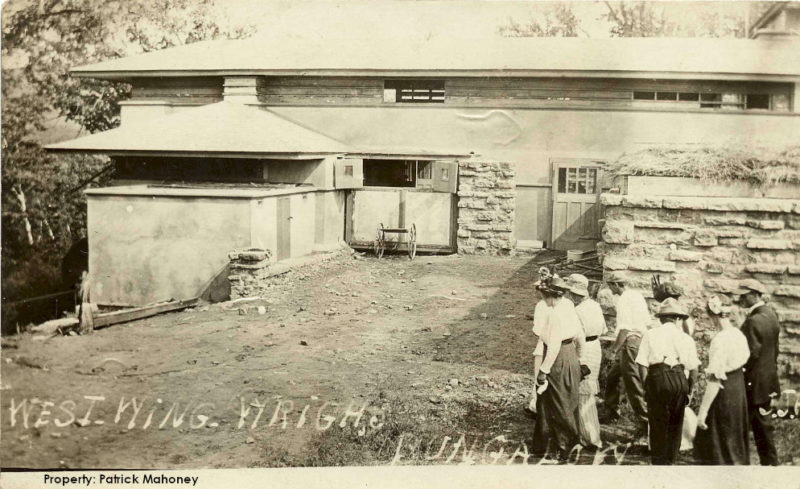

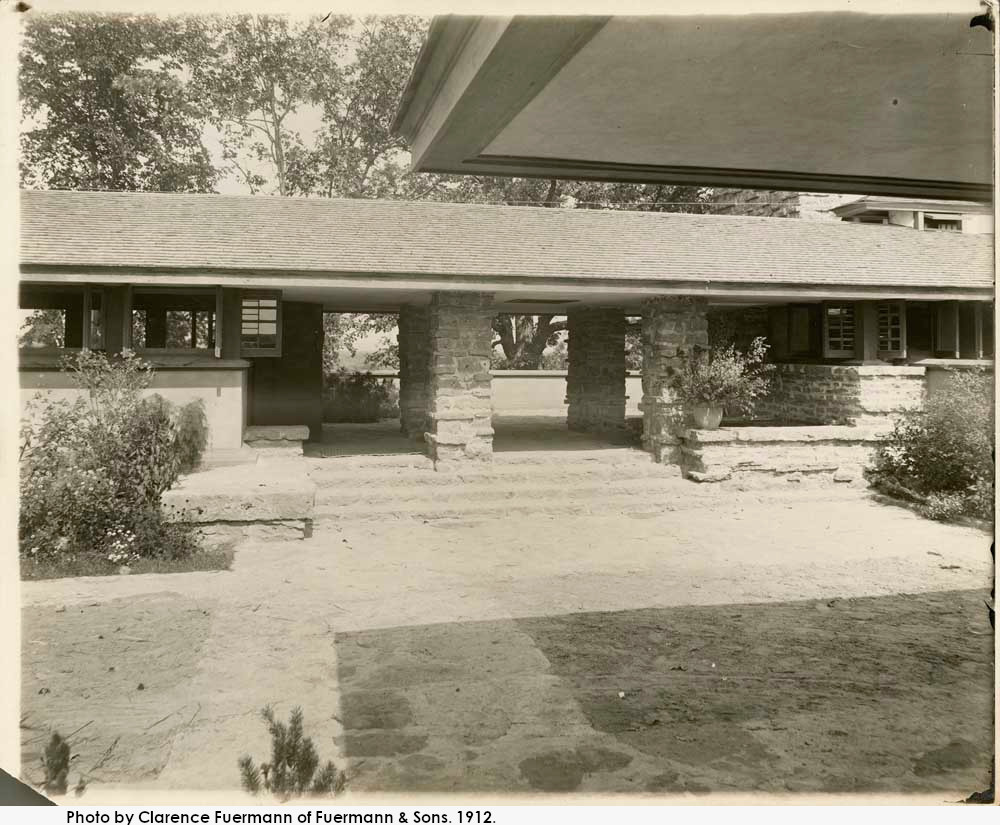

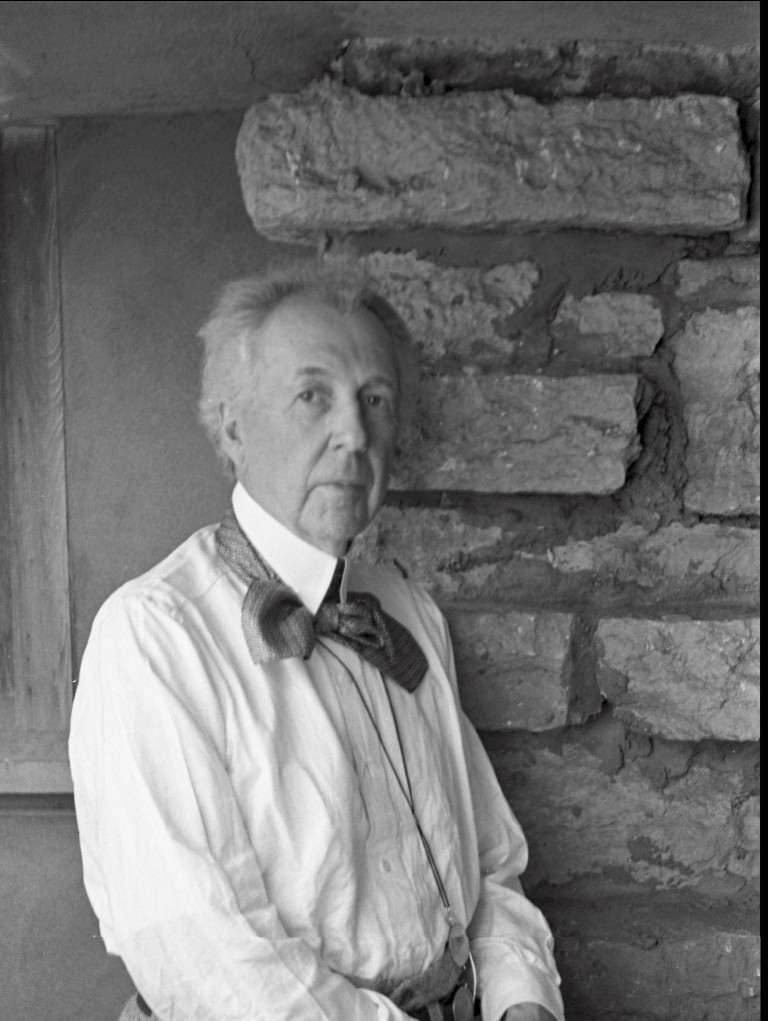

A postcard looking (plan) northeast at the western façade of Taliesin’s hayloft, summer (the hayloft is under the roof). Because the collection of people are unexpected at a farmhouse, Randolph C. Henning (who collected this postcard), thinks this was taken the day after Taliesin’s 1914 fire and murders.

I wrote The Oldest Thing at Taliesin (stuff that goes back to 1911-12), and was going to leave it at that. But before I posted, I realized there were too many things to point out. I needed to divide it into two posts. So, that was part I.

Here’s part II.

Like last time, I’m going back to stone because it’s the easiest material to trace at Taliesin. That’s because Taliesin’s shingles, wood, and plaster has to be replaced. And I’m not sure how much of the window glass at Taliesin goes back to 1911-12.1

Therefore, in 2010,

Taliesin Preservation‘s Executive Director taped a printout of the picture at the top of this post onto my computer monitor.

In 2005, she (Carol) also told me about “The Album” on auction at the online site, Ebay.

Architect and writer, Randolph C. Henning, had sent her the scan of the image. Although he knew what you see in this image (the courtyard on the other side of Taliesin’s Hayloft), he wrote asking for help on any research on the rest of the images in his upcoming book, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin: Illustrated by Vintage Postcards (this image is on p. 39).

I’d never seen anything like that image because

you can’t really see this view today.

Why?

Because that nutter changed his house all the time, of course.

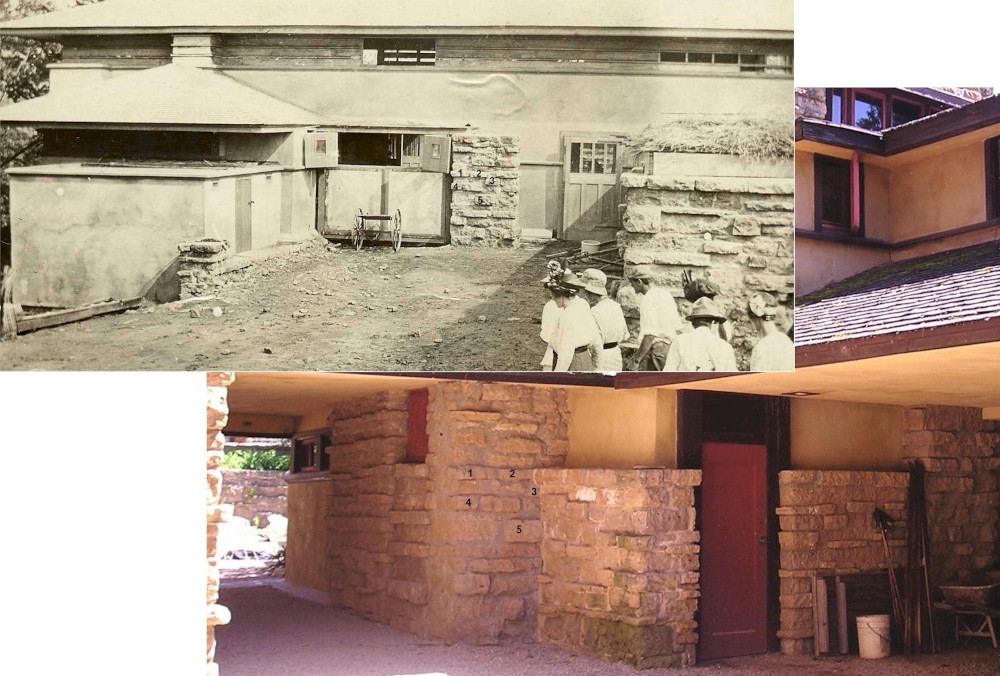

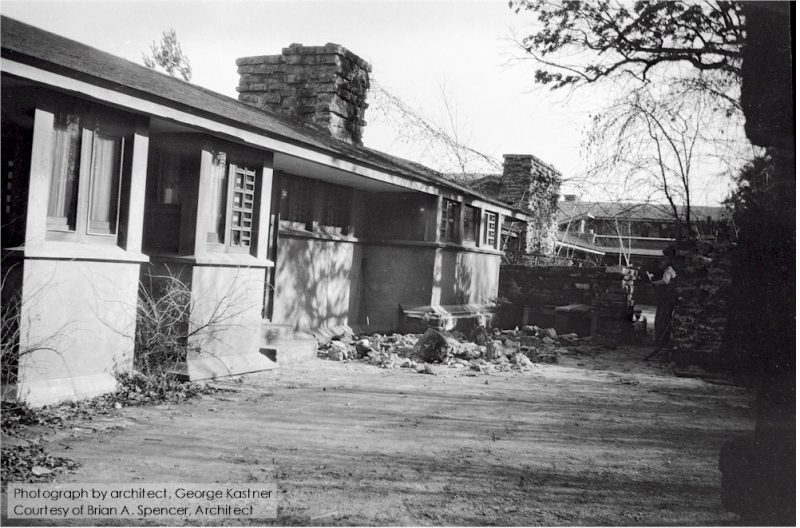

A similar angle of view is in the photo below:

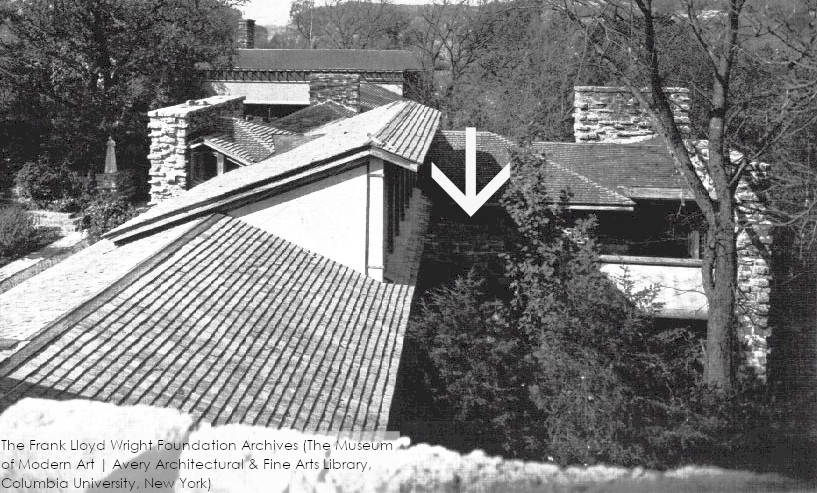

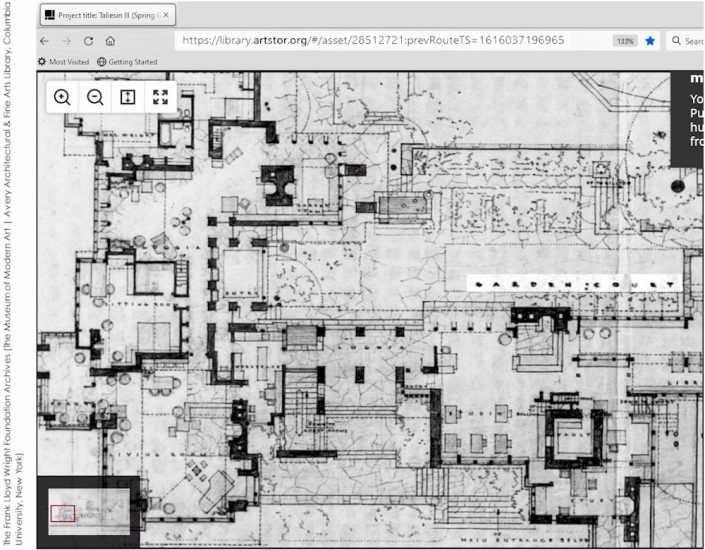

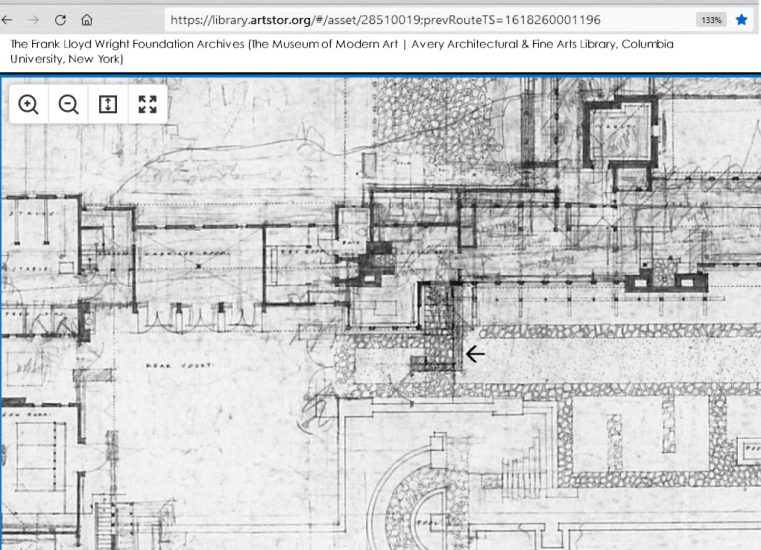

I took this photograph from the roof of Taliesin’s former icehouse. The photograph is looking northeast according to Taliesin’s plan direction. Taliesin’s “Work Court” is one floor below.

I was up on this part of the roof with a member of the Preservation Crew. He was showing me details on the re-roofing. And, NO, you cannot stand on this roof while you’re on a tour.2

Almost nothing in this photograph matches what you see in the c. 1914 postcard at the top of this post.

But,

even though everything’s different here’s what got my attention: the stone pier under the hayloft.

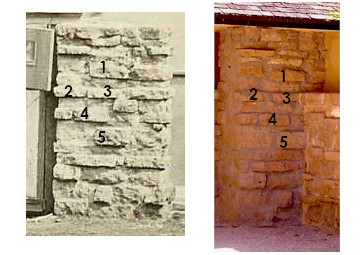

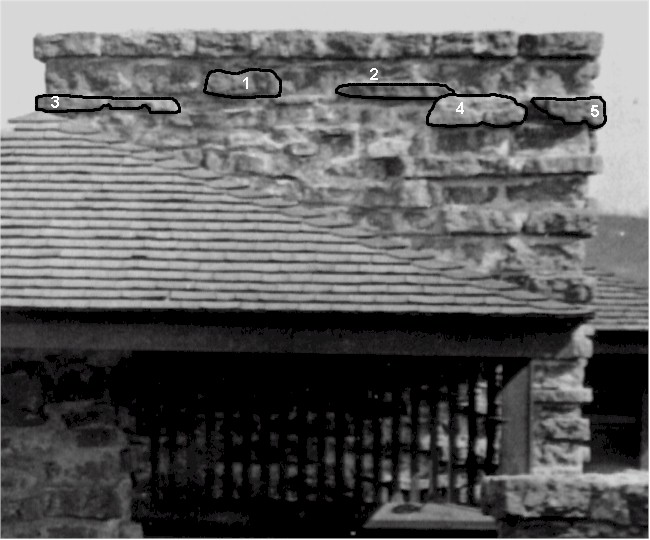

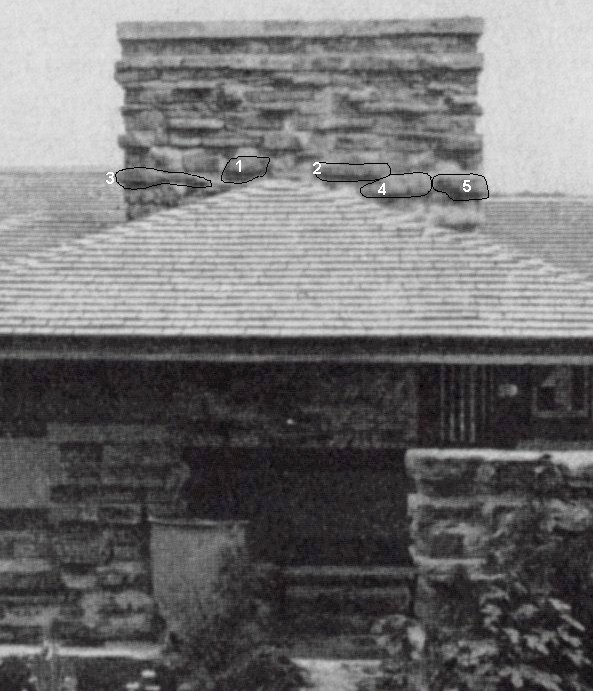

THAT is still there! Here’s a comparison of the 1914 photo and the photo from 2004:

In the Work Court, looking southeast according to Taliesin’s plan direction. This photograph has the stone pier that I saw in the 1914 postcard. The image below has both the old and new photos, with the stones in the pier compared.

Here’s the stone pier in a close-up of the two photographs:

TA-DA!

More Taliesin 1911-12:

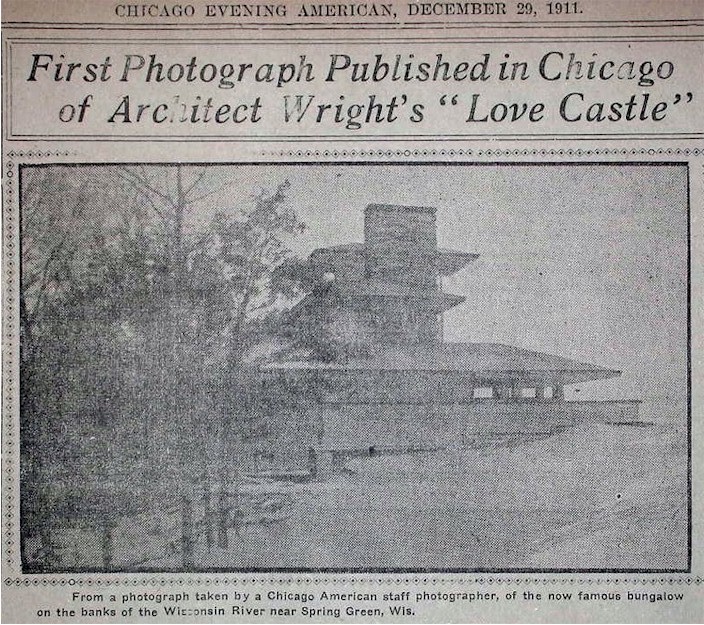

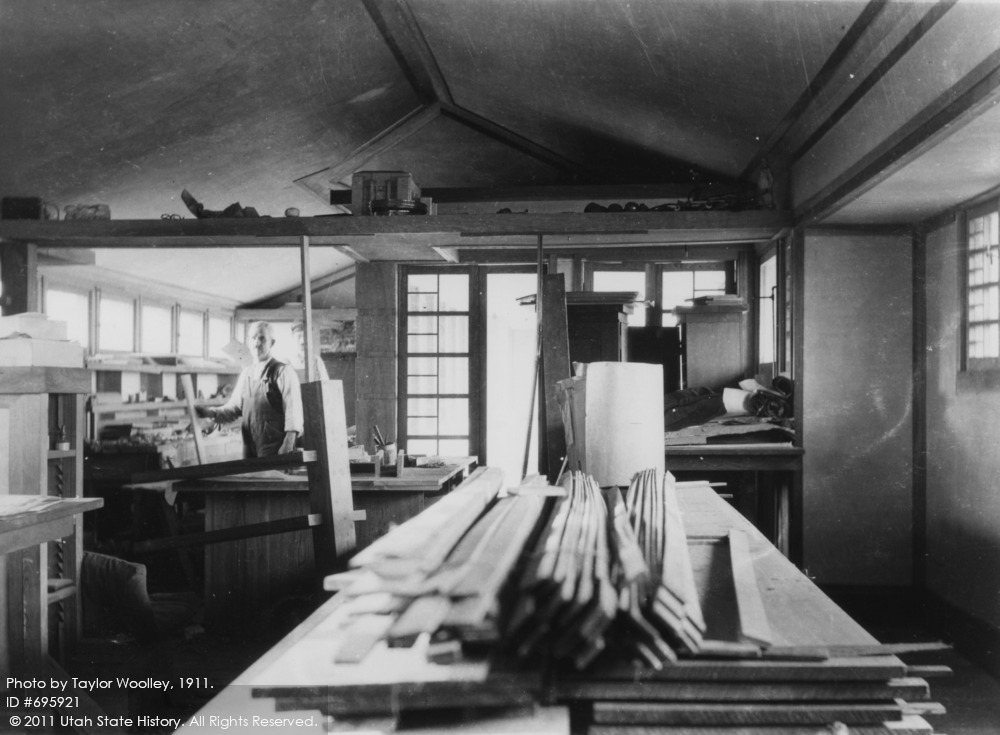

The next photo appeared in 1911. I first saw it two years ago when the Chicago Tribune treated us all to was in a published article:

This photograph was taken December 25, 1911. The photographer was looking east/southeast (according to Taliesin’s plan direction) at Taliesin’s agricultural wing in 1911. The photo was taken on that day when Wright gave the disastrous press conference at Taliesin.

This, and the article that included it,

made me so happy that I wrote a post about it: “This is FUN for me…“.

Props go to Stan Ecklund on Facebook who, in 2020, first alerted me (and other Frankophiles) to this article. Stan created and curates two Wright-based groups on Facebook, The Wright Attitude, and Wright Nation. The “WA” is a private group, but Wright Nation on Facebook is public, here. If you are in the WA group, Stan posted the link to the article in the Tribune on Dec. 4, 2020.

Again, you can’t see the same view today because of Wright’s changes at Taliesin.

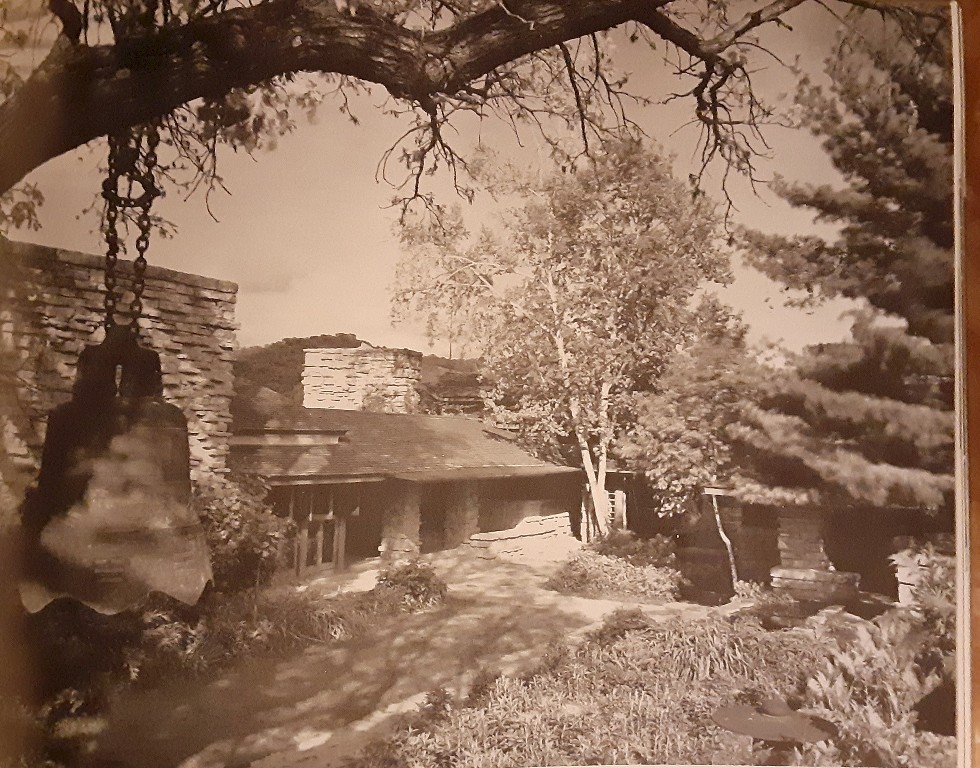

But I found a photo on Wikimedia Commons that’s shot from a similar angle. That’s below:

Looking (plan) southeast to the chimney that’s in the photograph from 1911 in the Tribune.

Taken by Stilhefler while on a tour. Click the photo to see it on-line.

I am not publishing the second photo from the Chicago Tribune. Most of what you see in the second photo cannot be seen on a tour and if you read “This is FUN for me…”, I explain it some more.

Then there’s the Hill Crown:

And its retaining wall:

I took this photograph in April, 2005.

Most likely, there are other parts of the retaining wall that go back to 1911. However, I do not think you’ll be able to look at those places for any length while on a tour at Taliesin.

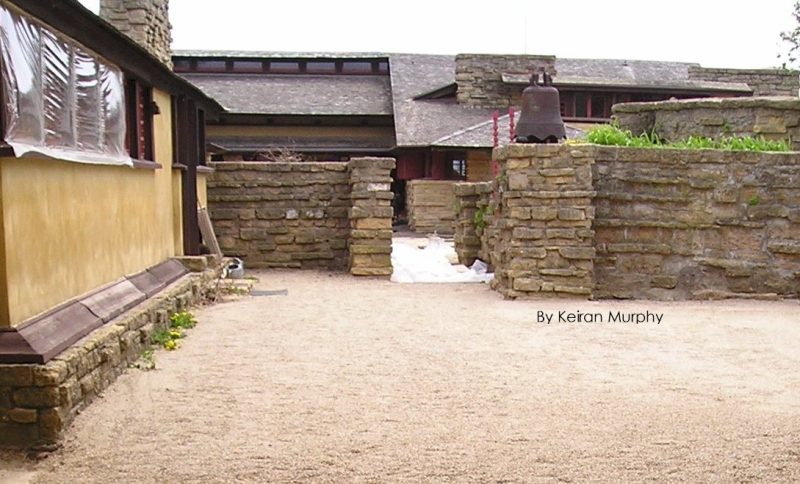

Lastly, I’ll show something else you can see on tours:

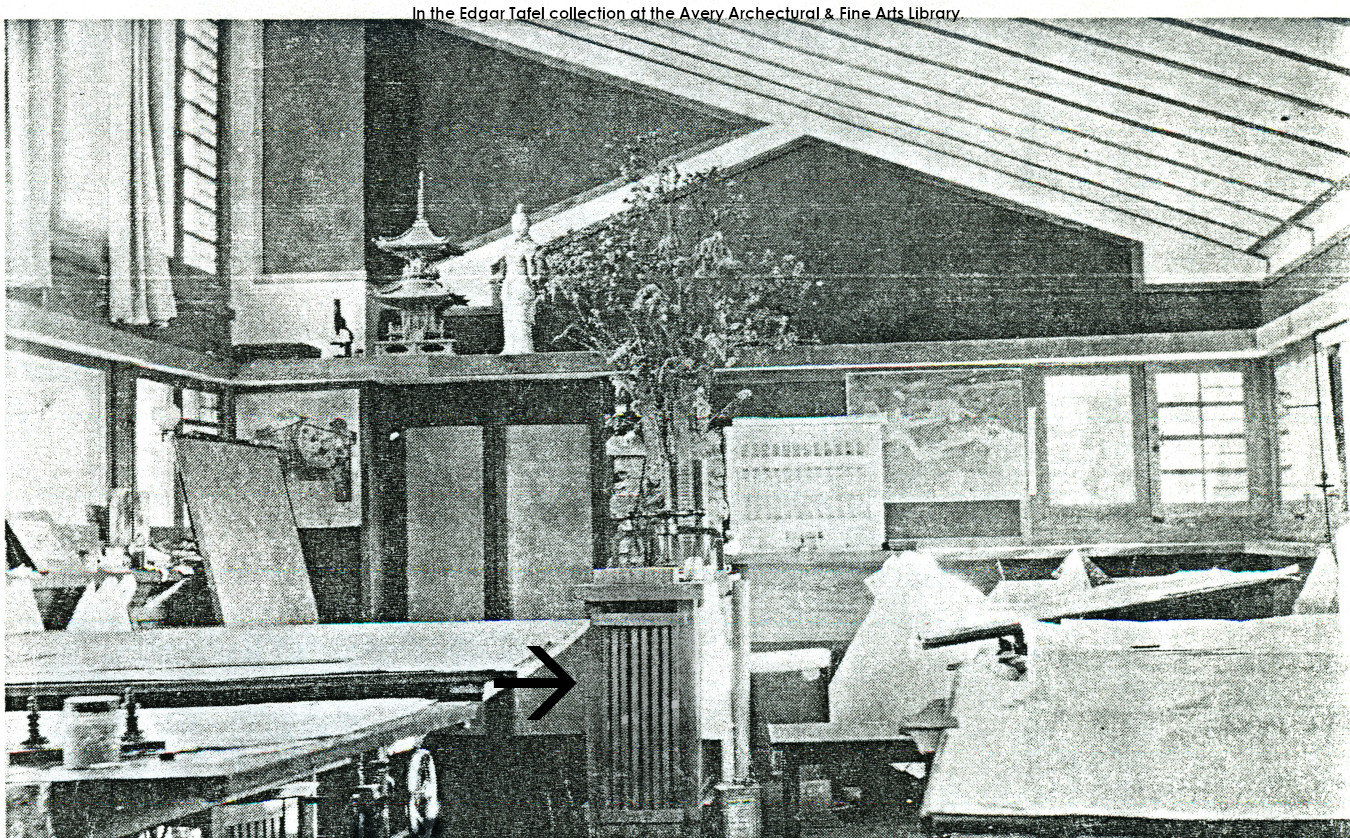

This was also published in Architectural Record magazine in 1913. Here’s where I wrote about it.

Look at the pier on the right, with the pool. The open windows on the right are at the kitchen (today it’s called the Little Kitchen). Every tour you take at Taliesin walks near that pool.

I put a present-day photo of it, below. The person who took this photo in 2018 also took the one above.

Taken in the Breezeway at Taliesin. Looking (plan) southeast at the stone veneer on the west wall of the Little Kitchen.

Photo from July 4, 1918, by Stilhelfer. Click the photo above to see it on-line. You’ll see that this photo has been cropped.

I love this area.

Wright changed things so much at Taliesin that I’m intrigued when he didn’t.

That’s all I’ve got the time to show you right now. Oh, and last thing: remember that these parts of the building I talked about were just what you can see.

So, thanks again for coming along!

Published November 26, 2022

Randolph C. Henning acquired this and sent this to the Executive Director of Taliesin Preservation while he was working on Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin: Illustrated By Vintage Postcards. You can see the photo on page 39. Henning sold his collection to Patrick Mahoney, AIA.

Here’s “What is the oldest part of Taliesin? Part I“

Notes

1 I could go and point out windows that seem like they were at Taliesin in 1911-12, but I dunno.

2 “WHAT – do you think we’d just walk onto the roof?”

No, I do not think you would.

However: one time a person arrived at the Frank Lloyd Wright Visitor Center in January or February and wanted to know if they could go into the buildings on the Taliesin estate. I asked, “Did you see the notice on our website that there are no tours at Taliesin until May 1?” The person replied nicely that, “Yes, we saw that. But you didn’t say the estate was closed.” So I’m double checking.

You walk up the steps at Taliesin to Wright’s studio at Taliesin (the north wall of the studio is to the right). The parapet from the Taliesin I photo ended at the stone that is to the left of the tree trunk (the tree trunk is to the left of the window that’s on the extreme right in the photograph) .

You walk up the steps at Taliesin to Wright’s studio at Taliesin (the north wall of the studio is to the right). The parapet from the Taliesin I photo ended at the stone that is to the left of the tree trunk (the tree trunk is to the left of the window that’s on the extreme right in the photograph) .