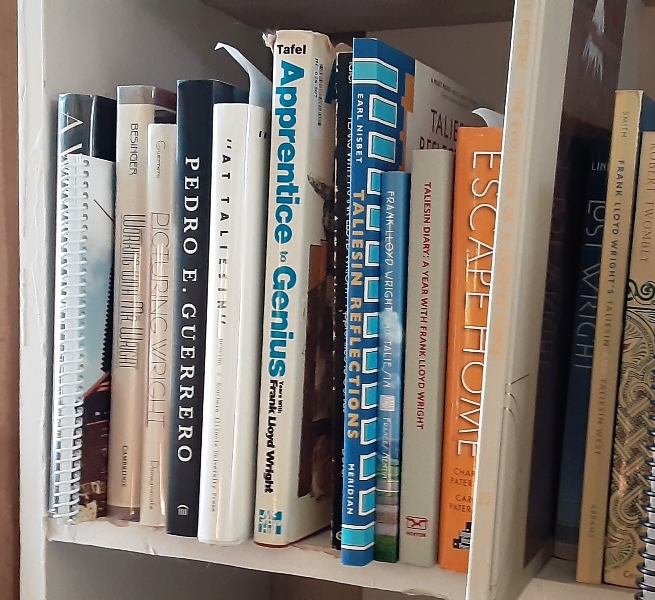

Last time I wrote on the book Years With Frank Lloyd Wright: Apprentice to Genius by former Wright apprentice, Edgar Tafel. This week I’m writing about more books by Taliesin Fellowship apprentices.

If you need to remember what the Taliesin Fellowship is, click here

Memoirs by former apprentices:

Reflections From the Shining Brow: My years with Frank Lloyd Wright and Olgivanna Lazovich Wright, by Kamal Amin

Amin came from Egypt to join the Fellowship in 1951 and remained until 1978. Amin gives a unique view about Frank Lloyd Wright, and his wife, Olgivanna.

Working with Frank Lloyd Wright: What it was Like, by Curtis Besinger

This is a nice companion to “Apprentice to Genius”. Besinger became a Wright apprentice in 1939 and stayed until 1955. He brings you year by year through his experience at Taliesin in Wisconsin in the summer, and Taliesin West in Arizona in the winter. He also discussed projects through the years, like the Unitarian meeting House in Madison. Additionally, he talked about activities in the Fellowship: movies the group saw, and about playing and practicing music. And the author wrote about the effect of World War II on the group.

See the book below (A Taliesin Diary, by Priscilla Henken), for the day-to-day Fellowship life during World War II.

Tales of Taliesin: A Memoir of Fellowship, by Cornelia Brierly

Cornelia was an early Taliesin apprentice, and this book contains a collection of her remembrances. Her memories are unique and often humorous. In addition, the book includes interesting photos from her collection.

Picturing Wright: An Album from Frank Lloyd Wright’s Photographer, by Pedro Guerrero

Picturing Wright shows Wright’s openness. “Pete” was 22 years old, with no experience, when he asked Wright if he could work for him. Wright, who was 50 years older, saw Peter’s talent and gave him all the work he wanted.

Check out Guerrero’s website, https://guerrerophoto.com/. This has a great collection of his photographs all through his career.

A Taliesin Diary: A Year with Frank Lloyd Wright, by Priscilla Henken

Most books by apprentices were written years later, but this was an actual diary kept at the time. Priscilla and her husband, David, were in the Fellowship (1942-43) and she wrote in her diary every day. What she saw and felt give a unique perspective on daily life in the group, and on Wright and his family. The book includes photographs taken by the Henkens when they were apprentices, that have not appeared elsewhere.

Frank Lloyd Wright and Taliesin, by Frances Nemtin

“Frances”, was in the Taliesin Fellowship from 1946 until she died in 2015, wrote this book about Wright’s design and about the Taliesin Fellowship. The book contains original photographs.

She wrote a variety of booklets about her life in the Fellowship, but this is one of the few published in hardcover.

Some of her booklets may still be in gift shop at the Frank Lloyd Wright Visitor Center, so maybe you’ll see them if you take a Taliesin tour this year.

Taliesin Reflections: My Years Before, During, and After Living With Frank Lloyd Wright, by Earl Nisbet

Nisbet was an apprentice under Wright in 1951-1953. His “Taliesin Reflections”—short scenes—are mixed with profiles of people in the Fellowship (Gene Masselink, Wes Peters, Jack Howe, and others). When Nisbet went to work as an architect, he employed lessons from Wright in his practice. The book has original illustrations and photographs.

Autobiographies by former apprentices:

Pedro Guerrero: A Photographer’s Journey with Frank Lloyd Wright, Alexander Calder, and Louis Nevelson, by Pedro Guerrero

In this book, “Pete” writes about growing up, as well as his career. He worked not only with Frank Lloyd Wright, but with two other major 20th Century artists. He photographed the sculptors: Alexander Calder and Louise Nevelson. Also, Guerrero writes about his work in the magazines House Beautiful, House & Garden, and Vogue among others (while always working at Wright’s request).

Related:

The film documentary, “American Masters — Pedro E. Guerrero: A Photographer’s Journey”, was released on PBS, American Masters, in 2017.

Escape Home: Rebuilding a Life after the Anschluss — A Family Memoir, by Charles Paterson (Author), Carrie Paterson (Author, Editor), Hensley Peterson (Editor)

Charles Paterson was in the Taliesin Fellowship from 1958-60. Truthfully, I purchased the book only for its Taliesin Fellowship connection. I read it in its entirety during the Covid-19 lock-down. So, that’s one thing to be grateful for in the year 2020.

Paterson’s life begins in the 1930s in Austria. Then, his father helped him and his sister escape to Australia during World War II. The three were alive at the end of the war and reunited in the United States. Yet, Paterson’s study under Wright was one stop before he moved to the raw Colorado town of Aspen, where he became an architect.

And all of this is without mentioning Paterson’s uncle, architect Adolf Loos!

More Than One Author:

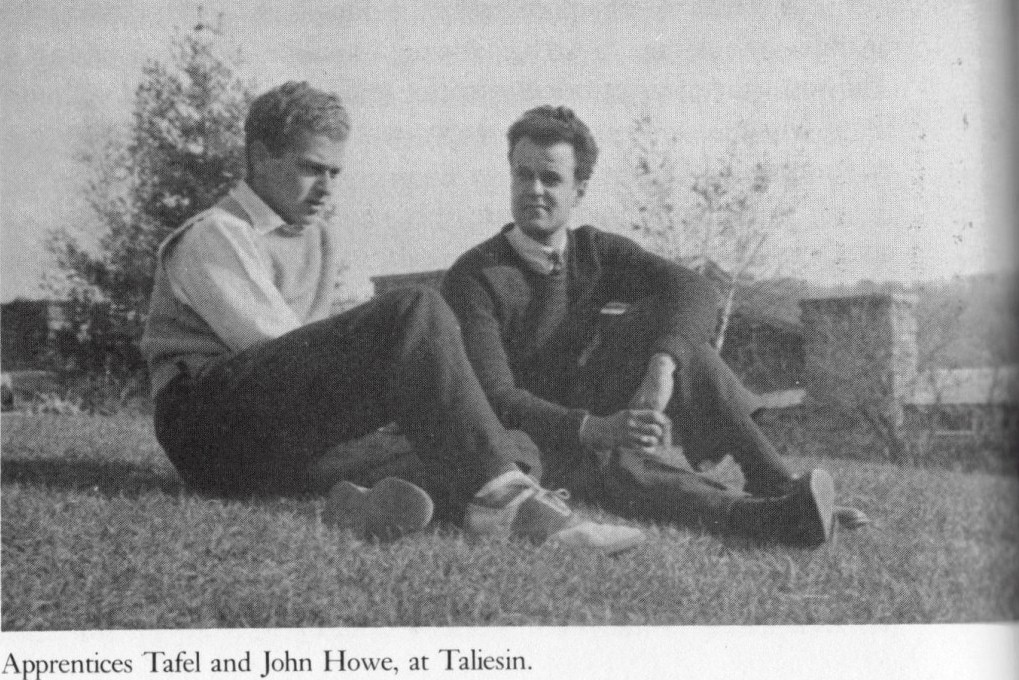

At Taliesin: Newspaper Columns by Frank Lloyd Wright and the Taliesin Fellowship, 1934-1937, compiled by Randolph Henning

Another companion to “Apprentice to Genius”.

The editor found as many of the weekly “At Taliesin” newspaper as he could. Then he typed them up and edited them into this book. The “At Taliesin” articles were written in the 1930s and show Wright and his apprentices as they lived them. The apprentices worked as entertainers, cooks, laborers, and farmhands. Also, imo, the book shows why these kids would move to rural Wisconsin to live and work with a man old enough to be their grandfather. And like it. The book contains photographs found almost nowhere else.

Here’s my blog post just about this book.

About Wright: An Album of Recollections by Those Who Knew Frank Lloyd Wright, Edgar Tafel, ed., with foreword by Tom Wolfe.

This book has written memories by a wide group of people from all aspects of Wright’s life: friends, co-workers, family, and former apprentices.

Books showcasing photographs and graphics:

A Way of Life: An Apprenticeship with Frank Lloyd Wright, by Lois Davidson Gottlieb.

Gottlieb apprenticed under Wright in 1948-49. She took the photographs of both Taliesins that are in this book. The colors in the photos are amazing and make you really appreciate Kodachrome film.

William Wesley Peters: The Evolution of a Creative Force. Editor emeritus John DeKoven Hill, with text by John C. Amarantides, David E. Dodge, et al.

“Wes” Peters’ “Box Projects” (bi-yearly projects given as presents by apprentices to Frank Lloyd Wright). The projects by Peters are beautifully illustrated, with an essay that explains them.

Websites:

Here are links to blogs written by former apprentices:

JG on Wright, John W. Geiger, Apprentice of Frank Lloyd Wright

John Geiger tried to trace apprentices and the years they started under Wright. So, this site includes the list he created. He also had photographs that he gave to the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.

An explanation of the site is here: https://jgonwright.net/jgdb1.html

Robert M. Green, an apprentice in the last months of Frank Lloyd Wright’s life, kept a website and wrote about his reasons for leaving the Taliesin Fellowship.

https://web.archive.org/web/20011120175318/http://robertgreen.com/robert_green/robert_green.asp

First published April 5, 2021.

I took image at the top of this page.