Reading Time: 9 minutesAlexander Woollcott with Frank Lloyd Wright outside of Taliesin.

a room that existed before we (or I) knew it existed.

I’m going to write about my discovery of that room’s appearance today. It’s the room with the windows that you see behind Wright, Woollcott, and the birch trees.

It was thought that the room was originally designed for Wright’s youngest daughter Iovanna (born to Olgivanna in December 1925).

Meryle Secrest wrote in her Wright biography that in March 1925, Wright and Olgivanna “made an impulse decision to start a family of their own.” [Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography, 315]

Secrest gave no evidence for this “impulse decision”. Obviously something impulsive happened and Olgivanna was young and pretty, so I’m like, “Yeah… Sure.”

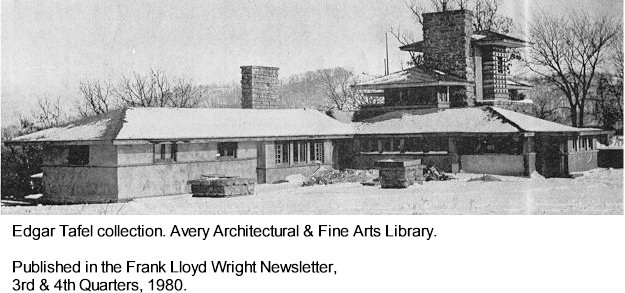

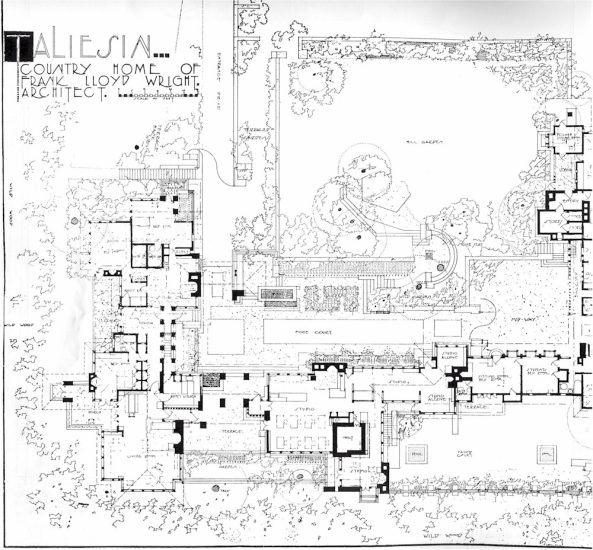

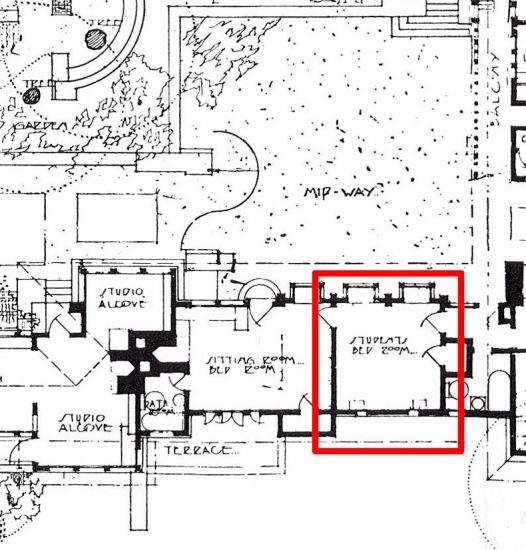

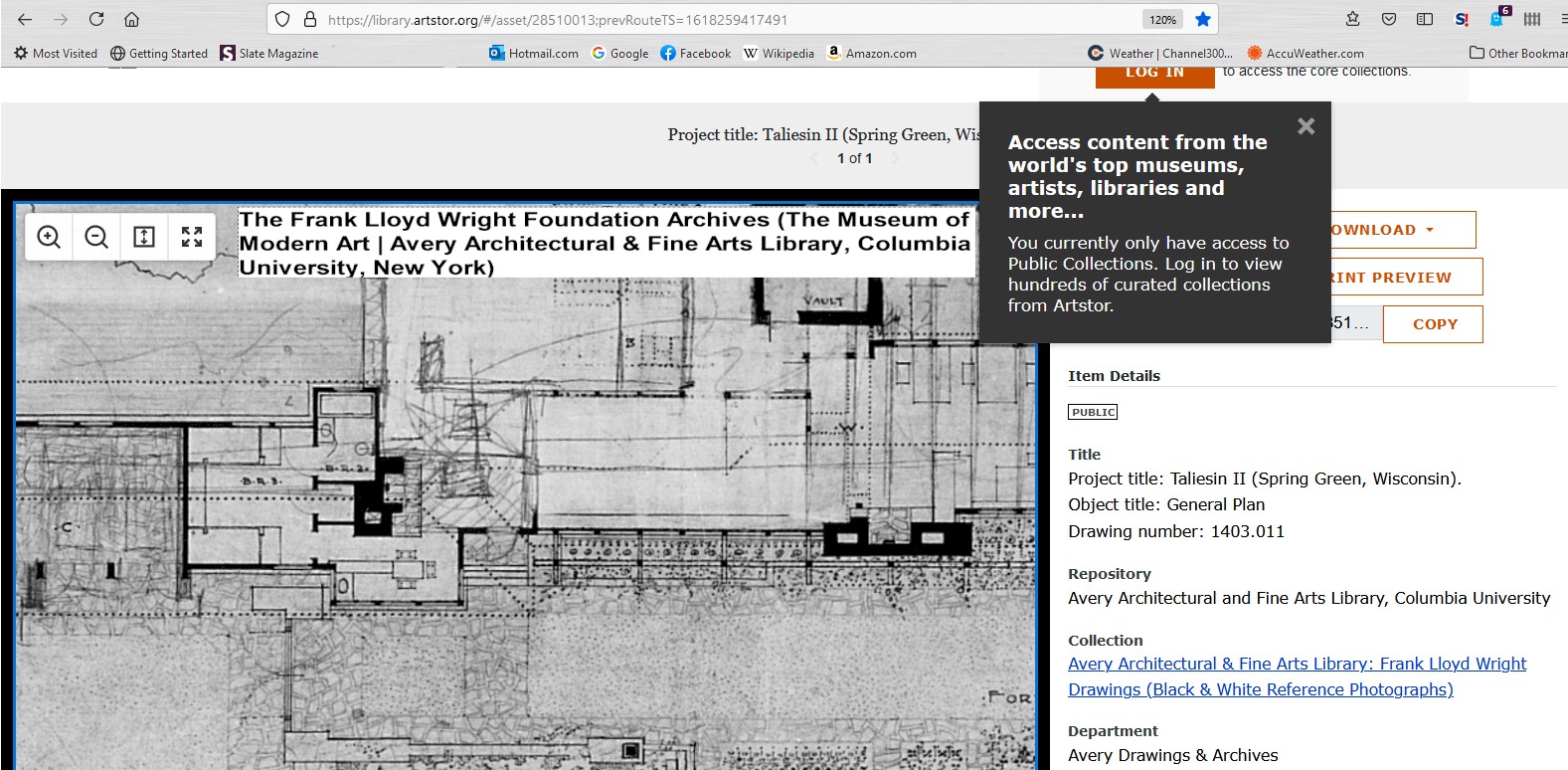

Here’s where it is:

The room is one floor above Olgivanna’s bathroom, so you walk by it as you go into her room on a tour through Taliesin.

FYI: The bathroom was dismantled, so it’s not on tours.

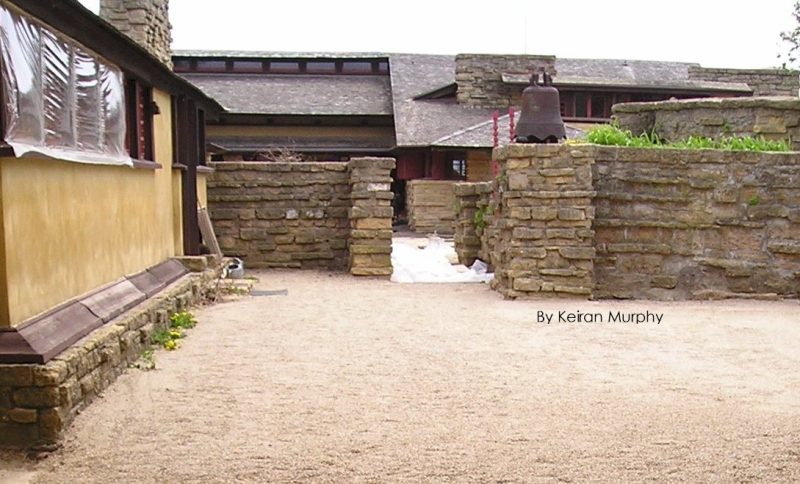

You can see the outside of Iovanna’s sitting room when you’re on the Hill Crown at Taliesin. Wright added the parapet1 which you can see in this photo I took:

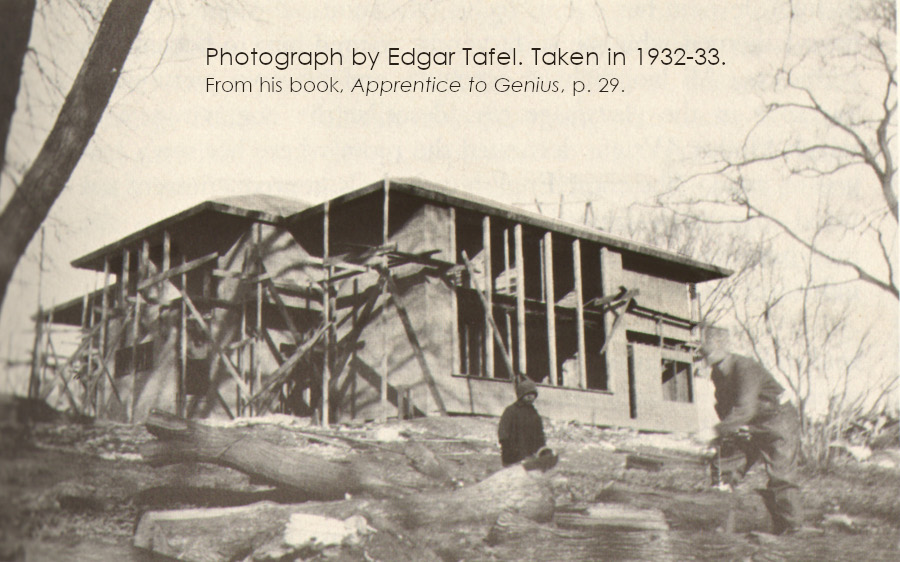

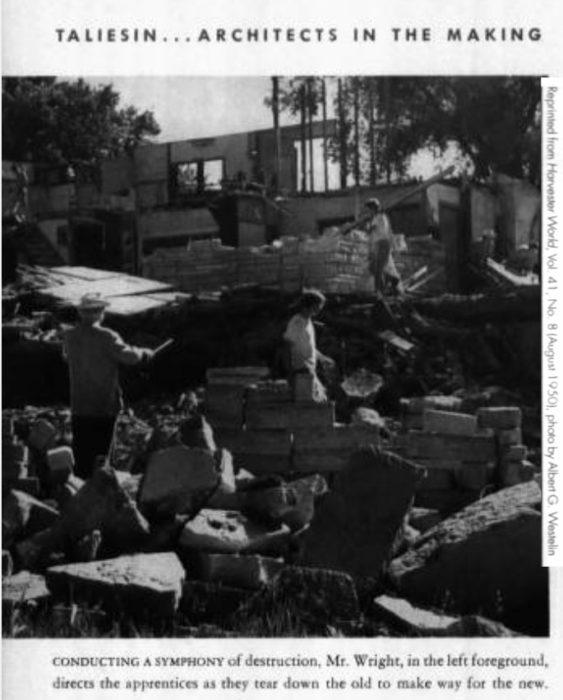

Taliesin Fellowship apprentices did the construction of the rooms in 1933-34. Abe Dombar wrote about it in this February 9, 1934 article:

Two new rooms were added to the pageant of Taliesin’s 40 rooms merely by lowering the ceiling of the loggia and raising the roof above it to get the most playful room in the house. The boys call it a “scherzo.” This is little eight year-old Iovanna’s room.

Several new apprentices, with the aid of two carpenters, were working on the job continuously from the architect’s first sketch on a shingle to designing and building in of the furniture. And the girls made the curtains. In celebration of the completion of the room we had a “room-warming” in the form of a surprise party for Iovanna.

Abe Dombar. “At Taliesin,” February 9, 1934. Reprinted in At Taliesin: Newspaper Columns by Frank Lloyd Wright and the Taliesin Fellowship, 1934-1937, ed. by Randolph C. Henning, (Southern Illinois University Press, 1991), p. 20-21.

It makes you think:

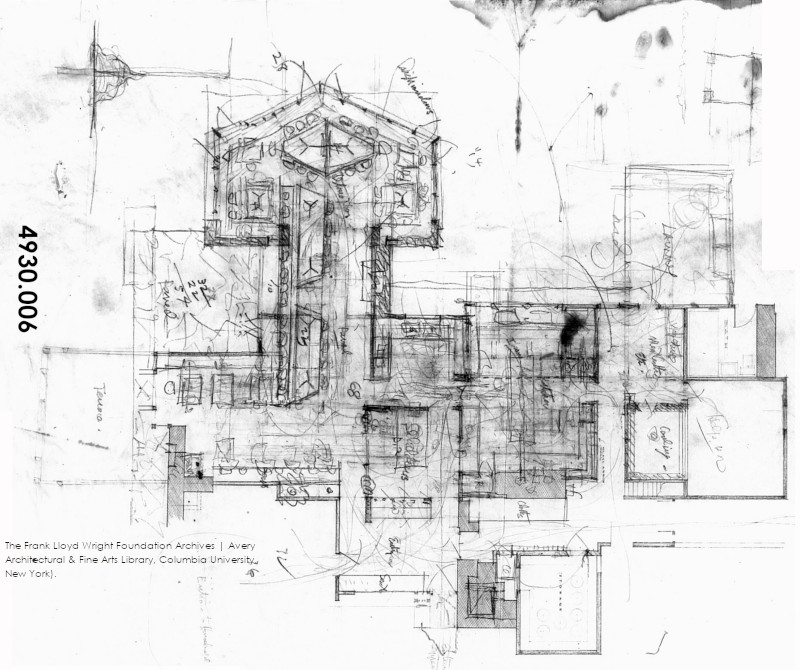

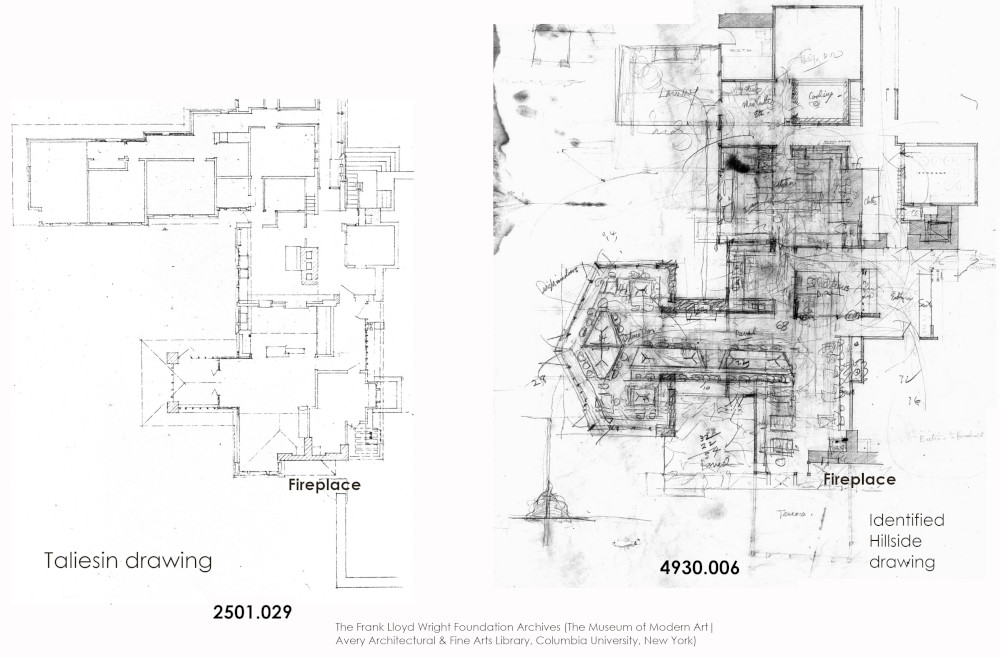

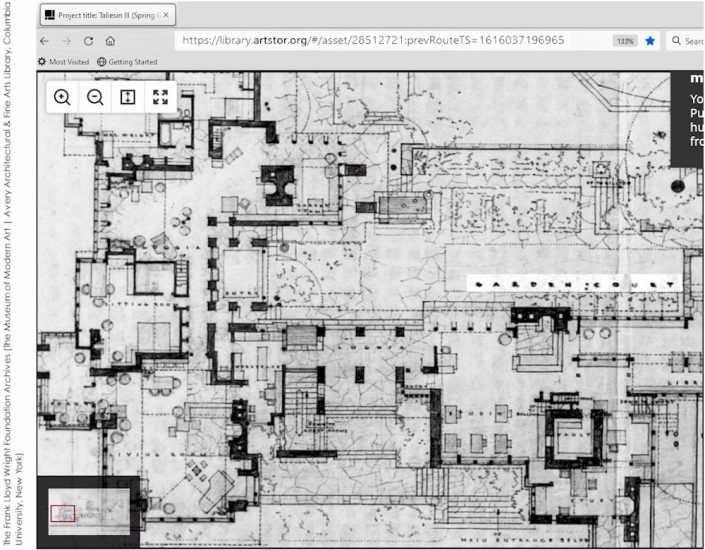

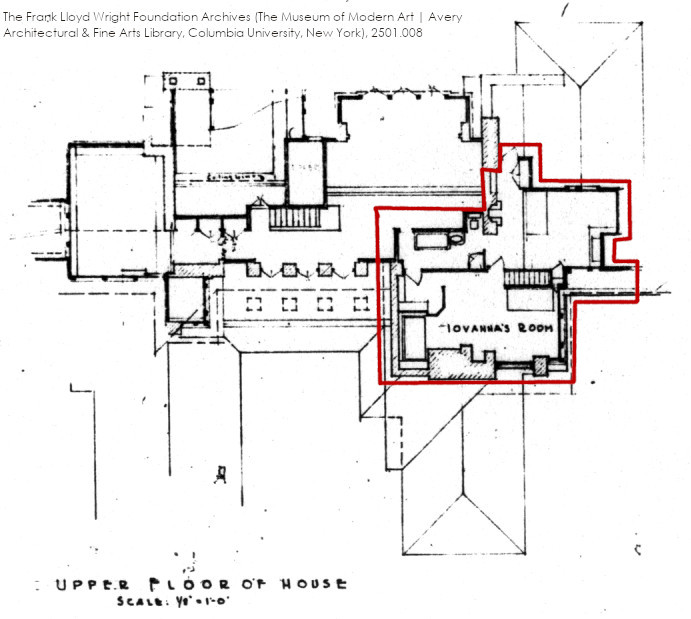

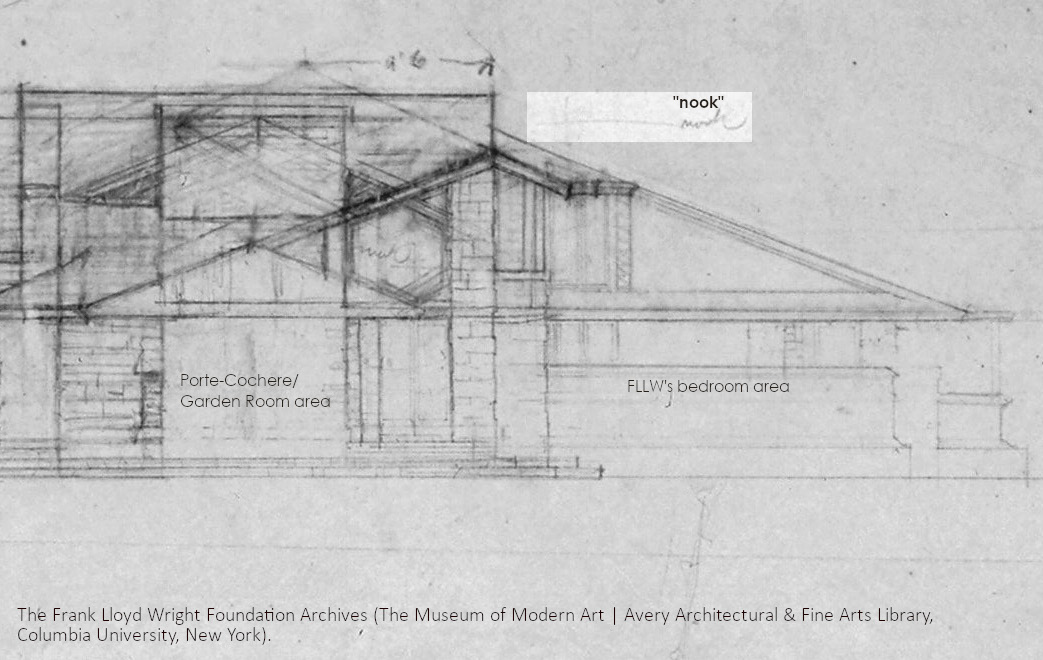

While kids may have been more hardy in the past, that is a lot of space for a little girl. Here’s one drawing that shows it:

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York), #2501.008.

Although the rooms in the 1930s were smaller, there was still a bedroom, sitting room, and bathroom.

That makes sense

when you think of the playroom he scaled down for his kids in his first home in Oak Park, Illinois.

I was told years ago that it was originally scaled down for Iovanna when she was 8, but I’ve never seen an interior photo taken at that time.

Not that this would matter anyway. Remember: Wright’s building scale already messes with your mind.

However,

The number of rooms is also due to things happening in the Wright family.

See,

when the Wrights started the Taliesin Fellowship in 1932, Olgivanna’s oldest daughter, Svetlana (“Svet”), was 15. So the next summer, Wright designed those bedrooms for both Svet and Iovanna (then 7 years old).

But things got complicated.

One of those complications was related to one of the first Taliesin Fellowship apprentices: Wes Peters.

No doubt

Olgivanna made sure to keep her pretty young daughter away from all of the architectural apprentices in 1932 and ’33. But it was all intense and, even if you had them working 15 hours-a-day, young is young and those two (Wes and Svet) fell in love.

They wanted to get married and Svet’s parents said absolutely not.

And, yes, Frank Lloyd Wright fell in love with Catherine Lee Tobin when he was, maybe 19-20 (Kitty was 16-17); and Olgivanna got married when she was 19, but the marriages for those two ended in divorce, so….

But, come on:

check out the screenshots from the film apprentice Alden Dow made in 1933, the first summer those two knew each other. They’re so cute:

The movie is the property of the Dow Archives, but you can see it in sections through this link.

So, in September 1933,

Wes and Svet left the Fellowship, even though Svet couldn’t get married until she was 18. You can read about their history in this book, “William Wesley Peters: The Evolution of a Creative Force“.

Svet’s age (15 or 16), gets me scandalized, but then again: I’m no longer a teenager.

I mean: I was completely bummed when—in grade school in the spring of 1980—I found out that Sting was 28 years old and married. But then I realized that, “uhh… Keiran? Sting’s not waiting for you.” [I may remember this moment because I was surprised by that grown-up thought].

You can read my teenage thoughts about Sting in my post: “Dune, By Frank Herbert“. I wrote this about the second installment of the Dune movie by Denis Villeneuve that came out in March 2024.

To get back to Iovanna’s bedroom:

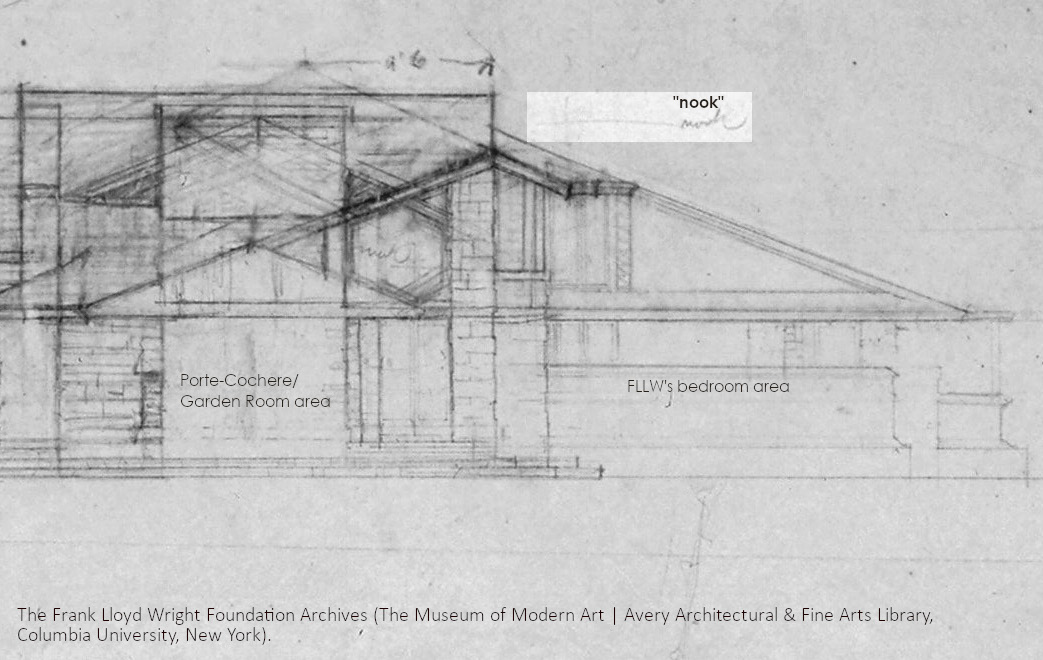

For years, we thought that before that area had rooms and a bathroom, there was just a mezzanine up there that ended above Taliesin’s Living Room.

You can see it at the top of this post.

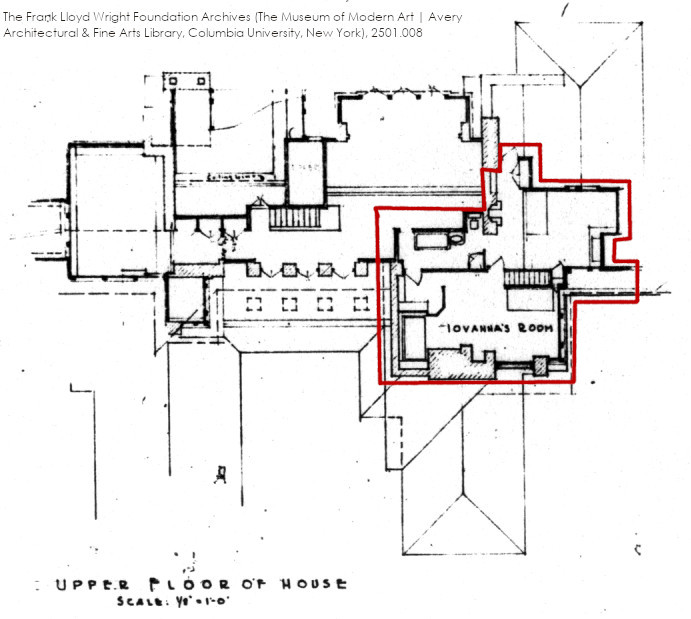

And that it ended on the other end just over Wright’s bedroom.

To picture it, you can see part of the mezzanine in this post.

However, in 2004-5, I was asked to research the entire history of that floor up there.

So I did what I usually try do:

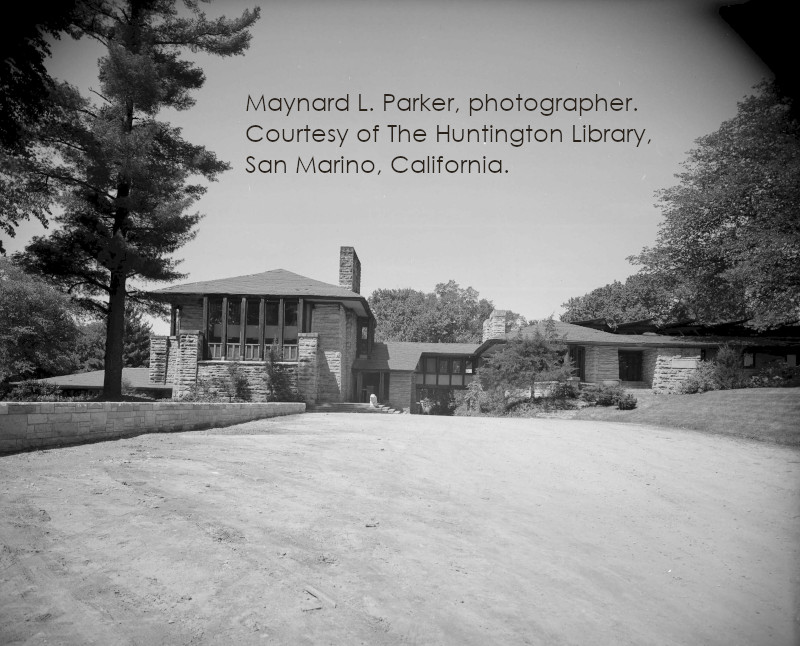

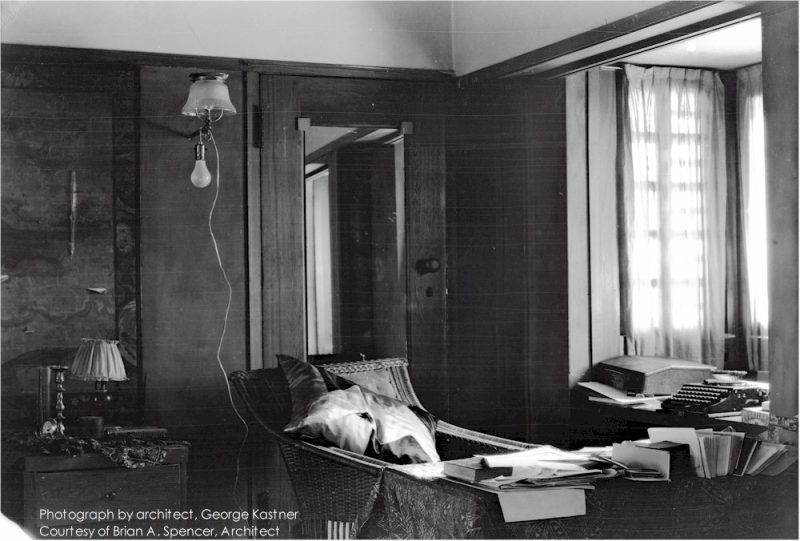

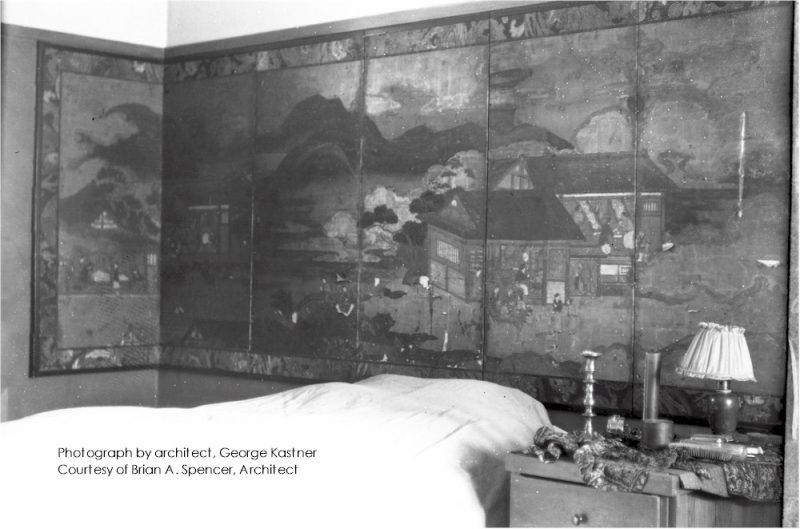

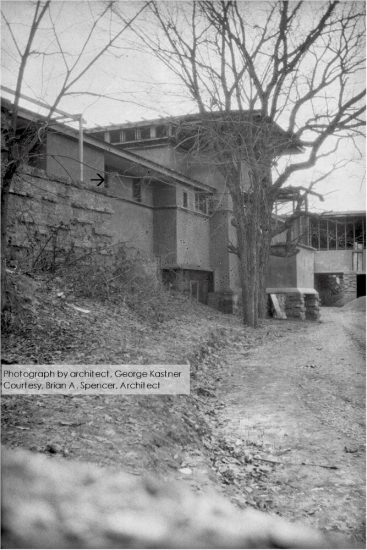

I try to wipe my mind of preconceptions2 and look at photos. And so, for the the first time, I saw something earlier photos at Taliesin that shouldn’t have existed at that time. I saw in these earlier photos a chimney flue for the fireplace that’s in Iovanna’s Bedroom. Among other photos,3 the flue appears in one taken in 1928:

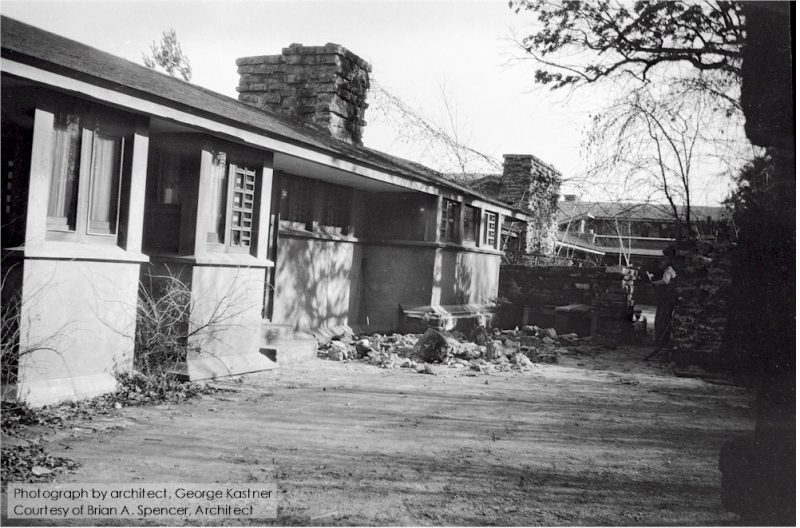

This photo is published on p. 4 in the Journal of the Organic Architecture + Design archives, Vol. 7, no. 3, 2017 in the article for that issue, “Desert and Memoir: George Kastner and Frank Lloyd Wright,” by Randolph C. Henning.

That flue I pointed out goes to only one fireplace: the one for Iovanna’s Bedroom. Yet George Kastner took this photograph in 1928, 5 years before the apprentices even started working in that area. So it didn’t match what I thought I knew. I thought that, before 1933, this stone mass was simply… stone. That it was like the stone mass that’s on the south side of Taliesin’s living room. That this part was only stone.

Like what was in Hillside’s Dana Gallery on the Taliesin estate that I wrote about in “Truth Hiding in Plain Site“. That it was mostly stone before the Taliesin Fellowship.

But since I couldn’t deny what was in photographs,

I got in my car and drove to Taliesin to see what I could find.

I went upstairs, looking for evidence that things had changed. First thing I noticed was that the stone was executed at one time, as opposed to being changed later. See my photo of the fireplace below:

Contrast this

With the fireplace in the adjacent room. In 1933-34, Apprentices built that fireplace out of the existing chimney. And it certainly looks like it.4

I took the photo below where you see the side of the chimney. On the left hand side you see stone that used to be outside. The red stones were those that went through the Taliesin fires in 1914 and 1925. The lighter stone on the right is stone placed there by apprentices when they built the fireplace mantelpiece:

After looking at the two fireplaces, I thought about that “At Taliesin” article. In the article, Abe Dombar says,

Two new rooms added to the pageant of Taliesin’s 40 rooms….

But there weren’t two rooms on that floor in 1934. There were three: Iovanna’s bedroom, the bathroom, and the sitting room (the room at the newer fireplace).

In fact, the drawing doesn’t label Iovanna’s bedroom. It only labels “Iovanna’s room”, which is the sitting room with the new mantelpiece.

And one more thing: the bathroom

You can see the bathroom in the plan above. When I started thinking maybe Iovanna’s Bedroom was there before 1933-4, I thought how it doesn’t make a lot of sense for Wright to build a bathroom out of line with the bathroom one floor below. Often bathrooms are in line with each other because this makes laying the plumbing lines easier.

yeah, yeah, yeah: we can talk about how impractical Wright could be as an architect, but at Taliesin he had to live with whatever he designed. And bathrooms are expensive, even if the labor was free….

Moreover,

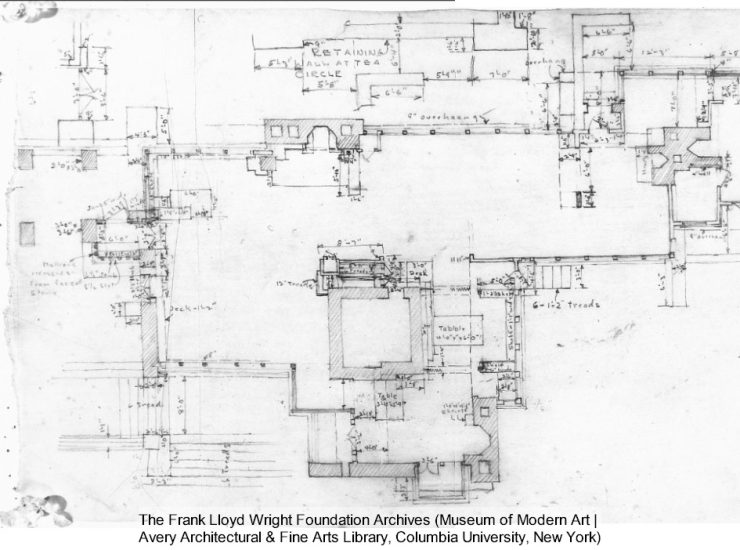

in 2007, I looked at Taliesin’s drawings for real in Wright’s archives. Luckily for me, Taliesin’s estate manager suggested I take photocopies of Taliesin’s drawings so I could take notes on what I saw in them.

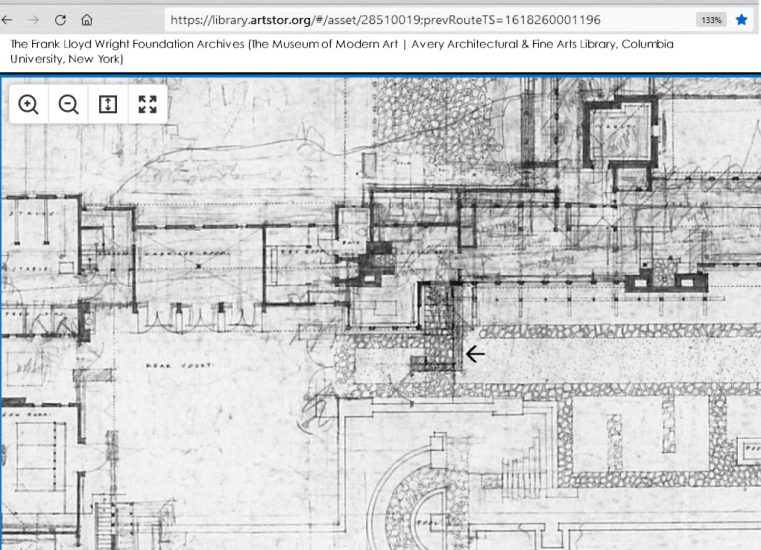

In drawing #2501.007, I saw the word “nook” in pencil with a line going about where Iovanna’s Bedroom was:

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York), #2501.007.

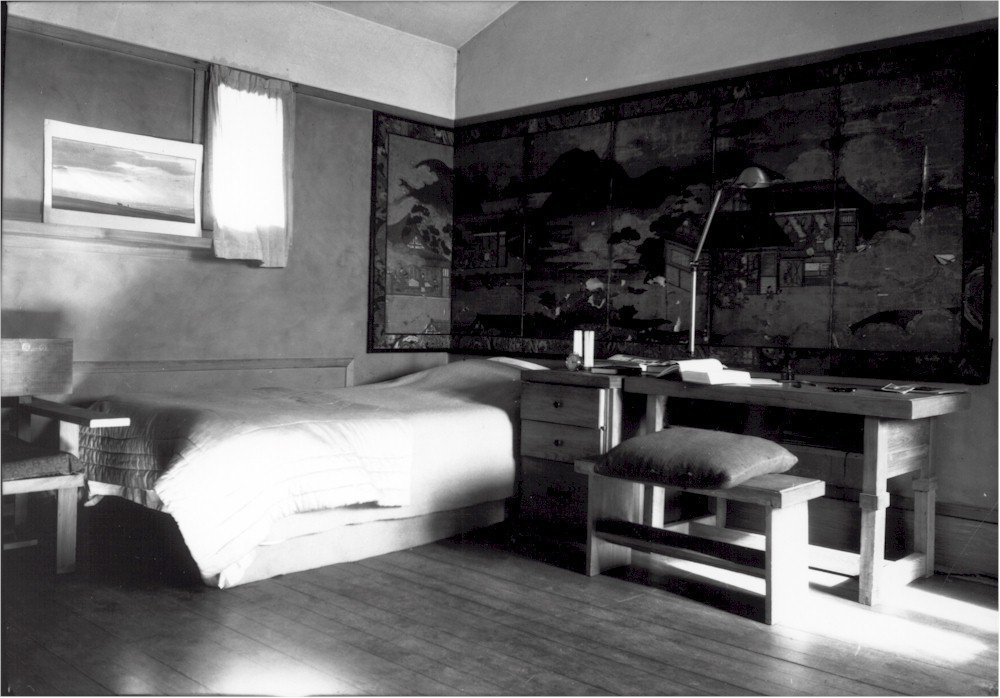

I can’t tell you when 2501.007 was drawn, but the details say 1925-32. I think that in the early Taliesin III period, what became Iovanna’s Bedroom was originally a sitting room, a “nook”, that could be used as a bedroom if needed.

alas, we don’t have Wright’s design for the couch/bed simplicity of a futon frame

3 more things:

coz: in for a penny, in for a pound

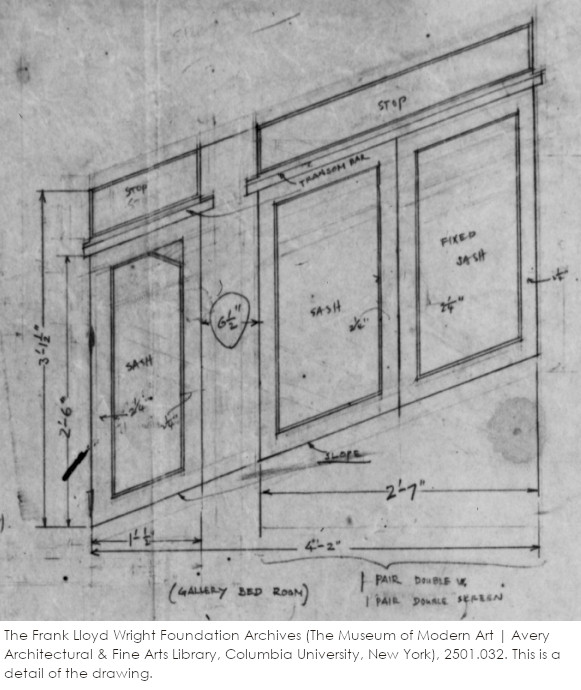

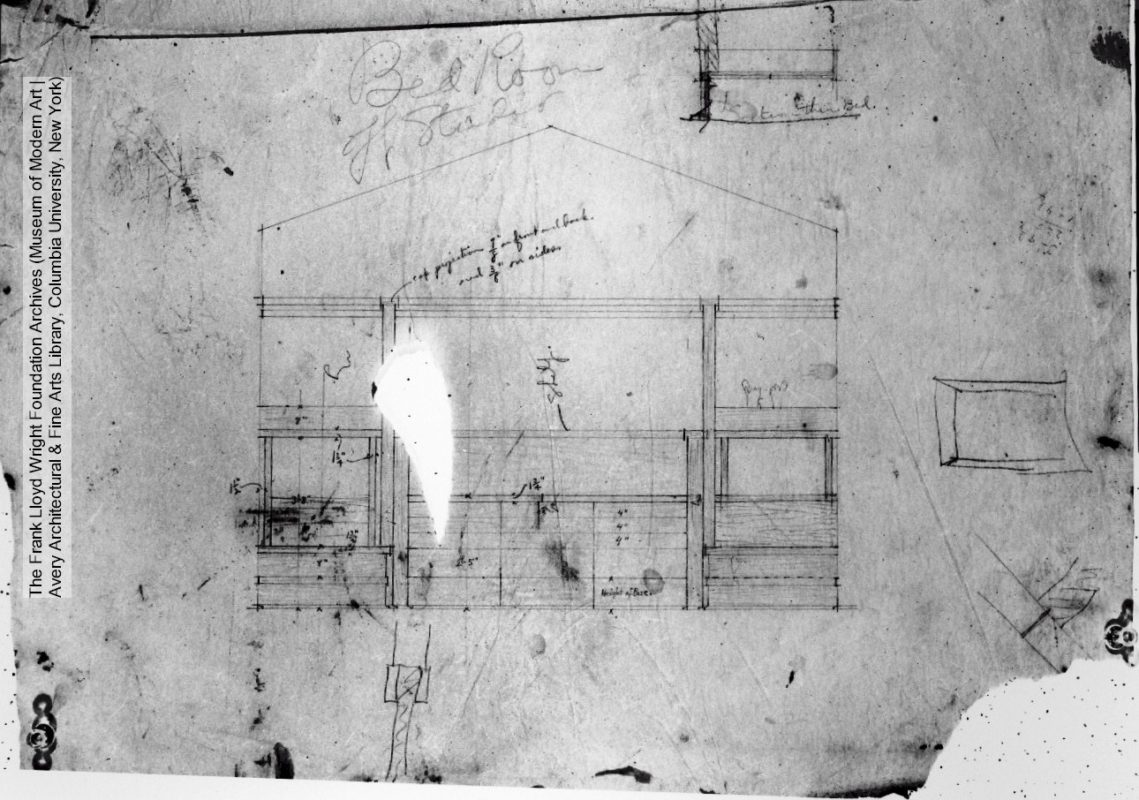

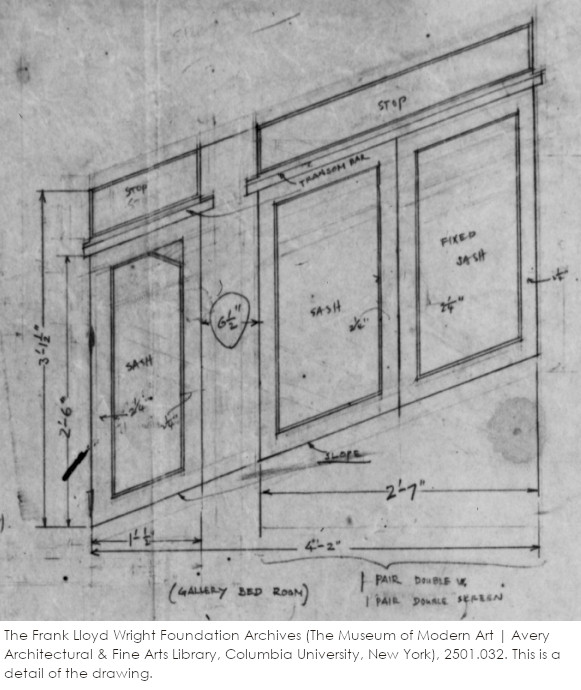

One Taliesin drawing shows the “sash details” of the windows in Taliesin’s Living Quarters. This is drawing #2501.032. See the detail of it below:

The three windows I pulled out from the drawing match the three windows currently on the east wall of Iovanna’s Bedroom. The drawing labels these windows as being for—not a clerestory or above the mezzanine, but—”Gallery Bed Room”.

Also, in 2006

The Taliesin Preservation crew worked in a closet in Iovanna’s Bedroom and found remnants of pipes going through the floor above Olgivanna’s bathroom. I asked what those pipes could be, and one crew member (I forget who) said they were small enough to be used for a sink, but not a toilet or tub.

Wright could have had this little room up there and if someone were just staying overnight, they could use the sink in the morning to brush their teeth.

One of those people might have been architect Philip Johnson

See, back in the 2000s someone emailed me at work. He was working on a book of interviews conducted by architect Robert A.M. Stern with Philip Johnson.

Stick with me here

At one point, Stern talked to Johnson about Wright:

Robert A.M. Stern: And in researching for the book [on the International Style] you also went to visit Wright?

Philip Johnson: …. We went to see Wright in 1930 in Taliesin East [sic].5 I stayed overnight in the part that’s now all closed in and ruined, in the upper terrace there, just above the big room. We visited and had a great time and we realized that he was a very, very great man.

The Philip Johnson Tapes: Interviews with Robert A.M. Stern (The Monacelli Press, printed in China, 2008), 41.

The book’s price tag is over $40, but I’m that crazy: I got the book on sale for $10.

He mentions “the big room”. In 1930, there wouldn’t have been any other “big room” on the Taliesin estate except for the Taliesin Living Room.6 He was wrong about the placement of the room on that floor, but there was nothing else up there in 1930 that matches it.

OK!

I hope I explained what I found/think.

That is:

When Wright rebuilt his living quarters after the 1925 fire, he built a mezzanine above the main floor that ended in a small room with its own fireplace, three windows on the east wall, and windows (or possibly French doors) on the other side.

The windows above and behind where Alexander Woollcott and Frank Lloyd Wright are standing in the photo at the top of this post might have looked into this “nook”.

The photo at the top of this post was taken 1937-41 and published in Apprentice to Genius: Years with Frank Lloyd Wright, by Edgar Tafel, p. 179.

First published October 22, 2023.

Notes

1. He expanded the space and added the parapet in 1943 for an anticipated visit by Solomon Guggenheim (of the Guggenheim Museum commission) and curator, Hilla Rebay.

2. Which I remember every damned time I think about the window found in Taliesin’s guest bedroom that was staring me in the face for years in photos. I’ll write about it another time to go over it in detail. It’ll be penance.

My Penance Post is at “Another Taliesin mystery that I missed“

3. I think I first noticed it in a photo that I can’t show because I don’t think it’s ever been published. It’s Whi(x3)48218, an aerial photograph in the Howe Collection at the Wisconsin Historical Society.

4. Her personal spaces were featured in a Wright Virtual Visit in 2021, which is on Facebook, here.

5. Johnson was wrong on when he and Hitchcock visited Taliesin. According to Wright on Exhibit, the book by architectural historian, Kathryn Smith, they came in June 1932. Wright on Exhibit: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Architectural Exhibitions, by Kathryn Smith (Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 2017), 83.

6. It wasn’t at Hillside because Johnson said they visited it and while it was a great building, he described Hillside in 1930 as “a total wreck”.