Looking west at the Taliesin residence in September 2005. I took this because I figured I should have at least one nice photo of Taliesin and the pond.

The pond at Taliesin that is.1

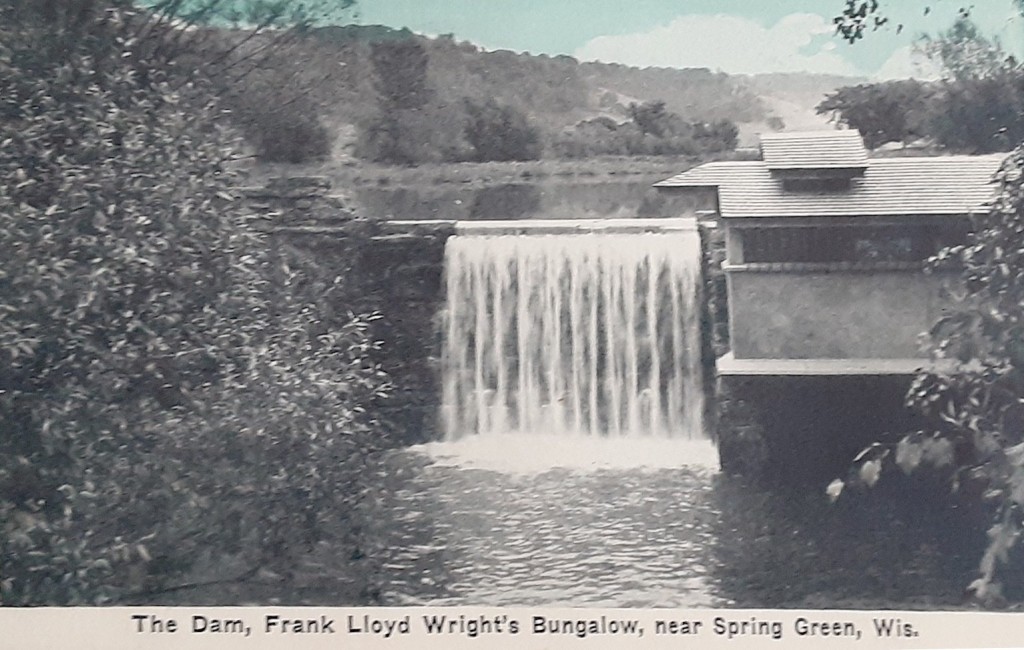

Wright created this pond by building a dam on the north side of the Lowery Creek in 1911-1912.

Here is a photo when the dam was being built. I showed it before in my post, “Did Taliesin have outhouses?“

Wright spoke about the dam after that disastrous “press conference” he gave on Christmas 1911 (that’s in “What’s the oldest part of Taliesin, Part I“). Here’s the part where the dam and pond are mentioned in the press:

There is to be a fountain in the courtyard, and flowers. To the south, on a sun bathed slope, there is to be a vineyard. At the foot of the steep slope in front there is a dam in process of construction that will back up several acres of water as a pond for wild fowl.

Chicago Daily Tribune, December 26, 1911, “Spend Christmas Making ‘Defense’ of ‘Spiritual Hegira.’”

The inlet for the pond, Lowery Creek, starts several miles south. Then it flows over the waterfall and into the Wisconsin River.

Find out more about the creek, and what’s done to protect this waterway at the Lowery Creek Watershed Initiative.

Except, at the moment, there is no waterfall, because there’s a creek but no pond.

In fact, the pond hasn’t been there since late 2019.

It will be back! But it had to be drawn down due to an inspection and repair work required by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

Check out the Facebook Live presentation

from the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation on the work from the summer of 2020.

It’s 26 minutes long. Staff from the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation talk about the project, why it was being done, and the particulars on what they’re doing. I think the original hope was to inspect the dam and do repairs for a completion by the end of 2021.

It’s 2023 and while things are looking up, the fact that the pond isn’t back reinforces the fact that

PRESERVATION IS HARD.

Unfortunately, we’re only reminded of that when things get, well… hard. I mean, you try to get things done carefully and in a timely matter, but there are times when things interrupt the best-laid plans.

However, in this case there’s also the fact that work at the pond bumped up against a worldwide pandemic,

Followed by disruption of supply chains

which you can see in a “This Old House” segment.

In case, you know, you’ve gratefully thrown experience about supply chain problems into the memory hole.

No, not THAT memory hole. I’m talking about the place where my memories of cold Wisconsin winters go every year.

Now, if you’ve been on a tour as of 2020, your guide maybe mentioned the pond, or the waterfall at the Taliesin dam.

But I don’t know. After all, one of the rules of tour guiding is

Don’t talk about what you cannot see

Therefore, I really should show photos then of what I’m talking about. That’s part of why you’re here, after all.

So, I need to bring back The Man when talking about the pond.

You know what man I mean.

While building Taliesin in 1911-1912 Wright decided to build the dam on the north end of the creek. He envisioned the pond as part of his long-range landscaping.

Here’s part of his writing:

A great curved stone-walled seat enclosed the space just beneath them and stone pavement stepped down to a spring or fountain that welled up into a pool at the center of the circle. Each court had its fountain and the winding stream below had a great dam. A thick stone wall was thrown across it, to make a pond at the very foot of the hill, and raise the water in the Valley to within sight from Taliesin. The water below the falls thus made, was sent, by hydraulic ram, up to a big stone reservoir built into the higher hill, just behind and above the hilltop garden, to come down again into the fountains and go on down to the vegetable gardens on the slopes below the house.

Frank Lloyd Wright. An Autobiography (Longmans, Green and Company, London, New York, Toronto, 1932), 173.

Wright’s writing conjures the image of a Japanese Woodblock print:

Ono Waterfall on the Kisokaidō (Kisokaidō Ono no bakufu), from the series “A Tour of Waterfalls in Various Provinces (Shokoku taki meguri)”

Artist: Katsushika Hokusai (Japanese, Tokyo (Edo) 1760–1849 Tokyo (Edo)). Date: ca. 1833

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City: Henry L. Phillips Collection, Bequest of Henry L. Phillips, 1939. Accession Number: JP2925. Public domain

Now, as for the pond, there’s my photo at the top of this post, and here’s a link to one taken in 1955 by photographer, Maynard Parker. The photo below is one I took from Wright’s bedroom terrace:

I took this in early May 2008.

And, since I’ve already written about the dam that’s there now, I should give you info on the dam that used to be there.

What?! There’s Another Damn Dam that we’ve got to know about?!

Well, don’t get mad at me.

And, YES!

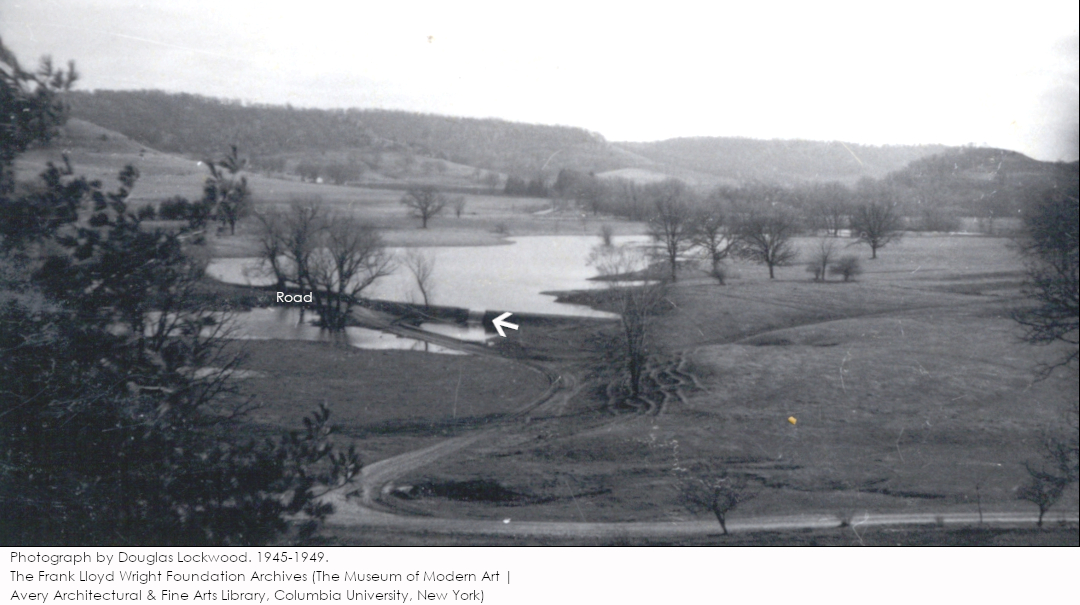

For several decades, the Taliesin estate had two dams. There was the lower dam, which still exists. But, in the late 1940s, he added an upper dam, south of the current one. This dam was smaller. I don’t know why Wright decided to add it. It was a pretty cool looking.

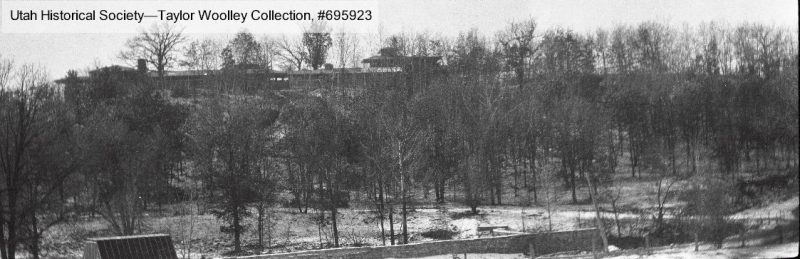

Here are two photos showing the upper dam. In the black and white one, you see it to the right of the entrance road:

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York), 2501.1246.

This photo was taken by Douglas Lockwood when he was an apprentice in the Taliesin Fellowship. You can see the road that I pointed out. This was also taken from Wright’s bedroom terrace.

You’d be standing near the spot of the photographer in my post, “History of Native Americans in the Valley“.

I put a closeup photo of the upper dam below.

Apprentice Mark Heyman took this in the 1950s. The flags you can see in the photo’s background make me think he took the photo while a summer party was taking place at Taliesin:

While the little dam was neat, it caused flooding upstream.

Understandably, that annoyed the neighbors.

In fact, neighbor Thomas King wrote in late October, 1945 letting those at Taliesin know that the dam wasn’t appreciated. He asked “if it was your intention” to live with neighbors that had over two feet of water in their cellar because of that dam.2

The upper dam was removed late 1960-early 1970s. Luckily for the neighbors, the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation cannot rebuild it.

As for the pond, it looks like it may come back in the year 2023. Because, while the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation repaired everything around the dam, you can’t tell what will happen. It’s looking good, but you don’t know.

Originally posted February 21, 2023.

I took the photograph at the top of this page in 2005.

Notes

1 I was told that Wright called it the Watergarden, but I couldn’t find the evidence to that while writing this post. He didn’t write “watergarden” in any document by him I transcribed. So, I didn’t find the term by searching for the word.

2 The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York). FICHEID: K066D06. Letter from Thomas King to William Wesley Peters, 10/25/1945.