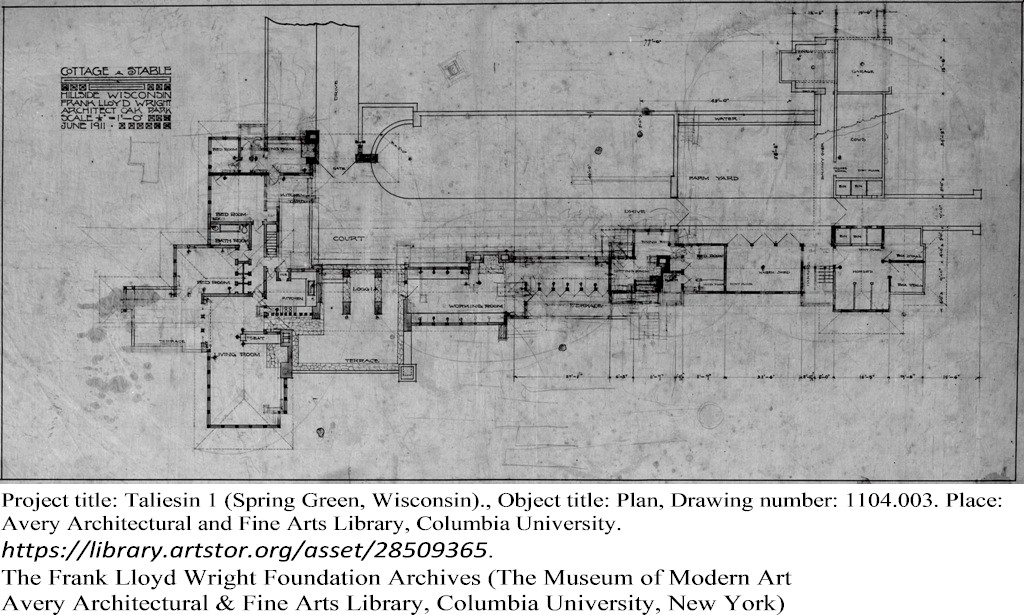

A drawing of Taliesin, executed in June 1911. This drawing is accessible from

https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/28509365;prevRouteTS=1621879846896

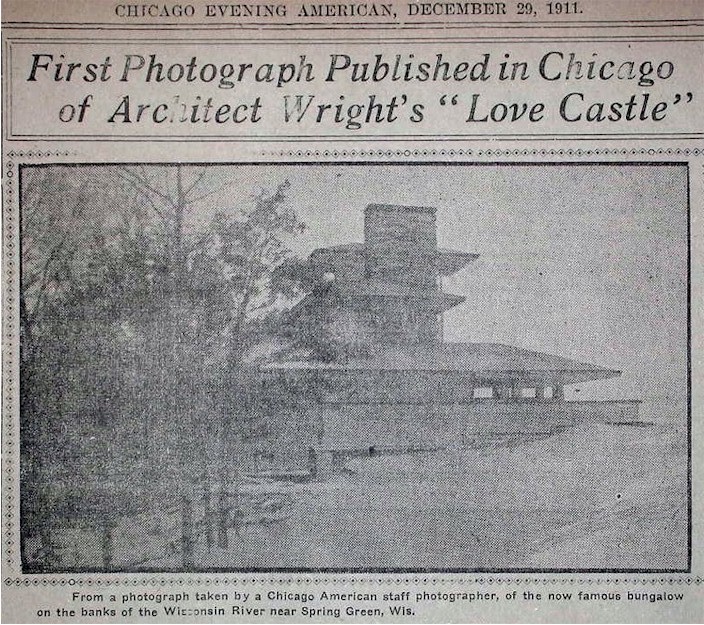

110 years ago, on May 25, 1911, the Weekly Home News (the newspaper of Spring Green, Wisconsin), noted on page 4 that:

“Mrs. Hannah Wright is building her home in Hillside valley, adjoining the old homestead, a little north and west of the old millsite. This will be a nice addition to the neat home in the valley.”

“Hannah” was her legal name, but she was known as Anna, and she was Frank Lloyd Wright’s mother.

“Hillside” was the name of the small town south across the Wisconsin river. The valley was lived in by Frank Lloyd Wright’s mother’s side of the family, the Lloyd Joneses (which is why, when Wright’s sister, Maginel, wrote about the family, she named her book, The Valley of the God-Almighty Joneses).

Why did Wright build this home?

The public perception was that Wright was building this home for his mother. He was actually building it for himself and his partner, Mamah Borthwick (she was still in Europe awaiting a divorce from Edwin Cheney, which she would do on August 5). By August1 he referred to the home as Taliesin.

Did Anna ever live there?

I have never figured out if, when, or where, Anna lived at Taliesin.

In December 2021,

I went to Taliesin West in Arizona looked at the text of some of Anna’s letters.

I wrote about looking at some of them it in my post “Anna to her son“.

She was definitely staying at Taliesin while she wrote them. Wright was in Japan working on the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. But there still no hard proof that she was there for the long-term. That she had also spent time with her other children, Jane Porter and Maginel Wright Enright.

Regardless of whether she ever lived at Taliesin, Anna did originally purchase the land where her son would start his home (or possibly she bought the land because her son persuaded client, Darwin Martin, to purchase her home so that she had the money to buy the land).

The purchase of the land:

She had purchased 31.561 acres of land on April 10, 1911 from Joseph Reider, a Lloyd-Jones neighbor.2 Frank Lloyd Wright would move to the “Hillside valley” (the Lloyd Jones valley) with Borthwick once she divorced. Thus, she’d be free to live with him.

Obviously, construction had started by late May 1911, thanks to the note in the Weekly Home News. When Wright first drew the building in April, it was labelled Cottage for Anna Lloyd Wright. It had three bedrooms (including one for a servant), a kitchen, a living room, and a “work room” across an open “loggia”.

Taliesin as constructed

By June 1911 (when someone executed the drawing above), Anna’s name no longer appeared on the drawing’s title block. However, the building was still being labelled as a cottage. Nice cottage: its living quarters had three bedrooms, two bathrooms, a kitchen and a living room. At a right angle, it had a workroom and office space. Beyond that were spaces for carriages and animals. Whether or not you’d call it a cottage, the drawing in June is fairly close to what was built.

Wright about Taliesin in his 1932 autobiography:

I wished to be part of my beloved southern Wisconsin and not put my small part of it out of countenance. Architecture, after all, I have learned, or before all, I should say, is no less a weaving a fabric than the trees….

The world had appropriate buildings before–why not more appropriate buildings now than ever before. There must be some kind of house that would belong to that hill, as trees and the ledges of rock did; as Grandfather and Mother had belonged to it, in their sense of it all.

Yes, there must be a natural house, not natural as caves and log-cabins were natural but native in spirit and making, with all that architecture had meant whenever it was alive in times past. Nothing at all that I had ever seen would do…. But there was a house that hill might marry and live happily ever after. I fully intended to find it. I even saw, for myself, what it might be like and begin to build it as the “brow” of the hill.

Frank Lloyd Wright, An Autobiography, in Frank Lloyd Wright Collected Writings: 1930-32, volume 2. Edited by Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, introduction by Kenneth Frampton (1992; Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., New York City, 1992), 224-225

About the “brow” of the hill:

Frankophiles know this, but the word “Taliesin”, in the Welsh language, translates as “Shining Brow”. Wright’s family on his mother’s side, the Lloyd Joneses, came from Wales.

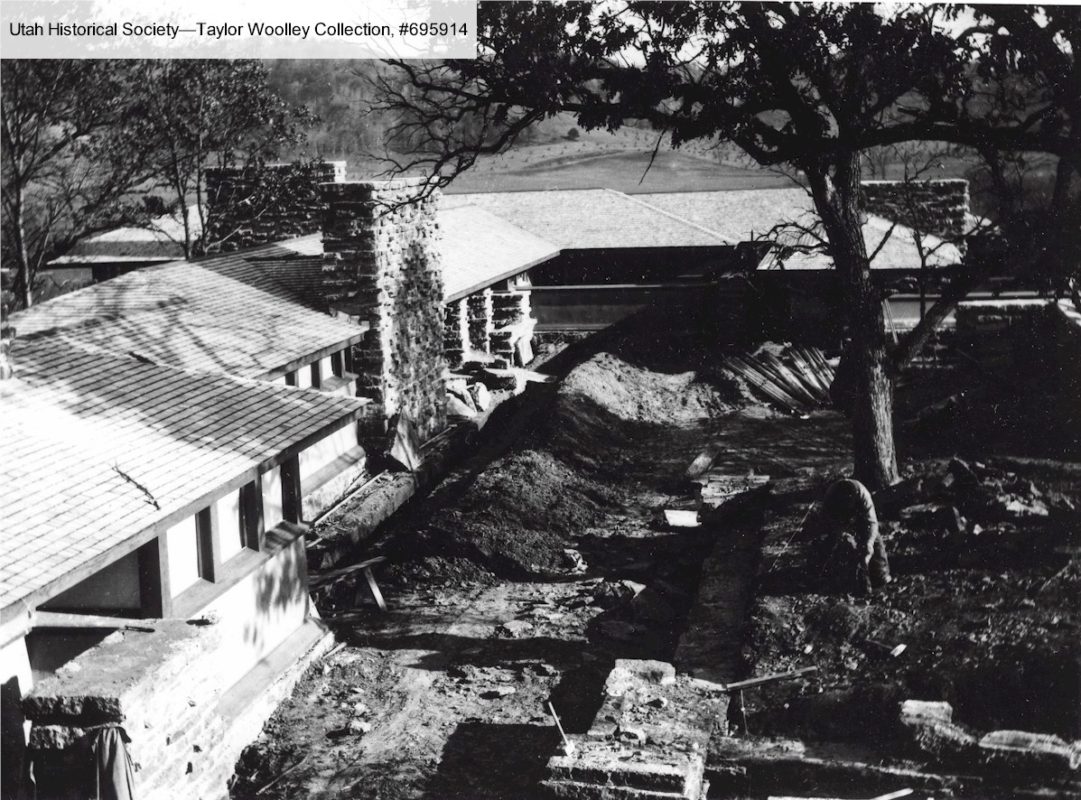

Construction photograph of Taliesin

Draftsman Taylor Woolley, who worked at Taliesin in 1911-12, took photographs all around the building. Those photos are now at the Utah Historical Society. I showed one of the photos months ago in my first blog post. Woolley printed some of these photos out. Someone put them into an album now owned by the Wisconsin Historical Society. The link to those photos is here.

So the Weekly Home News said the building was being built for “Mrs. Hannah Wright” in late May. Woolley took the photograph over three months later:

The photo above is taken from the “Hill Tower” at Taliesin, with Wright’s living quarters in the background.

Woolley’s construction photographs

The Ebay auction of an album of Woolley’s photographs (which I wrote about in The Album) were one of the most interesting things in Spring Green, Wisconsin during the winter of 2004-2005. But after that hullabaloo, writer/journalist Ron McCrea found negatives of more at the Utah Historical Society. He sent me chapters of the book he was working on, Building Taliesin: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Home of Love and Loss. If you read the book you can find out how McCrea found them, and where more photos by Woolley can be located.3

Woolley took the photograph above shortly after he came to work for Wright. Personally, I have never found photographs of Taliesin dating before that, or of construction earlier in the summer of 1911.

Also, I checked the issues of Weekly Home News newspaper published during the summer of 1911. But unfortunately, I haven’t found anything yet in the “Home News” about “Mrs. Hanna Wright” building in the “Hillside valley”.

Finally, and since I was asked this while working at Taliesin Preservation, there is no photograph of Frank Lloyd Wright “breaking ground” for his home.

Wright didn’t want people to know what he was up to in Wisconsin—so there’s no photo of Wright smiling happily while holding a gold shovel.

Regardless, that small note in the Weekly Home News touched on something that altered Spring Green, and southwestern Wisconsin, permanently.

Originally published, May 24, 2021.

The drawing above is drawing #1104.003, from The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art |Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York).

Notes

1 On August 26, 1911, architect John Moore sent Wright a telegram, wanting to visit his home. Wright scrawled at the bottom of the telegram (in preparation for the reply), that Moore and his friends “Will be welcome to Taliesin.” As I was transcribing it, I thought that this might have been the first time that Wright referred in writing to his house by that name.

The telegram is identification #K017E01, The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (Museum of Modern Art|Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York).

2 People often think that the Lloyd Jones family owned the land where Wright built Taliesin. I think that’s what Wright wanted people to believe. The land title shows that it had not been owned at any time by a Lloyd Jones family member before Wright bought it. Until 1911, neighbor Joseph Reider owned it. There’s no bad reason why Wright didn’t tell people the truth; maybe he felt it made a better story.

3 I wrote the captions for many of Woolley’s photos in McCrea’s book, in part because I knew the photographs well (and, as I noted in another blog post: this stuff is fun for me). Unfortunately I lost most of the the emails between McCrea and myself due to something that happened with email at work (most were fubarred←if you don’t know the definition of “fubar”, look it up). Doesn’t matter so much, but it bums me out a bit.

You walk up the steps at Taliesin to Wright’s studio at Taliesin (the north wall of the studio is to the right). The parapet from the Taliesin I photo ended at the stone that is to the left of the tree trunk (the tree trunk is to the left of the window that’s on the extreme right in the photograph) .

You walk up the steps at Taliesin to Wright’s studio at Taliesin (the north wall of the studio is to the right). The parapet from the Taliesin I photo ended at the stone that is to the left of the tree trunk (the tree trunk is to the left of the window that’s on the extreme right in the photograph) .