No, not the first time he violated it.

I wrote about that before when introducing you to the second Mrs. Wright.

In this post I’ll write about the second (and last) time.

As I wrote once before, information about the Mann Act is something you learn when working at Taliesin.

In particular, the Mann Act is related to what happened to Frank Lloyd Wright on October 21, 1926, at the cottage in the photo at the top of this post.

It started,

as things do with Wright,

in a story that got really complicated.

Let’s go back

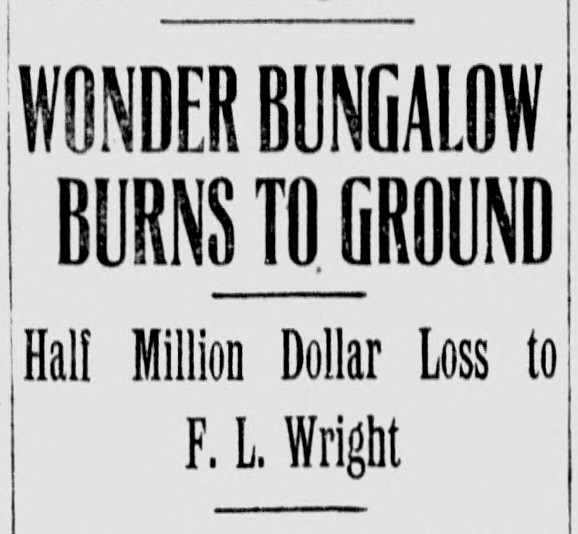

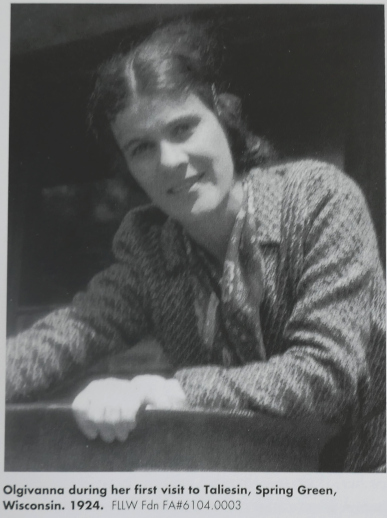

to Wright’s second wife, Miriam Noel. She left him by early May 1924, then almost 6 months later, he met his future wife, Olgivanna. Their new relationship was practically tried by fire—Taliesin’s second fire 5 months after they met. Olgivanna had their daughter, Iovanna, in December while she was chased out of the hospital after giving birth. And, in the next year, Wright was having financial problems while struggling to find clients. What’s more, Miriam was still refusing to settle their divorce.

This was quite a problem for everyone.

Especially, where Wright lived.

Spring Green was dealing with the “Chicago boys”: those reporters from that city’s newspapers. They were around, writing about Wright’s problems with Miriam. She had shown up at Taliesin in early June 1926 trying to get in while the Chicago Boys took photos.

Taliesin was legally her home, after all.

So William Purdy, editor of Spring Green’s newspaper, The Weekly Home News, wrote about this sorry business in the June 10th edition.

Also, Purdy allowed Wright to publish an apology to the people of the village. Here it is in part:

Architect Makes Statement to Public

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT THANKS HOME PEOPLE.

To the Countryside:

Taliesin seems to be a storm center for conflicting human interests and emotions. Three times I have built it up from its ashes;1 each time stronger and more beautiful than before tragedy destroyed it. The cooperation of the countryside was mine in all this and I have appreciated it more than I can tell. But I have never thanked my neighbors and townspeople directly for their friendship and forbearance. I want to do so now, particularly in consideration of their “hands off” attitude in this last attack—this attempt, made in hatred and a spirit of revenge, to destroy any usefulness I have and make what I have struggled to establish here useless to me or anyone….

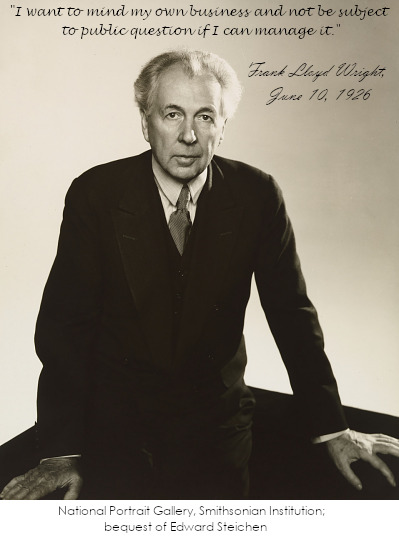

Then, the last paragraph includes my favorite part:

Enough of that. What I want to say to you was that I like you people…. You all seem home-like to me. I’ve been about all over the globe and come back here with that feeling of coming “home” we all seek somewhere, and too often seek in vain…. I want to stay here with you, working until I die. I want to mind my own business and not be subject to public question if I can manage it. At the present times it looks as though I yet had some distance to go—and I might die before I got there. I must be patient and I hope those of you who don’t believe in me very much, perhaps, will be patient too—along with those who are closer to me and know better what I have had to contend with and what I would do if I could. I think the countryside deserves the best of me and if you who make it what it is give me the benefit of the doubt in all this for a year or two, I believe I will come through right side up and you may yet take pride in Taliesin as I have always hoped and believed you would do.

With affection, such as I am

Your—FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT.

If you didn’t see it above, check out the photo I put together below:

Honestly, I wanted to show this because it looks like a motivational poster that’s taken a bad turn.

Despite what he wrote to his neighbors in 1926, things for Wright would not get better in “a year or two.”

In fact,

they were going to get worse that fall.

At the end of August, one of Wright’s attorneys (Levi Bancroft) advised Wright to spend a while away from Taliesin. Bancroft and others were trying to settle things with Miriam and the Bank of Wisconsin.

So, Wright and his coterie —Olgivanna, her daughter, Svetlana, and Iovanna—eventually went to the cottage you see at the top of this post. It was on Lake Minnetonka in Minnesota, where they all lived for about a month.

But unfortunately,

as biographer Meryle Secrest wrote,

Wright could not have known that by driving Olgivanna across the Wisconsin-Minnesota state line, instead of having her get out and walk (presumably to demonstrate she was not a “victim”) he had given the bureau new evidence under the White Slave Traffic Act [a.k.a., the Mann Act].

Meryle Secrest. Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography (Alfred A. Knopf, New York City, 1992), 327-328.

And, on October 21, 1926

there were at the cottage when they were apprehended and brought to the county jail for the night. They released everyone but Wright the next day. Then, he stayed for the weekend until they could all see the judge.

Although Svetlana’s father, Vladimir Hinzenberg, dropped the charges once he saw that she was no longer in trouble, the event caused a permanent rift between Hinzenberg and her. In fact, her son Brandoch Peters2 later told the LaCrosse Tribune that this was why she always signed her name, “Svetlana Wright Peters”.3

A good thing about this is that the tide began to turn against the second Mrs. Wright. Around that time her lawyer, Arthur Cloud, said, “I wanted to be a lawyer… and Mrs. Wright [i.e., Miriam] wanted me to be an avenging angel.”4

One last thing about the cottage in Minnesota:

Its photo shows it with a hipped roof and apparently windows all the way in the back. When I first saw that photo over a year ago, I instantly remembered Graycliff, a home in Derby, New York. Wright designed it that year, 1926, for Isabelle Martin, wife of longtime client, Darwin Martin.

My photo of Graycliff is below:

I don’t know if there’s any connection, but I was really struck by the resemblance to this home against a lake.

Posted October 17, 2024.

The photo at the top of this post is here from the Digital Collections of the Hennepin County Public Library.

Notes

- He says “three times I have built it from its ashes”, but Taliesin was only destroyed twice by fire: in 1925, but also 1914. I think Wright might have meant that the first construction was atop his former home/life in Oak Park.

- Brandoch is seen talking about his grandfather in this video, Brandoch Peters Remembers, Part 1. Part 2 is here.

- Susan Smith for Lee Newspapers. “Grandson of Wright offers his memories”, La Crosse Tribune, December 14, 2003.

- Meryle Secrest. Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography, 331.