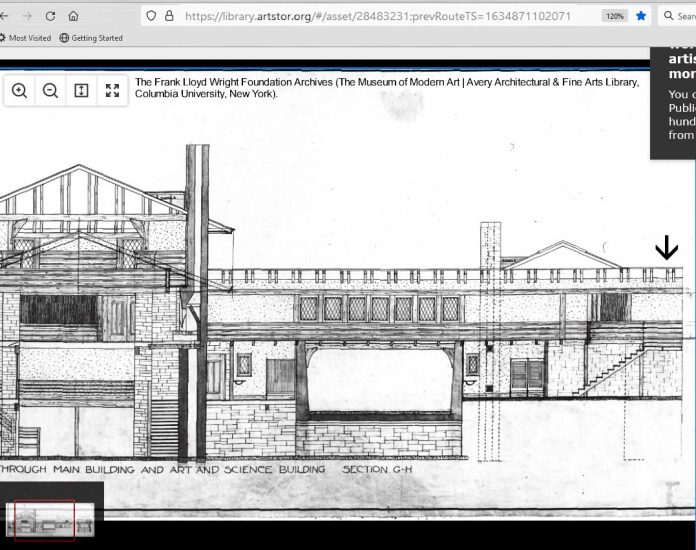

Check out the building section: the building keeps going on the right:

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York), drawing #0216.007.

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York), drawing #0216.007.

The arrow pointing down on the right-hand side is showing—not the end of the building, but—a hallway coming out of it. The hallway that doesn’t really show up in the floor plans or other drawings.

In fact, this find also explained something about the Hillside drawings: there are none of the north side of the Art and Science rooms (the Roberts Room and Dana Gallery). Those rooms are seen in sections, but no Hillside drawing shows what the outside of the building looked like on the north.

Well, I finally started to believe it. Then, I re-read something and found that this very connection was written about –

In a book by a former Hillside teacher:

Mary Ellen Chase (a writer, and educator) wrote about her life as a student and teacher in A Goodly Fellowship. From 1909-1913, the Hillside Home School was her first teaching job. She wrote,

Older boys of high school age had their own homelike dormitory near by [sic]. In 1903 this was connected with an adequate and beautiful school building of native limestone, designed and erected by Frank Lloyd Wright, the son of Anna Lloyd-Jones and a nephew of [the Aunts] Ellen and Jane.

“The Hillside Home School” chapter in A Goodly Fellowship, by Mary Ellen Chase (The Macmillan Company, New York City, 1939), 98.

Then,

we pulled all of the information together (but no photos yet) to support the theory that the gymnasium was attached to Wright’s Hillside building. And that Wright later completely destroyed this connection by the time he started his Taliesin Fellowship in 1932.

Then, early the next year, the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy put out a “Call for Papers” for its 2010 conference (in September). The conference theme was “Modifying Wright’s Buildings and Their Sites: Additions, Subtractions, Adjacencies”. After consulting with Anne, I submitted a conference proposal to give a presentation on our find (Anne was fine with me giving the presentation).

Later, she and I were asked to turn the presentation into an article for a book. So, we worked on the article, still with no photographic proof that the buildings were connected.

Then, lo and behold,

In February of 2011, an album of photographs of Hillside in 1906 appeared (also mentioned in my last post). One of them showed the Boys dormitory, with the hallway terminating into it.

And, finally,

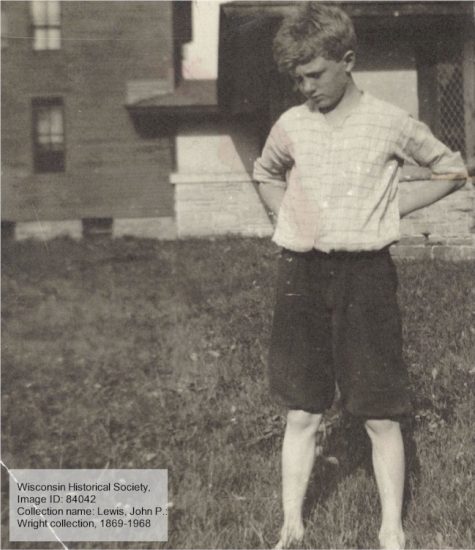

In March or April, 2011, as Anne and I worked on the article in the book, we went to the Wisconsin Historical Society Archives. We opened a folder of photographs in the John P. Lewis collection and—SCORE!—there was a beautiful photo showing that hallway more clearly. That’s below.

Image ID: 84042

That boy is standing just west of the Boys Dormitory and Wright’s Hillside building. The Science Room (now the Dana Gallery) is behind him.

BOOYAH!

Originally posted, February 19, 2022.

A student at the Hillside Home School (class of 1911) took the photograph at the top of this post. In 2005, her daughters, Elizabeth Weber and Margaret Deming, came into the Frank Lloyd Wright Visitor Center to take a tour, giving us the chance to scan the photographs that their mother had taken while she was a student. I asked Elizabeth Weber’s permission to publish the photograph (which appears in the book in which Anne and I wrote the article).

See? Another example of “Preservation by Distribution“!

1. Wright scholar, Kathryn Smith, might have alerted the Preservation Crew about Schindler’s drawing, and got us a photograph of it. Why did she let us know this—and also alert us to the Taliesin photographs by Raymond Trowbridge?—Preservation by distribution.

2. Email from Kathryn Smith to me, January 8, 2021. This information came from her book, SCHINDLER HOUSE, Abrams, 2001, p. 11-16.

3. Anne and I looked at Schindler’s drawing, but I don’t know if I can show it, since it’s not been printed anywhere.