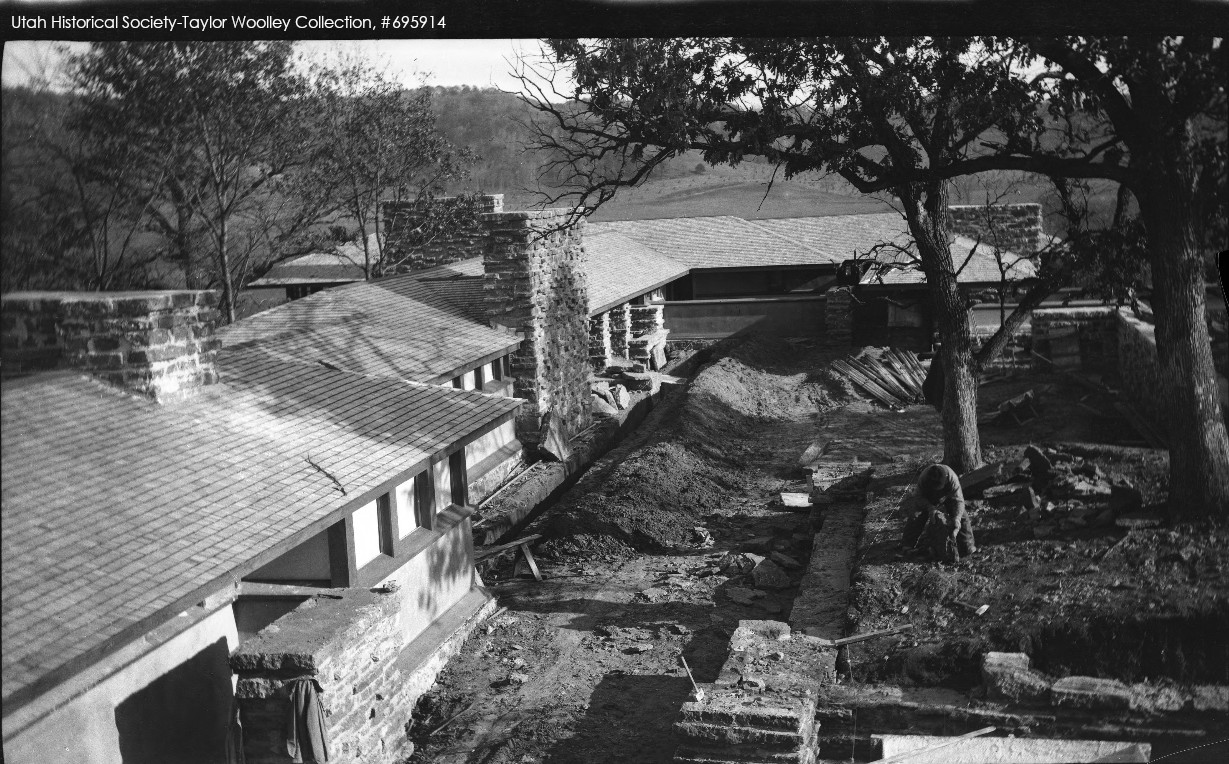

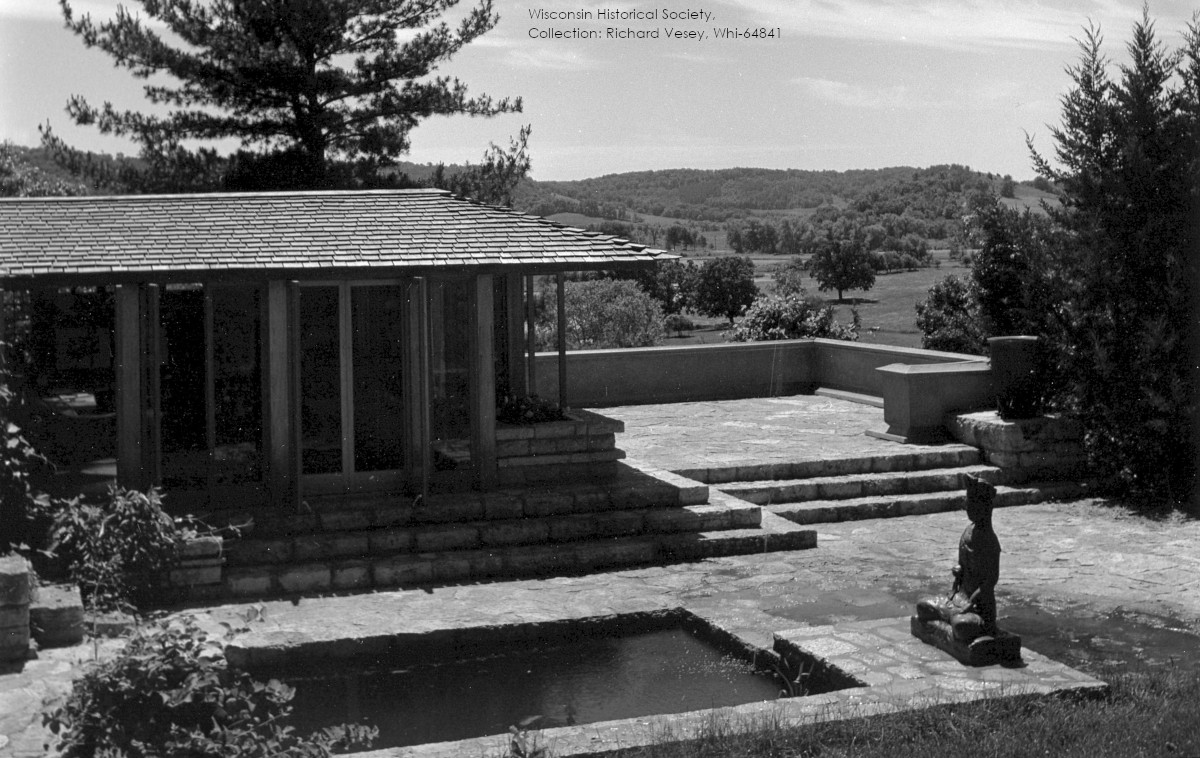

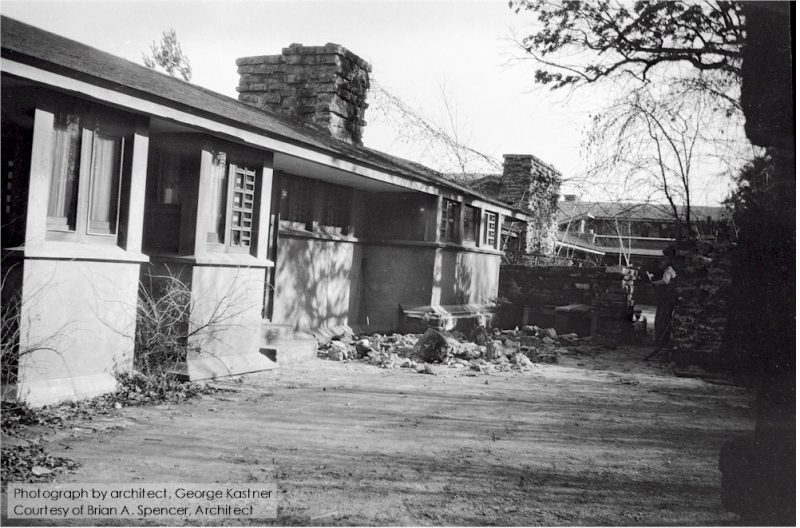

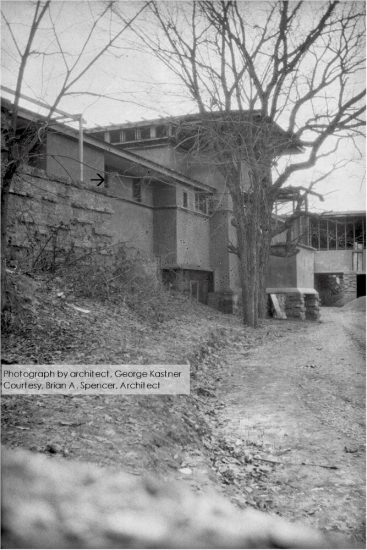

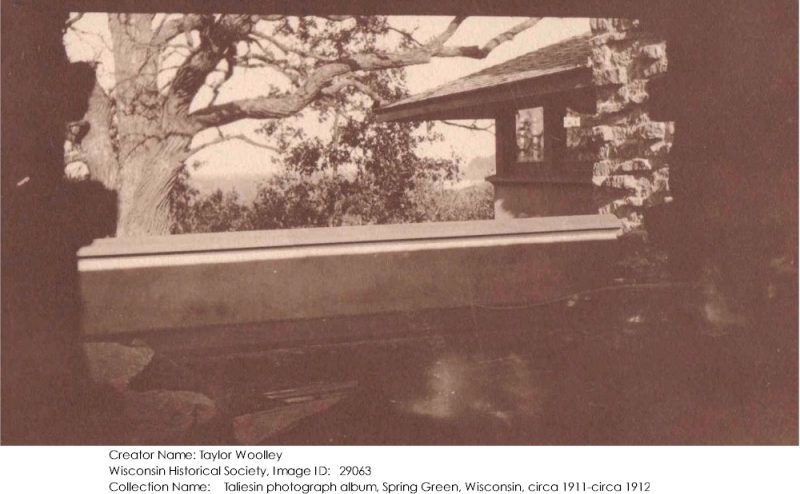

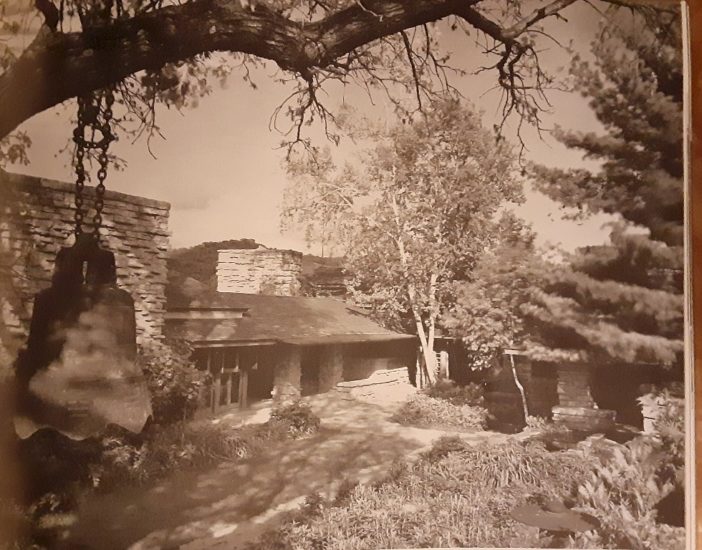

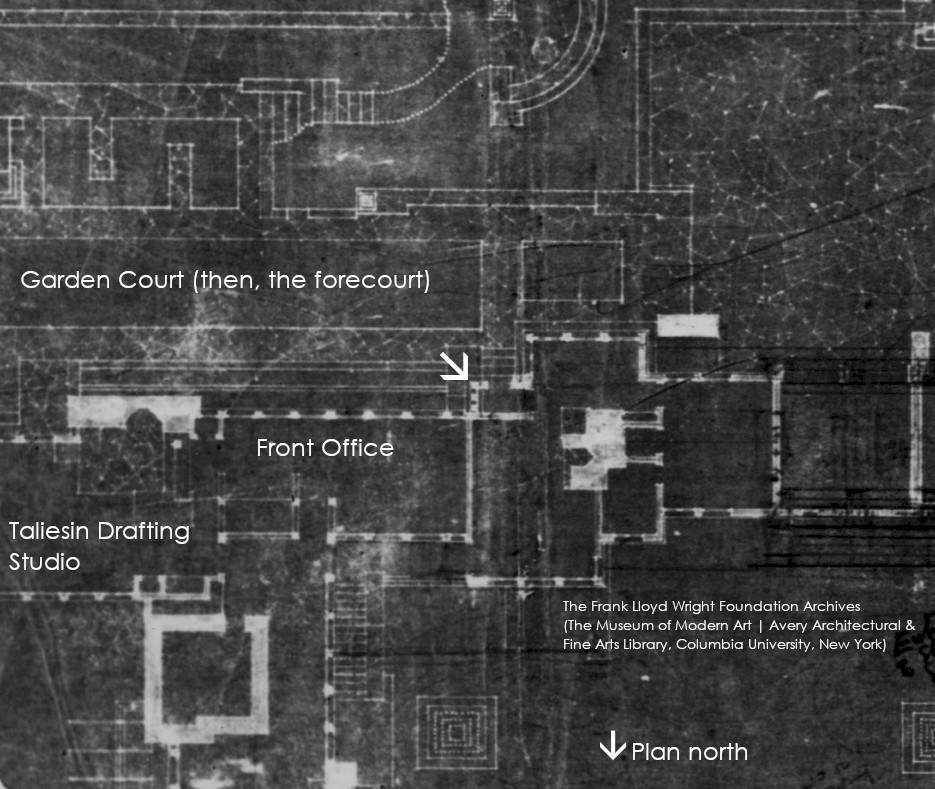

In 1929, architect George Kastner (then, a draftsman for Frank Lloyd Wright) took the photograph at the top of this post. It looks west in Taliesin’s Garden Court while stonemasons lay the wall that separates this courtyard from the other courtyards at Taliesin. This wall insured that this courtyard would be free from cars.

Today I will write some other things that I’ve not been able to figure out at Taliesin.

It’s part of the enjoyment all over Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin estate (and all of its buildings): there’s just so much to know!

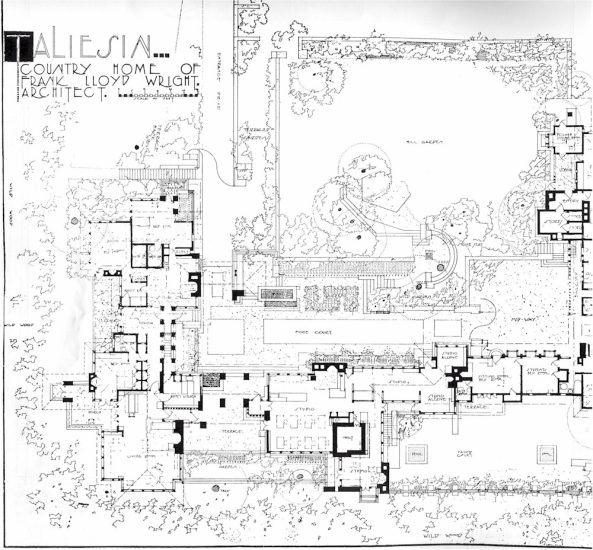

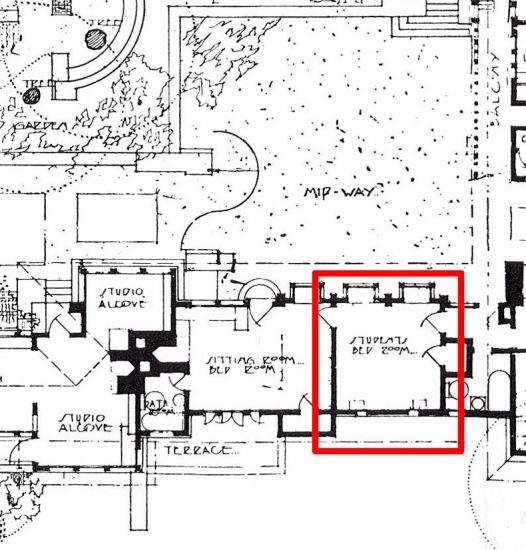

I will just concentrate on the Taliesin structure (not the entire estate).

First of all:

while I thought you Frankophiles out there would like the photo at the top of this post

I am going to talk about what’s behind the wall you see under construction in the photograph at the top if this page. The photo is great, but there are things behind it that I haven’t figured out.

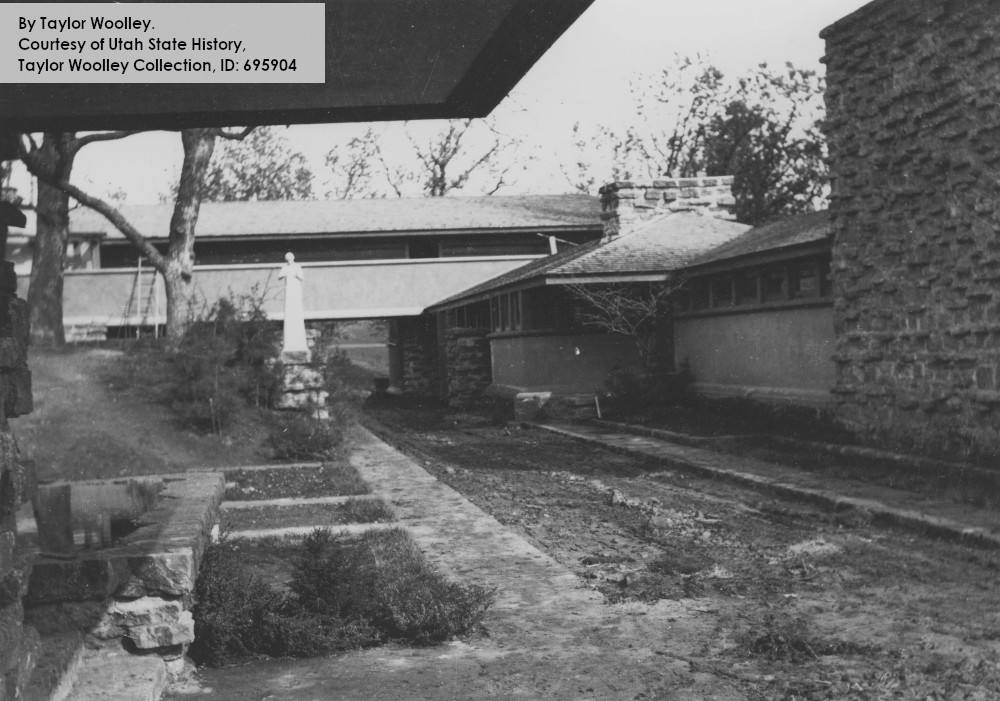

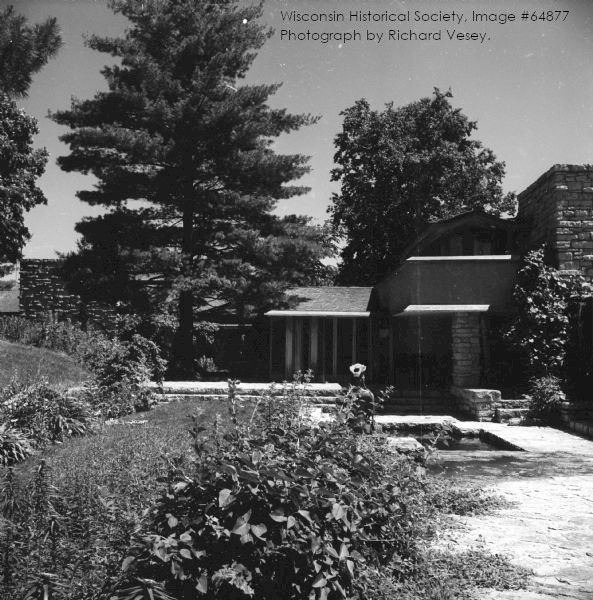

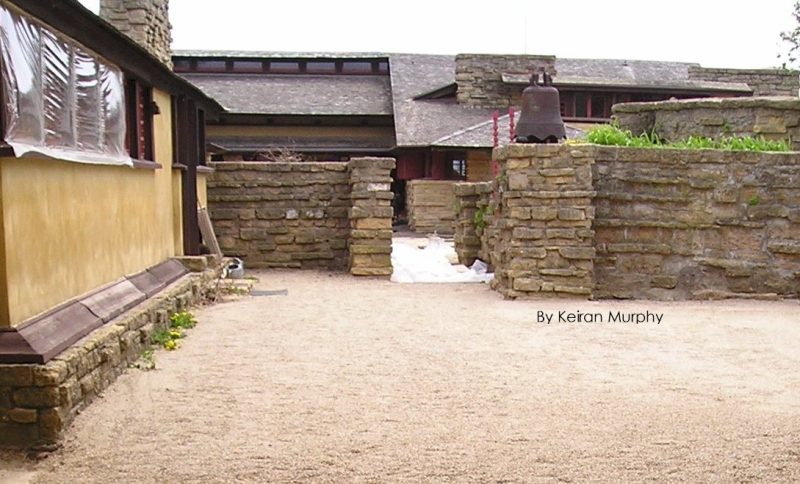

I’ll show two photos taken behind that wall that show what I can’t explain:

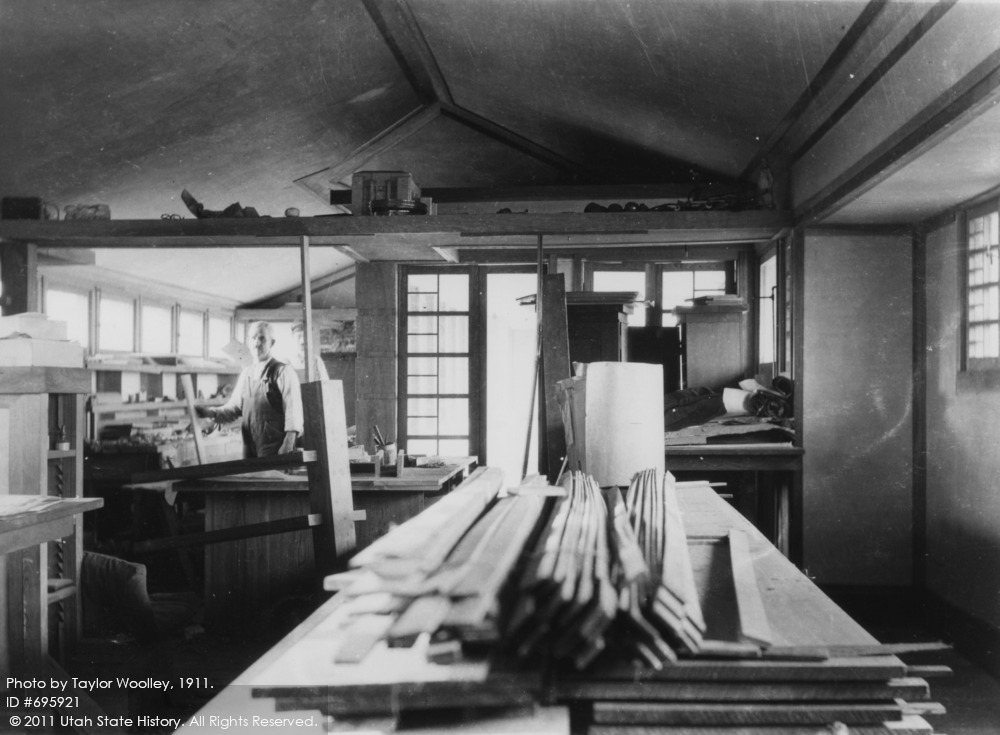

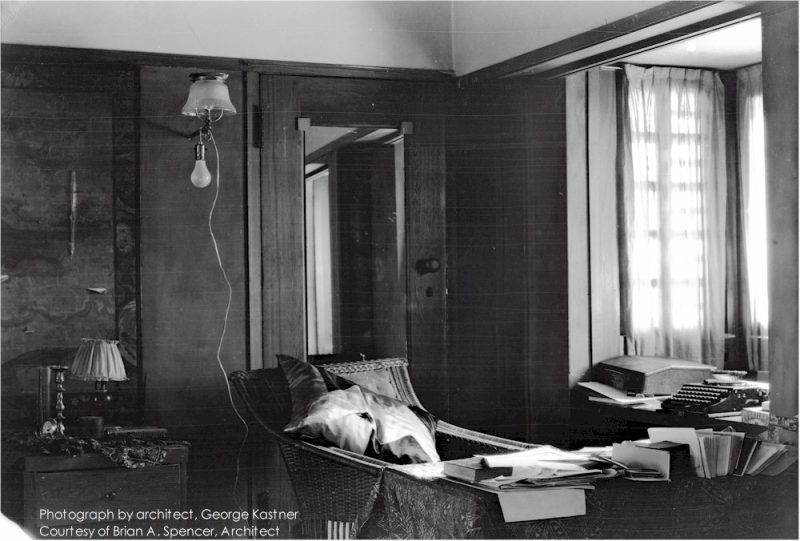

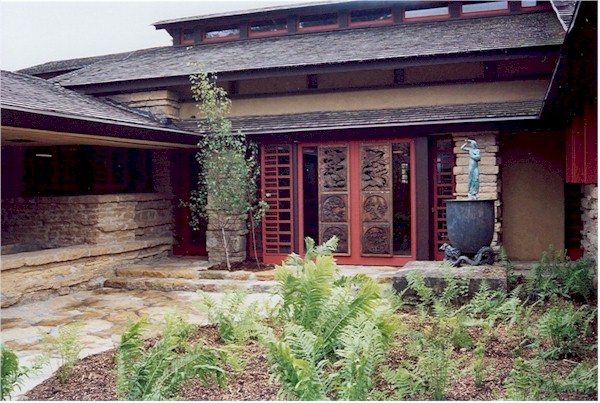

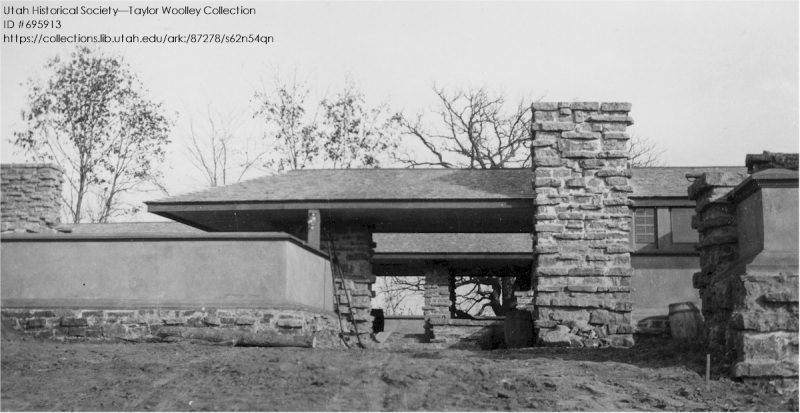

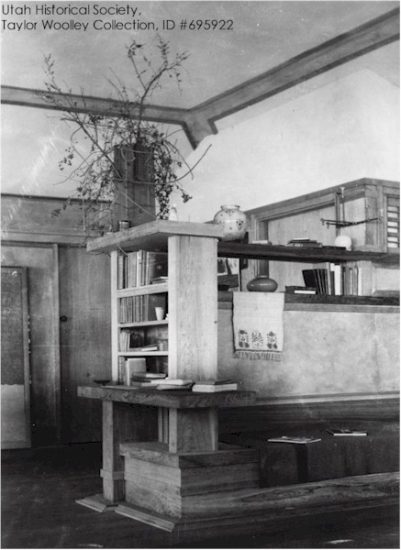

You’re looking at the door into Taliesin’s Front Office. Its windows look onto Taliesin’s Entry Court.1

I put the arrows in the two photographs to show you the part that I’m curious about. The arrows point at pieces of wood embedded in the two piers. So it looks like something was there that was maybe horizontal. Was it a wooden gate?

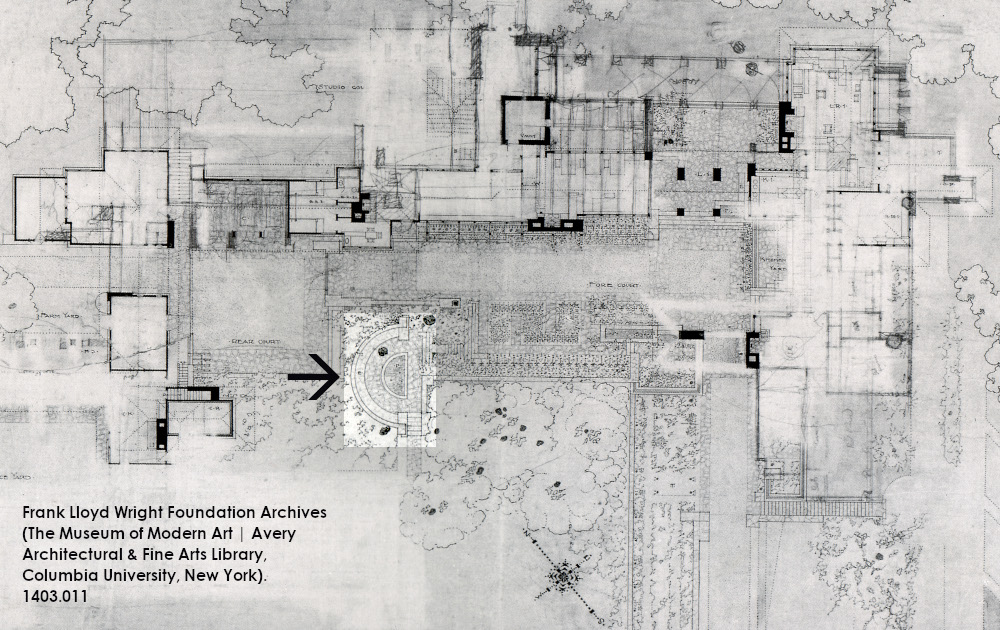

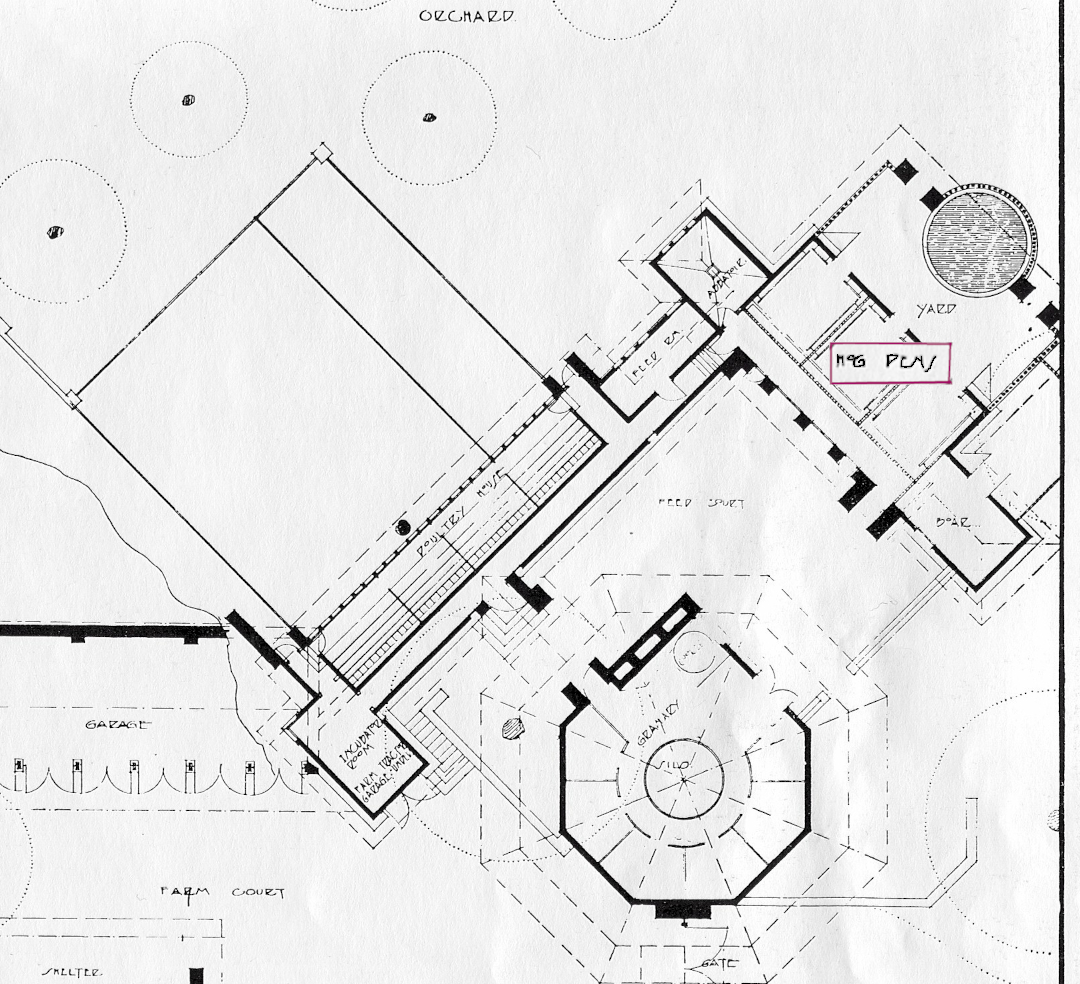

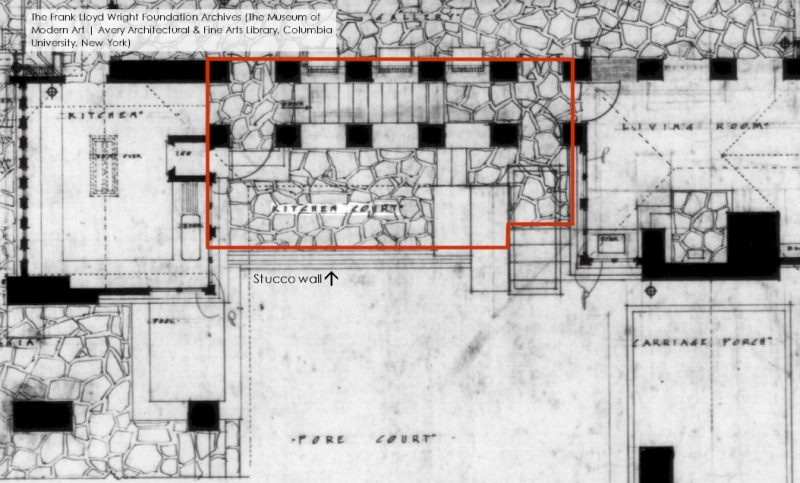

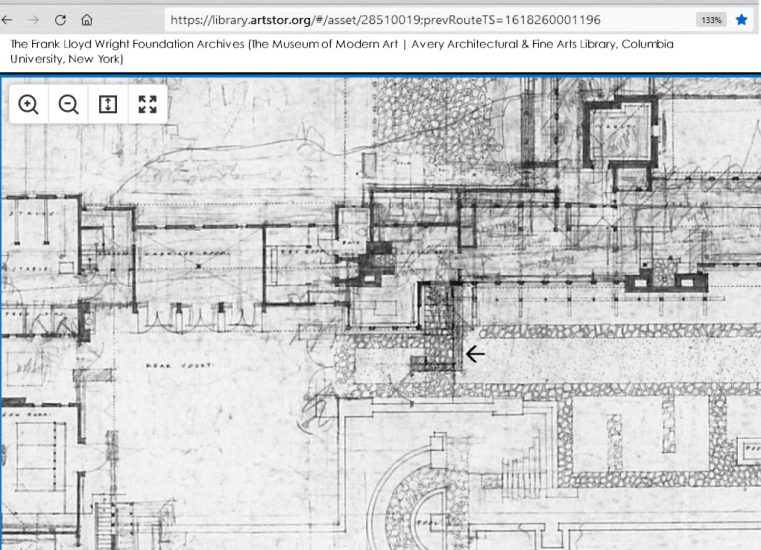

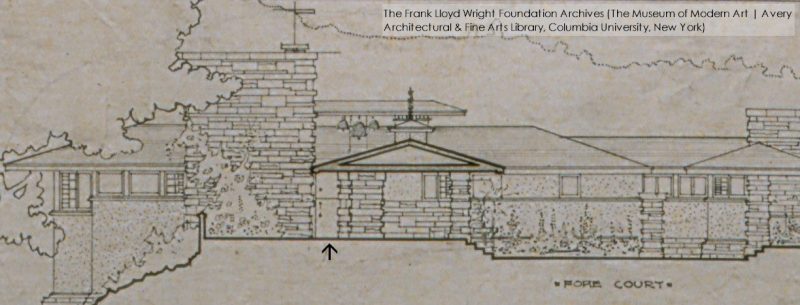

The pieces of wood are gently worn and don’t look like they’ve been hacked off. But they’ve been there for a long time. And I cannot figure out when they were put there, or what their original purpose was. The piers might have something to do with the drawing from the Taliesin II era (1914-1925), below, but I do not know:

But they do not appear in drawings, and photographs give me no clue of their purpose or use.

Another Taliesin change:

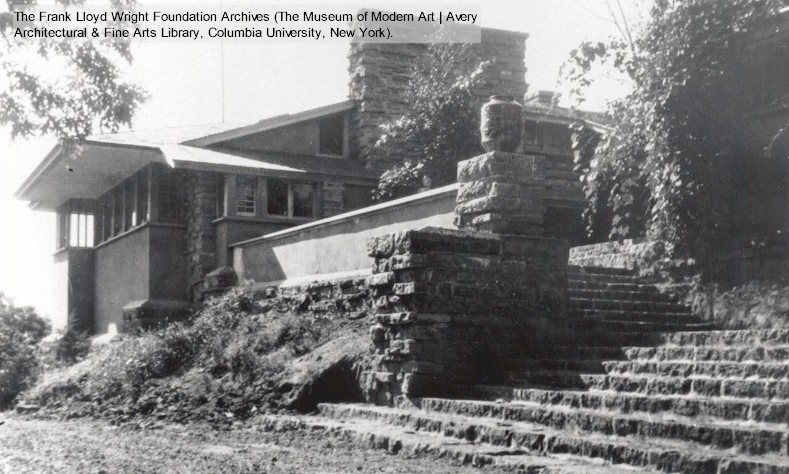

There was something that Wright changed to the west of this area. It’s on the south side of the old cow barn.

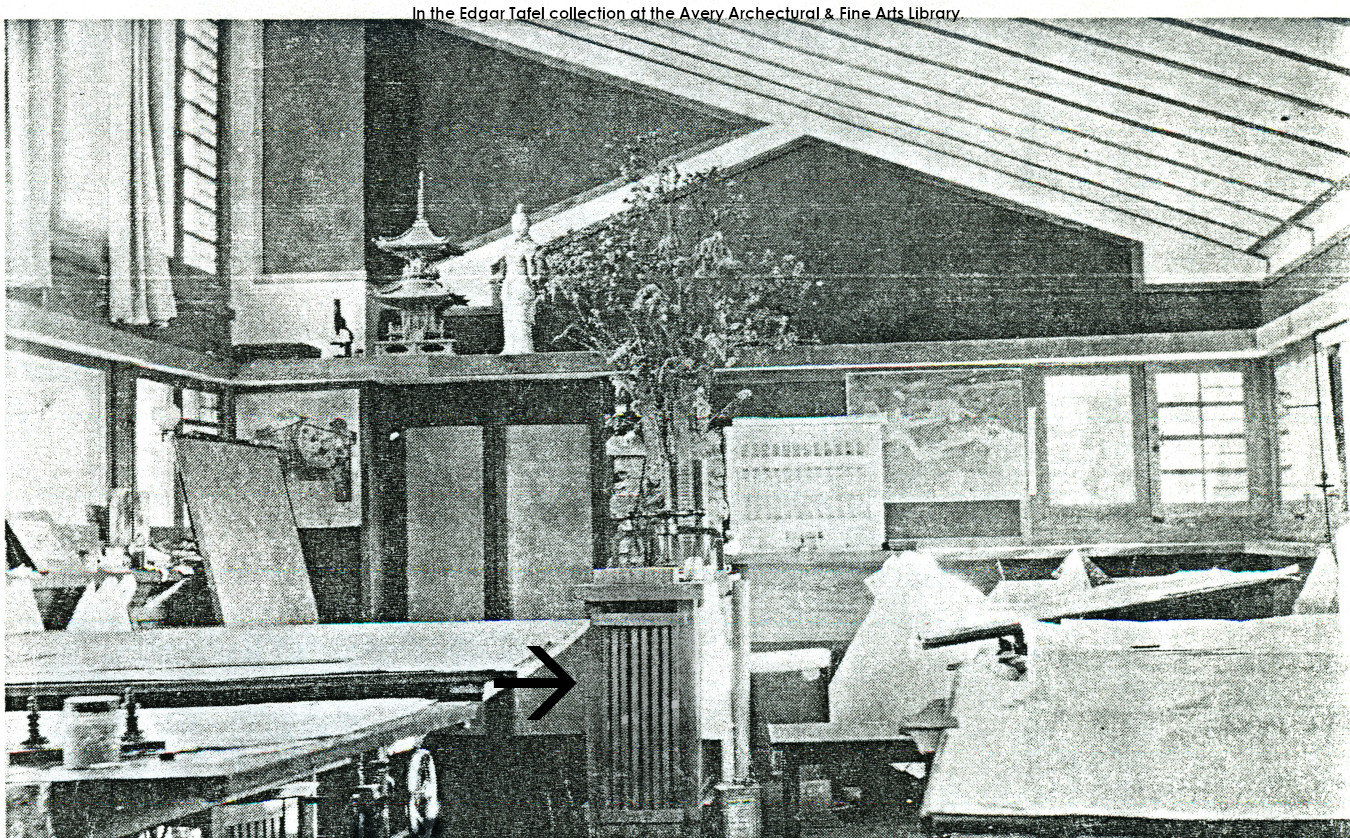

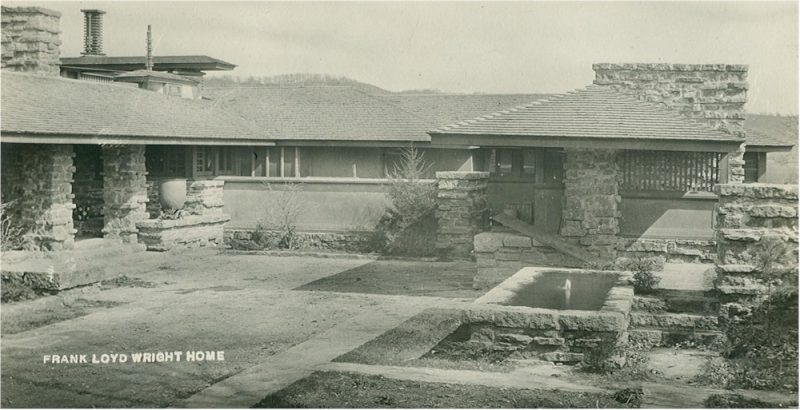

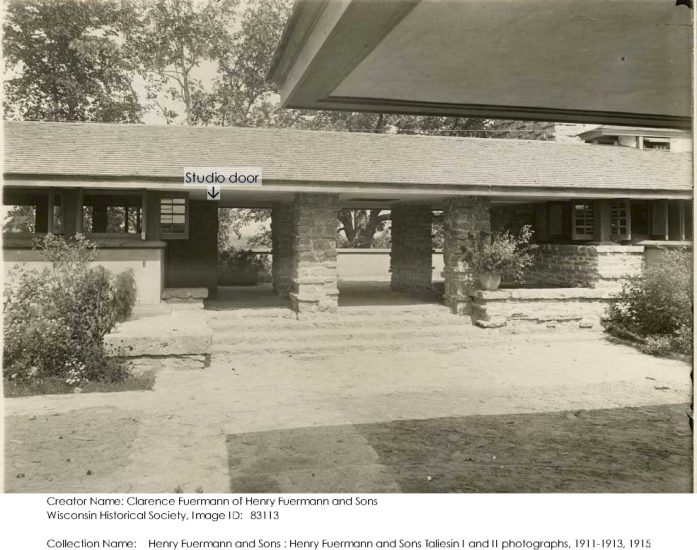

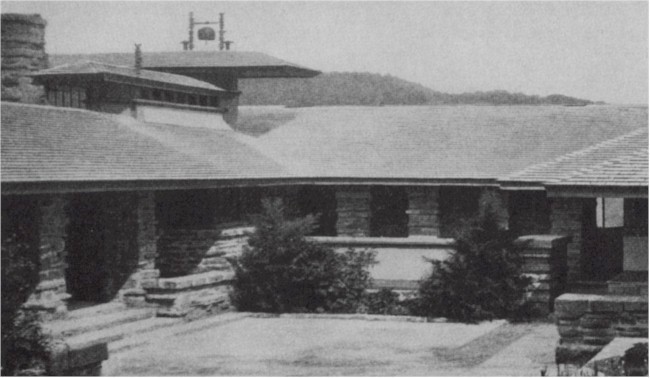

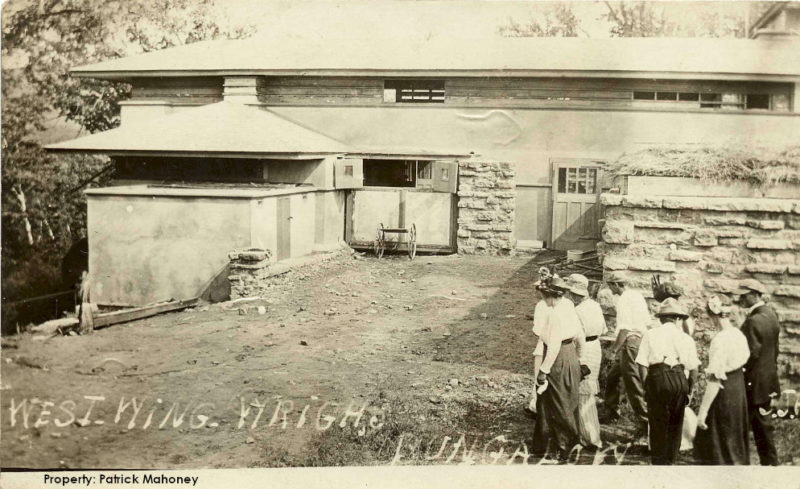

Wright placed the cow barn under Taliesin’s original hayloft. I’ll point you to the area in the photo below, taken in 1912:

Collection: Henry Fuermann and Sons Taliesin I and II photographs, 1911-1913, 1915.

Looking west. Taliesin’s hayloft, the horizontal part of the building under the roof, is in the background. Further beyond that is a cow with a baby calf. They’re past where Taliesin ended at that time.

At the ground level,

under the hayloft, you see the outline of a stone pier under the left-hand side. The stone pier is on the south wall. Now, Wright changed this area, but I don’t know when. However, you can see the change in the stone, like in the photo that I took, below:

Looking (plan) southeast. I took this on August 12, 2005.

If you look at the stone wall, I drew over the two vertical lines in the stone that show change. The arrow on the top is pointing out a wooden window. The window must have been put there fairly early because it shows up in a photograph from 1914. I posted about it in my second part of “What is the oldest part of Taliesin“. I’ll show that photo again:

Unknown photographer.

A postcard looking (plan) northeast at the western façade of Taliesin’s hayloft, summer (the hayloft is under the roof). Because the collection of people are unexpected at a farmhouse, Randolph C. Henning (who put this postcard in his book about Taliesin postcards), thinks this was taken the day after Taliesin’s 1914 fire and murders.

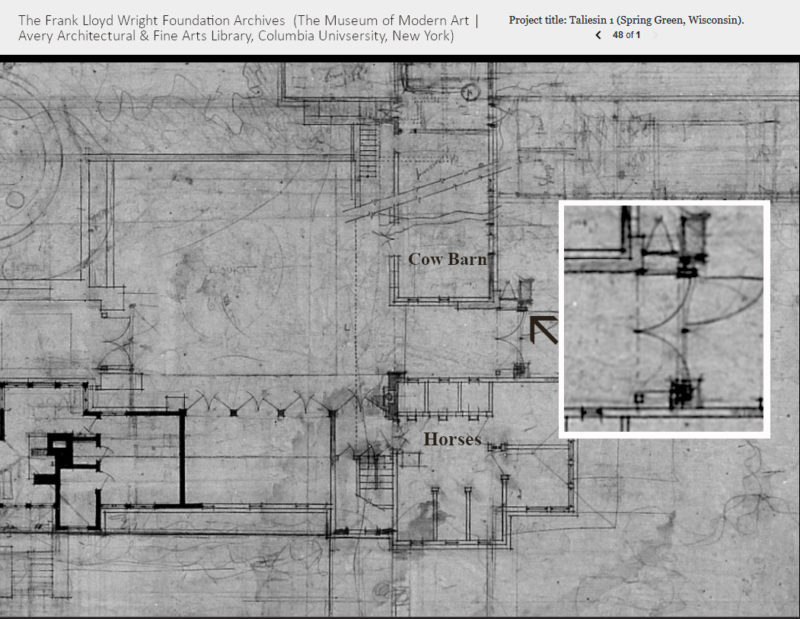

I don’t know why he did this, but a change appears in a drawing.2

That drawing is below.

I expanded the stone pier in the drawing:

On the drawing, you can see where I wrote the words “cow barn”. At the corner on the right in the cow barn, you can see the drawing of a door swinging inward. The pier to the right of that door is hand drawn.

Here’s my thought: maybe he expanded the cow barn and added the door there. But I don’t know why. Then he didn’t need it anymore so he covered it up.

Now, the last thing –

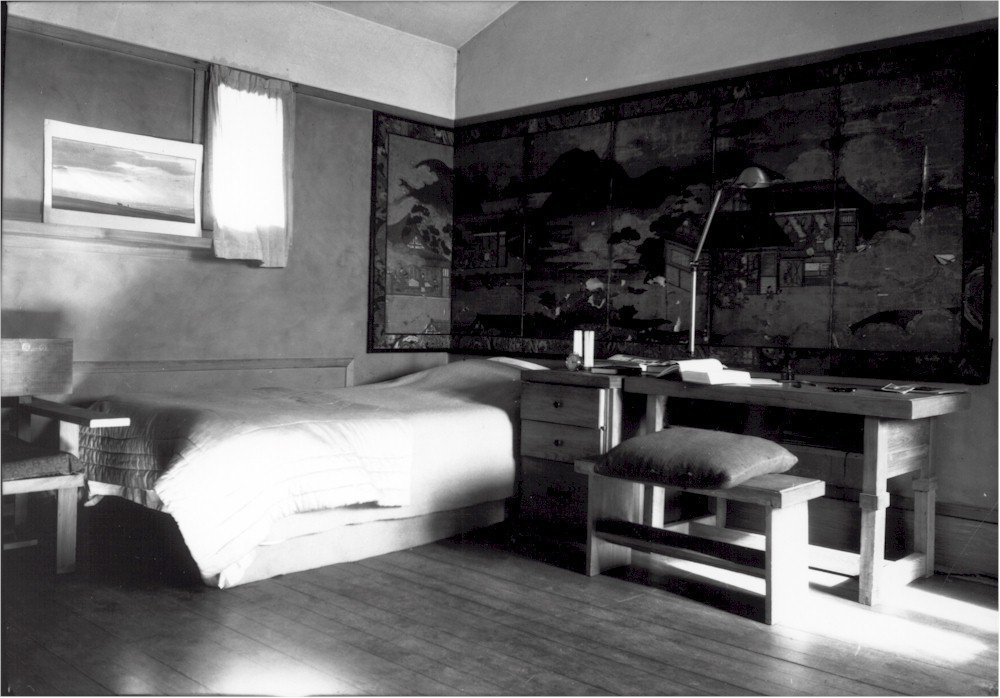

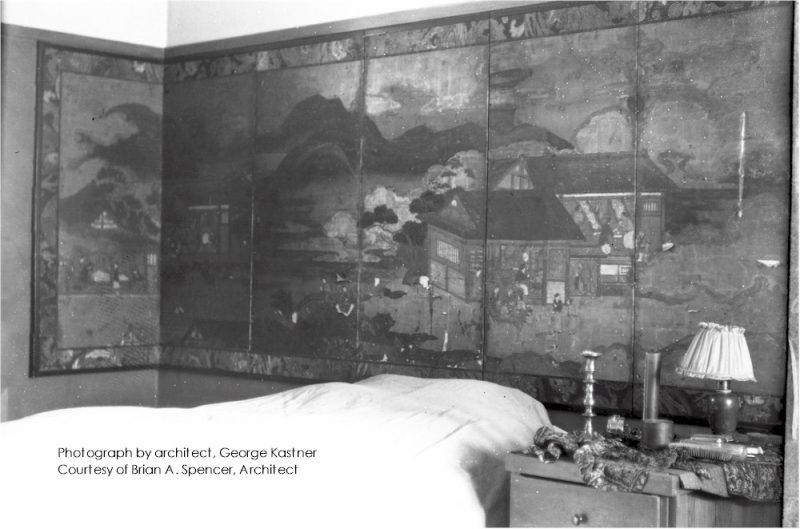

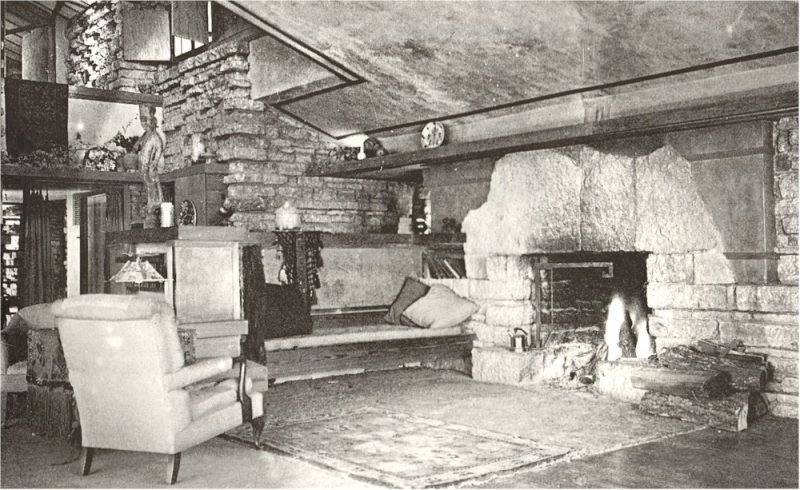

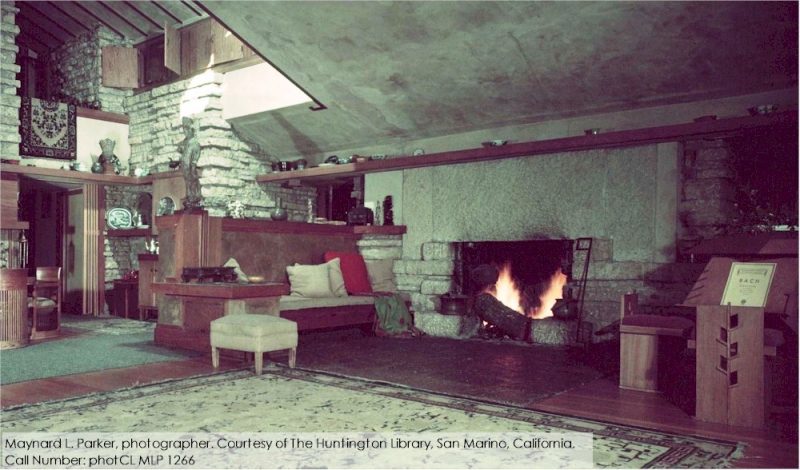

This was at Taliesin in the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s.

This is a change that makes me go, “Uh… Mr. Wright?…

“wth are you doing?”

For reasons that I do not know,

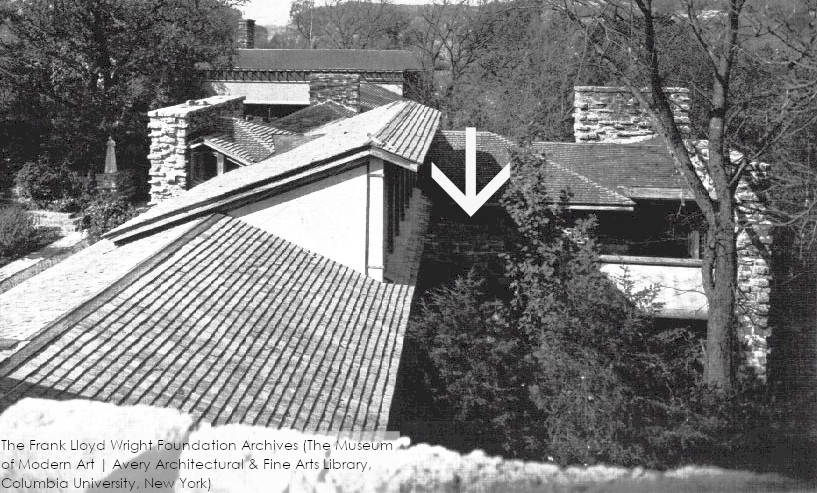

Frank Lloyd Wright removed the wall corner one floor under Taliesin’s living room.

That wing of the building was rebuilt after Taliesin’s 1925 fire.

But later Wright removed a portion of the supporting wall at the corner on the ground floor of Taliesin’s living quarters.

For years.

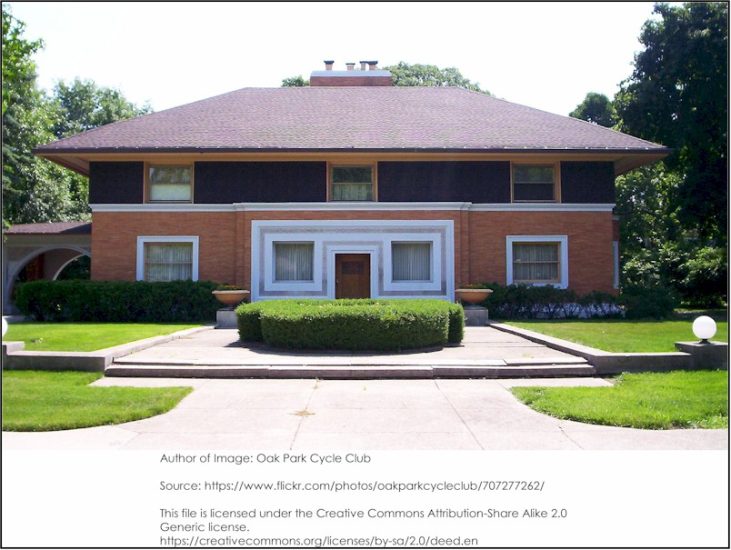

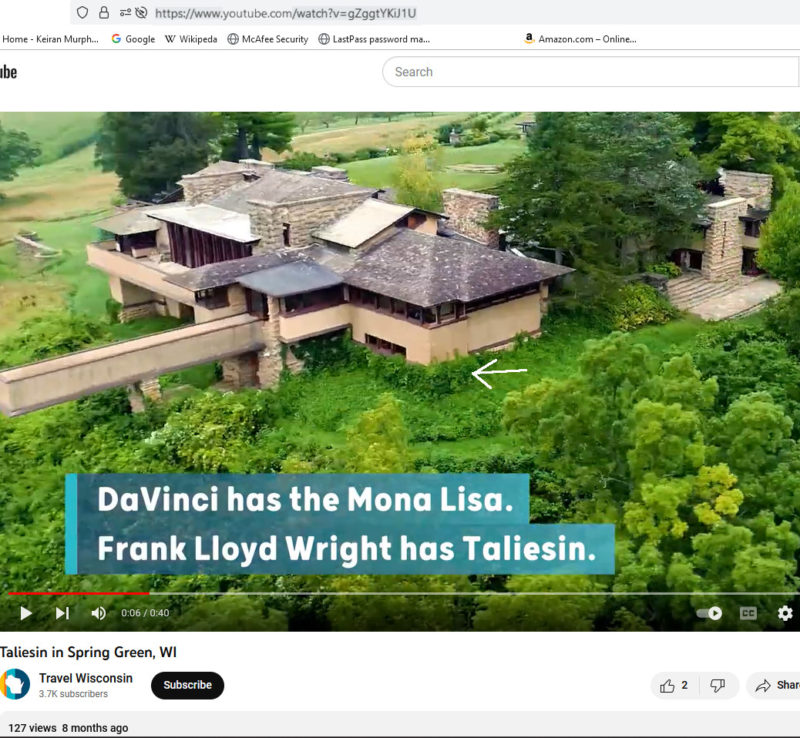

Then, he changed it back to what it looks like today, with a foundation at the ground and walls, like you can see in the drone footage below:

This photograph comes from the drone footage in “Taliesin in Spring Green, WI”. That’s available on Travel Wisconsin’s YouTube page.

Well, except for the ivy growing on the stone. Man! stuff grows so much in a Wisconsin summer.

So here’s what happened:

Wright rebuilt Taliesin in 1925 after that second fire, and the building looked like it does now. Then, for some reason, he removed a corner on the first floor of that wing.

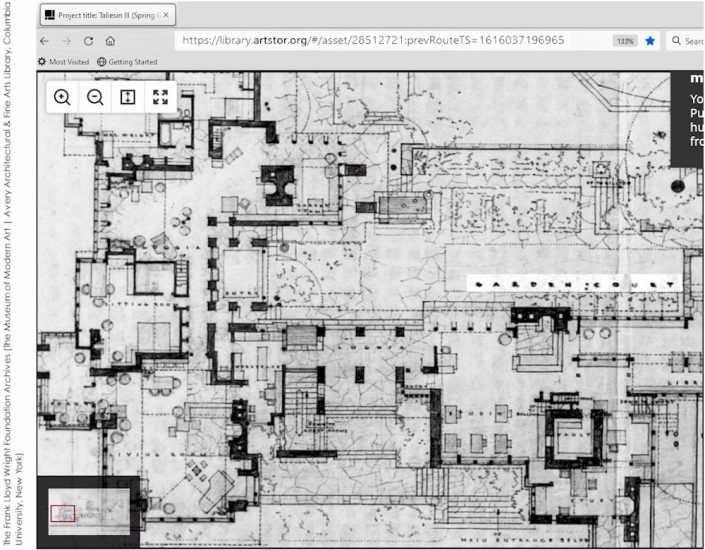

So, the corner of the building, under Taliesin’s Living Room, was cantilevered. It shows up in a drawing better than it shows up in most photos.3 Check out the drawing, #2501.015:

[Yeah yeah yeah: I know I tell you to not trust Taliesin’s drawings …. Unless I tell you to trust the drawings.]

It looks like that corner cantilevered there by 1936.

I theorize this based on photographs taken by Edmund Teske in 1936 while at Taliesin. Teske’s photographs show changes around that area of Taliesin’s north façade. It’s occurred to me that maybe Wright was checking on cantilevering? It’s not like he’d never done it before….

Maybe he was thinking about something else?

This is why

I never ask those questions (“why did he do that?”). Still, I’ve had this one question—regarding this cantilever—for… 15 years?

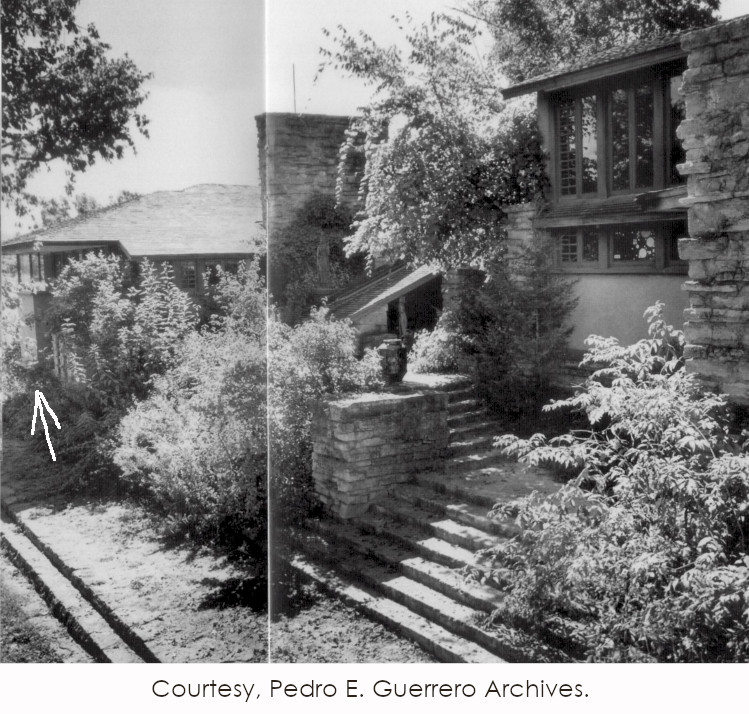

Anyway, I’ll try to show it to you. The good thing is that photographer Pedro Guerrero took a photograph at Taliesin in the early 1950s in which you can see the cantilevered corner, hidden underneath the summer growth.

This photograph was published in the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly magazine (v 8, n 3, Summer, 1997), p. 16-17. Here’s my copy of the photo:

You can find this photograph at Guerrero’s website. You click on the portfolio for Guerrero’s Taliesin photographs and keep clicking through until you come to it.

Although the reason why Wright changed it back is clear:

it has to do with sculptor Heloise Christa.

“Heloise” was a member of the Taliesin Fellowship for almost 70 years.

In 1990, she told the Administrator of Historic Studies of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Indira Berndtson, that Wright changed that corner in 1957. She knew that because the change was under Wright’s direction the year that she became pregnant with her son, Christopher.

Wright wanted to open up the space on the floor where Heloise lived so she had room with Christopher.3

First published May 14, 2023.

My thanks to Brian A. Spencer for allowing me to publish the photographs taken by George Kastner. That includes the one at the top of this post.

Notes

1. It wasn’t called the Front Office in Wright’s lifetime. It was sometimes referred to as the “back studio” (its space flows from Taliesin’s Drafting Studio to the east).

2. wow: something at Taliesin that exists in a drawing. It’s rare, but you can trust Taliesin’s drawings. Sometimes.

3. I know – once again a drawing at Taliesin seems to match reality. Strange stuff. For me, anyway.