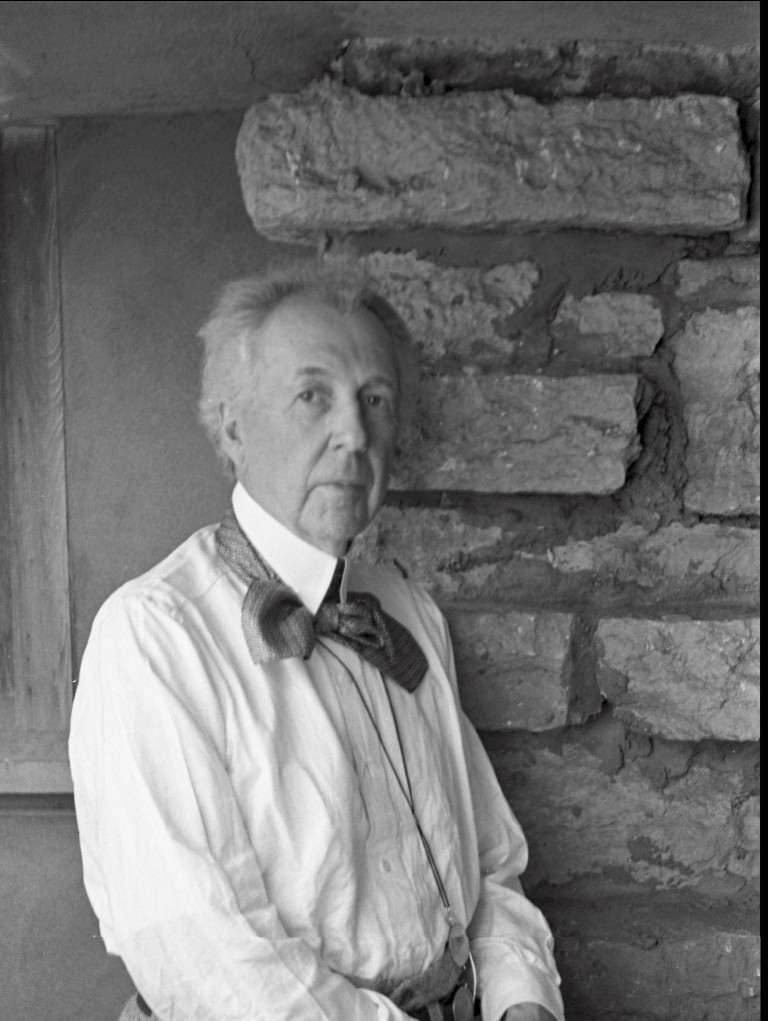

This post is about figuring out where Wright was standing in the photo at the top of this page.

And, several years ago, “Looked at some mortar,” was my answer to the question, “What did you do at work today?”

Wait – what? Why?

A collection of images in Delaware:

Earlier that day someone from the Hagley Museum and Library (Wilmington, Delaware) wrote me (as the historian for Taliesin Preservation) looking for a date on some images they have. It’s a collection of negatives by John Gordon Rideout.

According to the Hagley Museum,

John Gordon Rideout (1898-1951) was a noted industrial designer and architect based primarily in Ohio. The images in this digital collection come from an album of negatives in a collection of Rideout’s papers. Some of the images, likely dating to the early 1930s, depict Frank Lloyd Wright and his Spring Green, Wisconsin, estate, Taliesin.

There are 192 negatives from Rideout. Most of the images don’t show Taliesin, but I hope I had something to do with that date that’s on that page. 1933-34 is the date I gave for Rideout’s Taliesin images.

Figuring the date out from the other photos was easy. However, there was one photograph in the collection that I couldn’t immediately figure out. That photo is at the top of this page. That’s what led to me to look at mortar. In that photograph Wright stands against a stone wall with a ceiling over his head, and the frame of a window on the photograph’s left hand side. I figured I could find the wall where he was standing by looking for some of those mortar blobs. Turns out I was correct.1

Finding the site of the photo:

If I hadn’t seen the rest of the Rideout’s collection I might have thought Rideout had taken the image years earlier. That’s because Wright doesn’t look like the man we know: the fashionable, well-known man from the 1930s surrounded by his apprentices in the studios in Wisconsin or Arizona. The man in the photograph above looked like someone maybe 15 years before. I think it was his tie, billowy shirt, and the magnifying glass (like a monocle) that hangs around his neck.

Fortunately, according to Taliesin Fellowship member, Dr. Joseph Rorke:2

. . . [O]ne of the first things that Olgivanna did was to persuade Frank to abandon his flowing artist’s tie and shorten his hair, presumably because he was beginning to look faintly quaint and old-fashioned.

Meryl Secrest. Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1992), 428.

Regardless of when the photo was taken I had to figure out where Wright was standing. I knew he was at Taliesin (because of the stone, stucco, and wood) and despite what I thought, the photo comes from the early 1930s. So, I mentally walked through the structure to figure out his location.

Why didn’t I just know where he was?

Since Wright changed walls, doors, windows, etc., all the time at Taliesin, sometimes things in photographs no longer exist. And I don’t trust Taliesin’s drawings 100% of the time (he used the drawings to work things out; or he changed the designs as the construction proceeded). Based on what I know, I thought Wright was standing on a balcony off of his private office (the balcony no longer exists; he expanded the room).

So I drove to Taliesin to see if I was correct.1

Finding the mortar

I printed the photo and went to the room at Taliesin where I thought it was taken. Luckily two employees of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation were there working so I could ask them what they thought. The three of us went back and forth on it until we agreed to go over to the back of Wright’s vault.

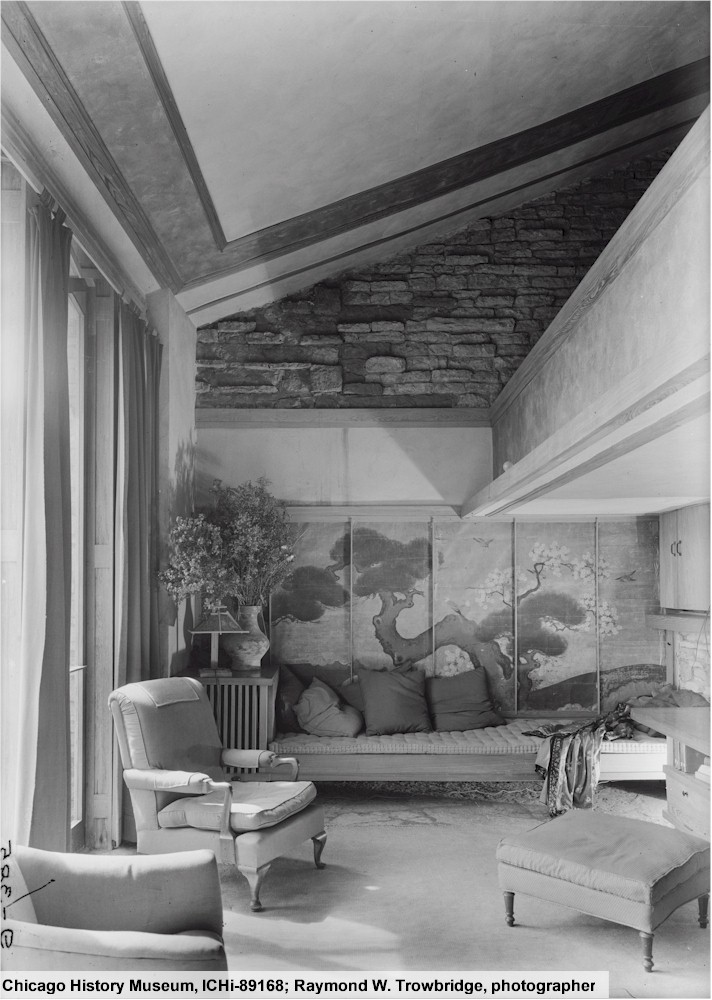

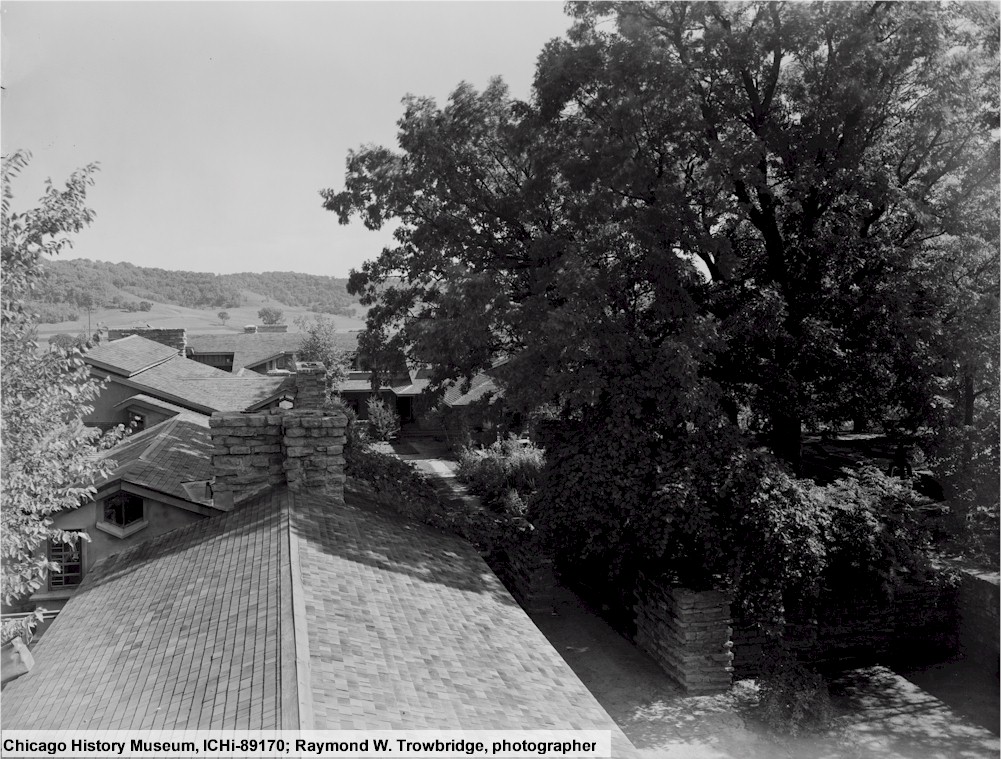

Here’s the area we looked at:

This was a photograph taken by me (thanks to Kyle for letting me inside the space to take photos).

Near the upper right portion of the photograph, under the horizontal pieces of stone, you can match the mortar to what’s in the photo with Wright. The stones are on the outside of his vault. In the photo with Wright, the top blotch of mortar is at around the same level as the top of his head.

So, there you go: the stone & mortar didn’t change. Just the stuff to the left of it did.

To the left of the stone you see into Taliesin’s drafting studio. The desk in the photo is where Wright would answer his mail in later years.

It’s not a working studio

Well, d’uh Keiran. I know it’s not a working studio. You do realize that Frank Lloyd Wright is dead, don’t you?

Yes I know that (about Wright’s relationship to life). But Wright stopped using this room as a drafting studio after 1939. In that year, another studio of his in Wisconsin was finished. That’s the 5,000 square foot drafting studio at Hillside on the Taliesin estate. So, it’s on the estate, but about half a mile away.

I talked about the studio in my post about Hillside. In fact, most of the photos you’ve seen where Wright is working in a studio in Wisconsin were taken at Hillside, not at Taliesin. You can also read this post at Wikipedia (the post that I, um, wrote), which is on Hillside and has an exterior photograph of that studio.

After the drafting was moved to Hillside, Wright used the Taliesin studio as his office.

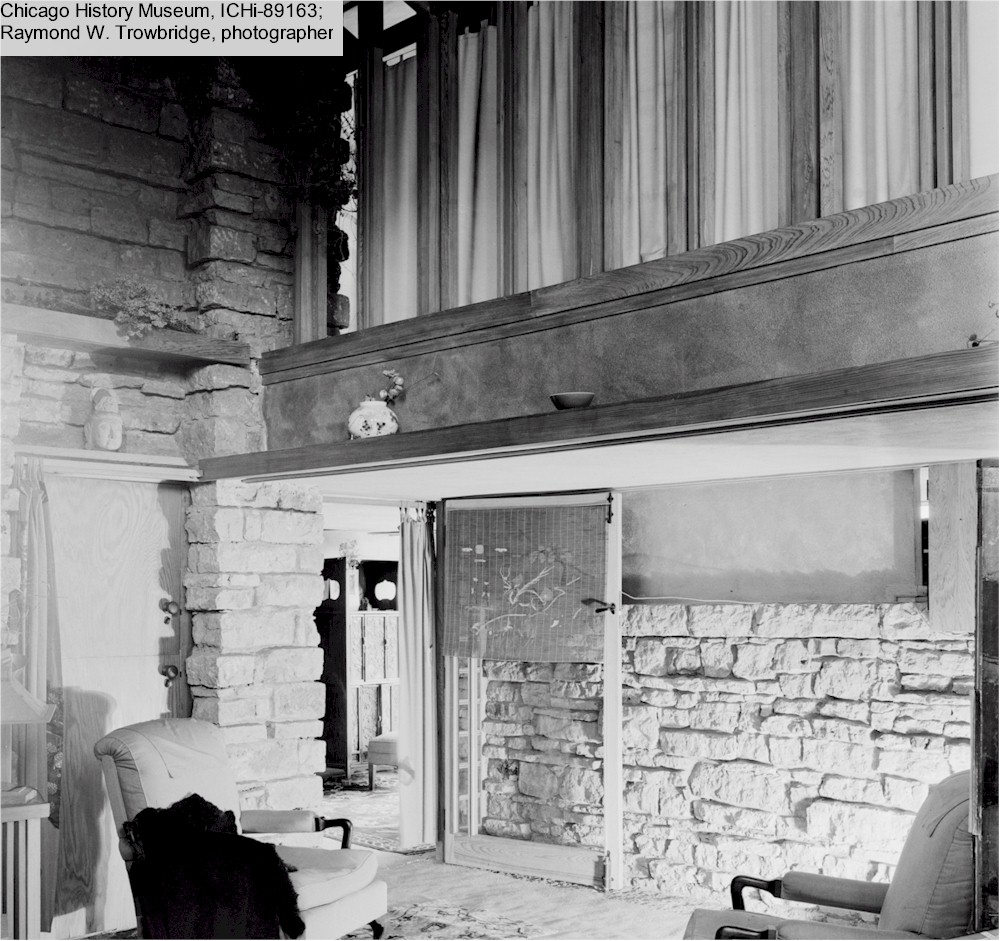

Photographs taken in Wright’s studio (later his office) back to what was just shown:

This was a photograph taken by me (thanks to Kyle for letting me inside the space to take photos).

Here’s Wright’s office desk from the other side. The stone on the left is his vault. I put in an arrow to show where I took the other photograph from. When Rideout took the photo of Wright, Wright was standing about where the arrow is pointing. Out through the windows there’s the beige-colored wall. That wall didn’t exist when Rideout took the photo of Wright. At that time, Wright’s private office was further to the left. The place where the beige wall is today was, at that time, an exterior balcony.

Originally published April 10, 2021.

The photograph of Frank Lloyd Wright at the top of this page was taken by John Gordon Rideout. Courtesy of the Hagley Museum & Library. The photograph is available from this URL: https://digital.hagley.org/2701_negalbum_strip22_004.

1 I tend to say “correct” instead of “right” when I’m talking/writing about things related to Taliesin because. . . Wright, y’know. I’ve noticed that others who work/ give tours at Wright buildings also say “correct” instead of “right”. It’s a way to keep one’s sanity. Because when you give tours of a Wright building, you’re already saying his name and also saying, “And to your right. . . . “

2 Taliesin Fellowship, 1957-2013. “Dr. Joe” was 95 when he passed away.

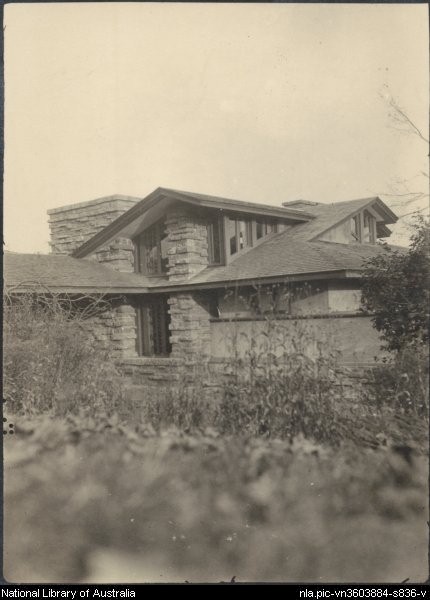

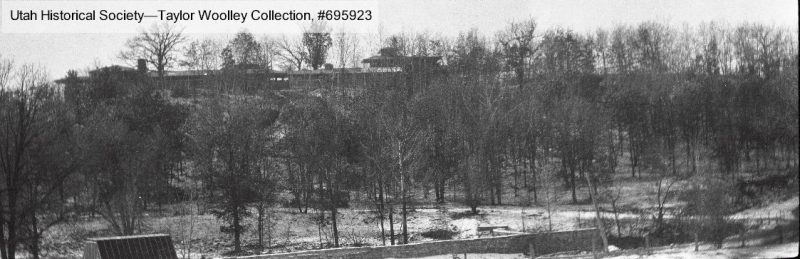

You walk up the steps at Taliesin to Wright’s studio at Taliesin (the north wall of the studio is to the right). The parapet from the Taliesin I photo ended at the stone that is to the left of the tree trunk (the tree trunk is to the left of the window that’s on the extreme right in the photograph) .

You walk up the steps at Taliesin to Wright’s studio at Taliesin (the north wall of the studio is to the right). The parapet from the Taliesin I photo ended at the stone that is to the left of the tree trunk (the tree trunk is to the left of the window that’s on the extreme right in the photograph) .