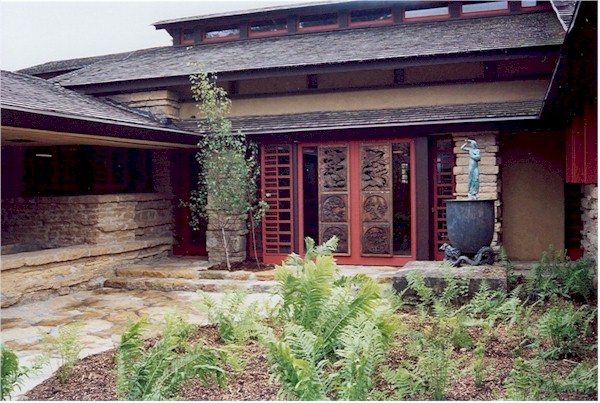

Taliesin’s Garden Court photo taken in August, 2002 by Doug Hadley, then the Landscape Coordinator.

In this post I’m going to write about when a stone wall was built at Taliesin’s Garden Court, changing it from an entryway into a private courtyard.

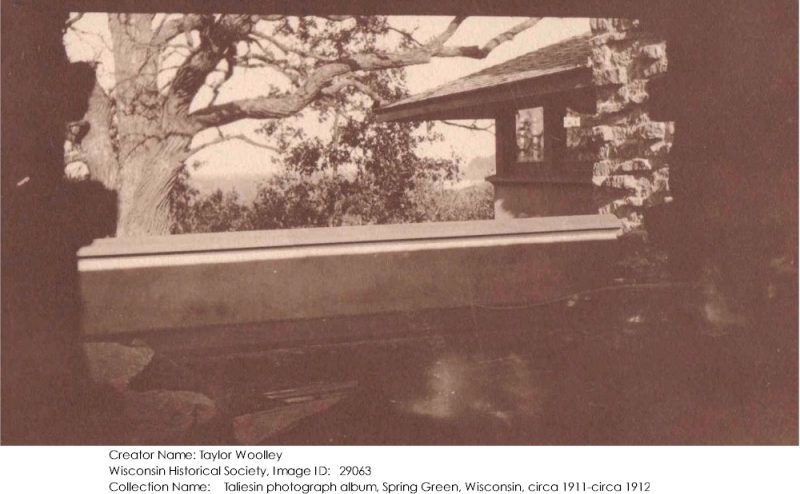

The Garden Court used to be the courtyard where people stopped when they arrived. I showed a couple of old photographs of that courtyard in my post, “When Did Taliesin Get Its Front Door?” The courtyard was the forecourt from the time that Taliesin was built in 1911, until after its second fire in 1925.

After that, Wright made it into the Garden Court.

Ok – got it. But why do you have to use capital letters in front of the words Garden and Court, like a snooty know-it-all?

I think it’s because Garden Court is its proper name. I didn’t name it that. Plus, when you’re at Taliesin (or talking about it), you say those words and everyone knows what space you’re talking about.

Like, when I went to Taliesin West (Wright’s home in Arizona) people said “Kiva“, “Cabaret” and “Pavilion“, while talking about those spaces. I didn’t really know what they were talking about, but tried to not look as confused as I felt. I knew they’d tell me on tour, so hopefully I’d learn. Although, I still have to check with myself on The Cabaret vs. The Pavilion.

Besides: it’s not “snooty know-it-all”. . . it’s “socially awkward…” I don’t think I’m snooty, anyway.

Besides,

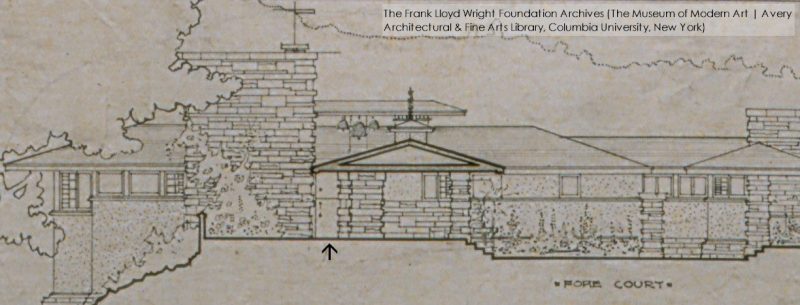

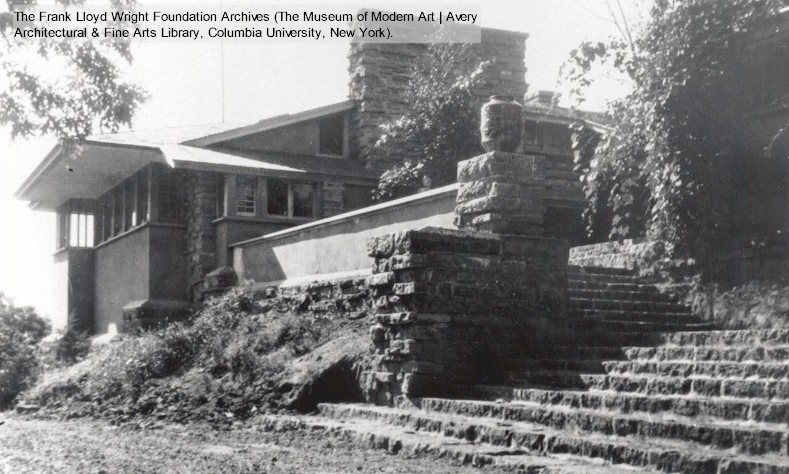

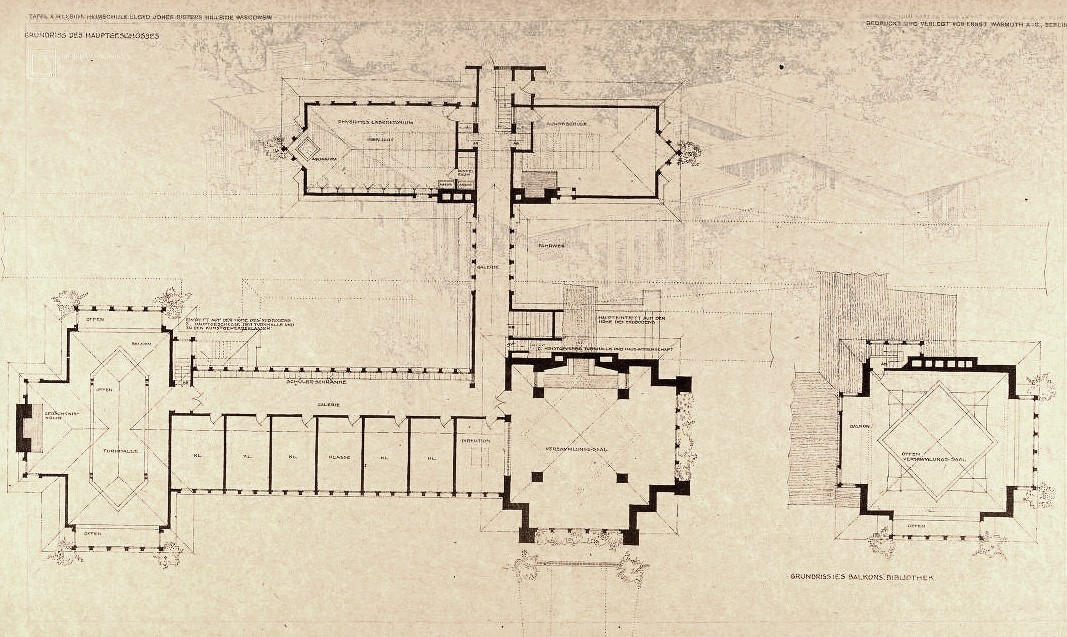

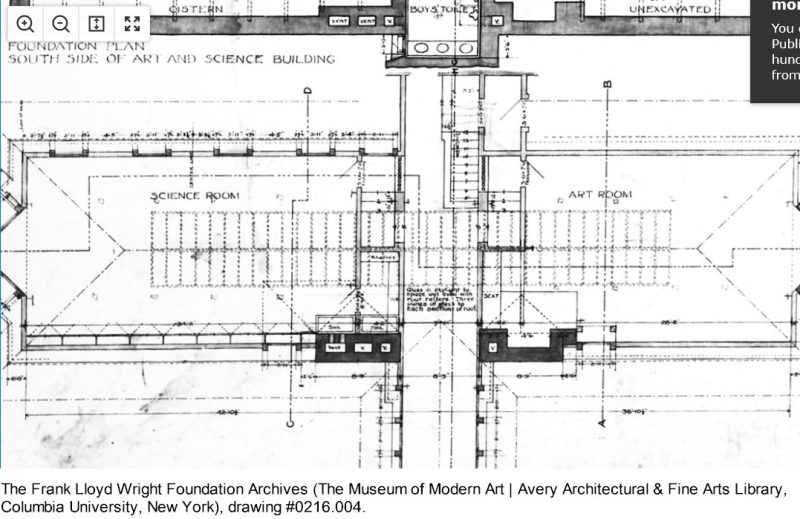

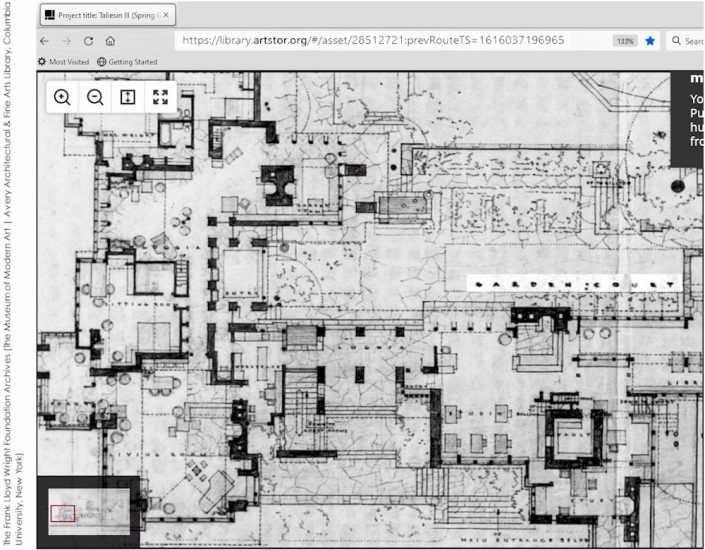

Wright labelled the court in the drawing published in the book, In the Nature of Materials. And also in one other Taliesin drawing, below:

If you click the link, you’ll see the whole drawing is larger. I made the label “Garden Court” a little bigger, and lighter.

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York).

Back to the Garden Court

Like I said, Wright created it after Taliesin’s two fires. It might be because Wright didn’t like people driving right up to the living quarters.

This was even though he might have had reason for optimism about his career in 1925.

This is despite the 1925 fire that had destroyed so many of his art objects. And, oh yeah: his damned home. Again.

But there were probably some positive signs floating around. After all, he had done some interesting work in California, and was well known because of his Imperial Hotel. That building was one of the few that stood in Tokyo after Japan’s devastating Great Kanto earthquake two years before.

And, finally, on the personal side, Miriam Noel (his second, unstable, wife) had left him (the year before), and he was newly in love with Olgivanna (with whom he spent the rest of his life).

Regardless, he no longer wanted people driving right to the forecourt when they came to Taliesin. So, he added a few things to redirect people on their way up.

As a result, he blocked the old drive in two ways:

From the south:

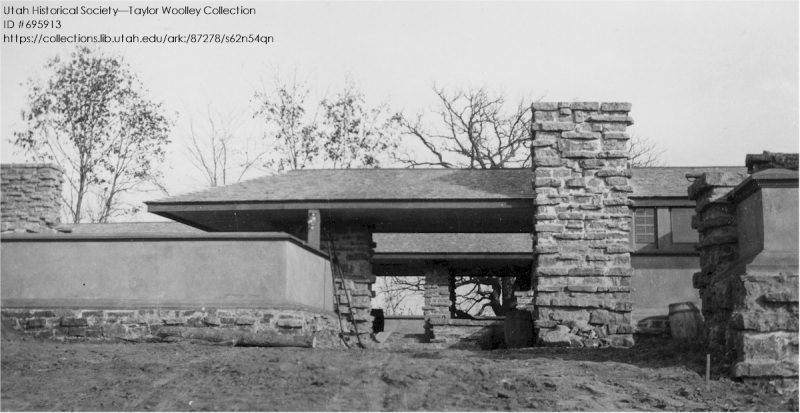

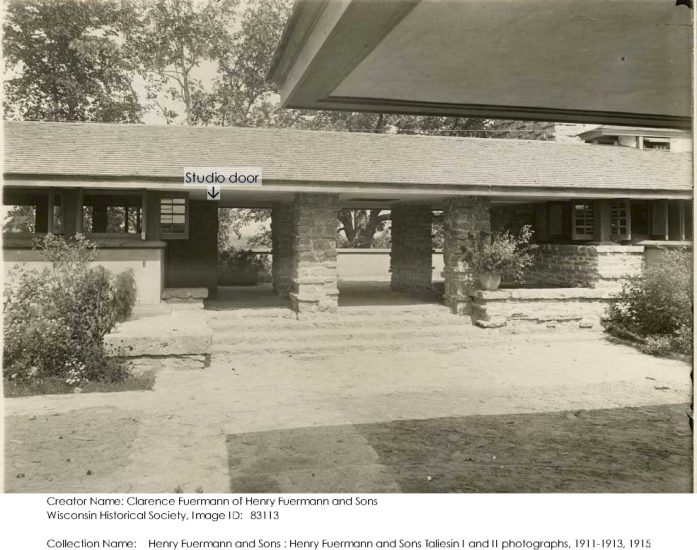

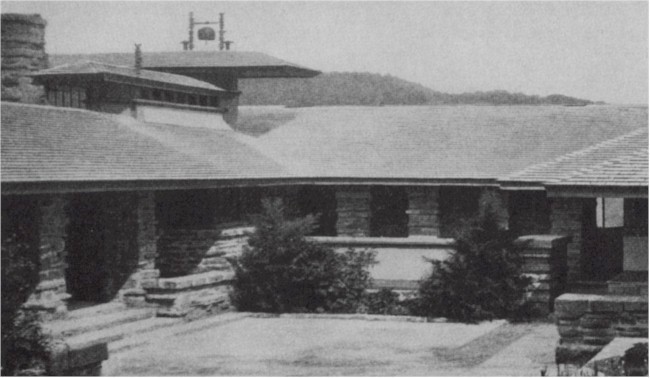

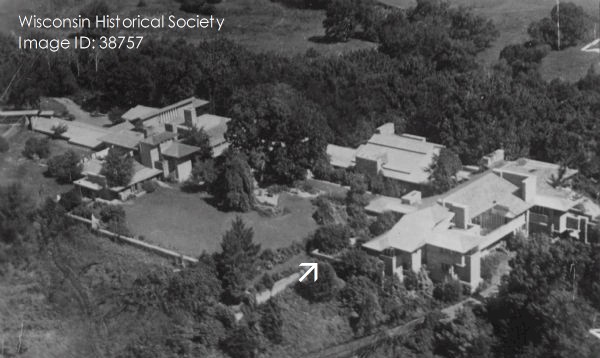

He built a stone court that ended with a parapet. You see the wall at the end of the terrace in this 1932-33 photo from the Wisconsin Historical Society:

Wisconsin Historical Society, image ID: 38757

The arrow in the photo points to where the carriages used to drive when there was a road that continued way.

From the west:

This west here is the part of the building on the left in the photo; under “Image ID: 38757”.

It might have been easier to drive up that way because you didn’t even have to drive up a hill, to get right outside of his studio. So, men and women could be working in the studio, then look up and see people they didn’t know right outside of of the windows. Or those people might walk into the room.

In order for them to drive from the west to the studio

They would have driven through a couple of gates, then under the old hayloft and past the former horse stables.

I suppose it wouldn’t have been bad if Wright were waiting for a client. Plus, there was a door under the hayloft to keep random people (and cows) out. But if the draftsmen forgot to close the door, and people came in, it could really interrupt you.

Like, for a couple of years, when I worked more in the tour department at Taliesin Preservation. On the first floor of the visitor center, there’s a door that goes out to a loading dock. That’s because one summer, at least two groups of people walked in, thinking the door was the building’s entrance.1 We had to tape a little sign on the door telling them “This is not an entrance”. Seemed to work well.

You can imagine other draftsmen or -women, working on a nice drawing in Wright’s studio, when a stranger comes walking in to the room, wanting to know if this was the “Crazy House” (like I mentioned in my post, “This Stuff Is Fun For Me“).

btw, at that time, they didn’t ask if Taliesin was the House on the Rock. Because that didn’t exist yet.

So, the wall might have been an effort to make a journey to the studio more onerous. The wall isolated the former Forecourt, and allowed an expansion of the gardens.

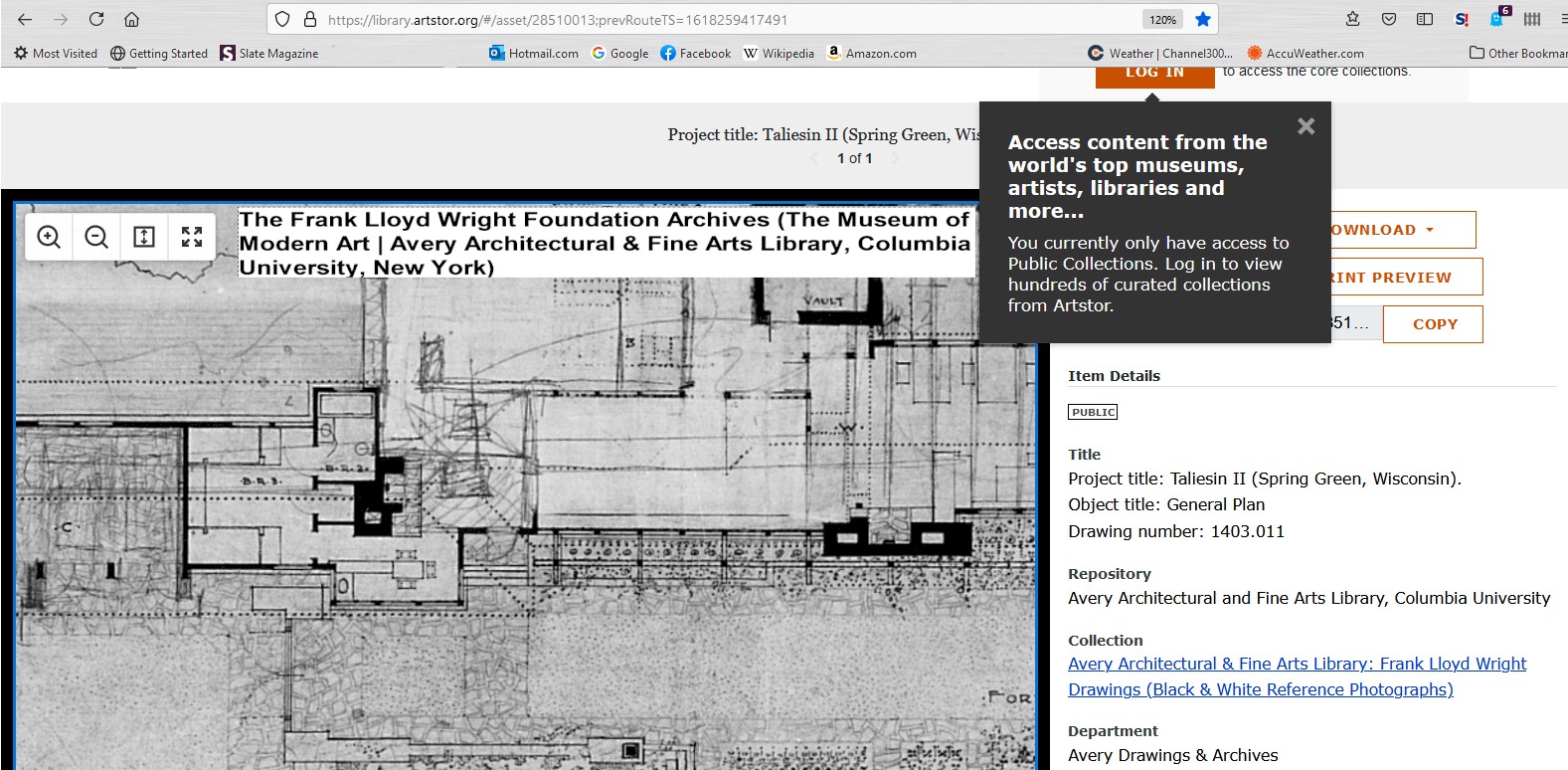

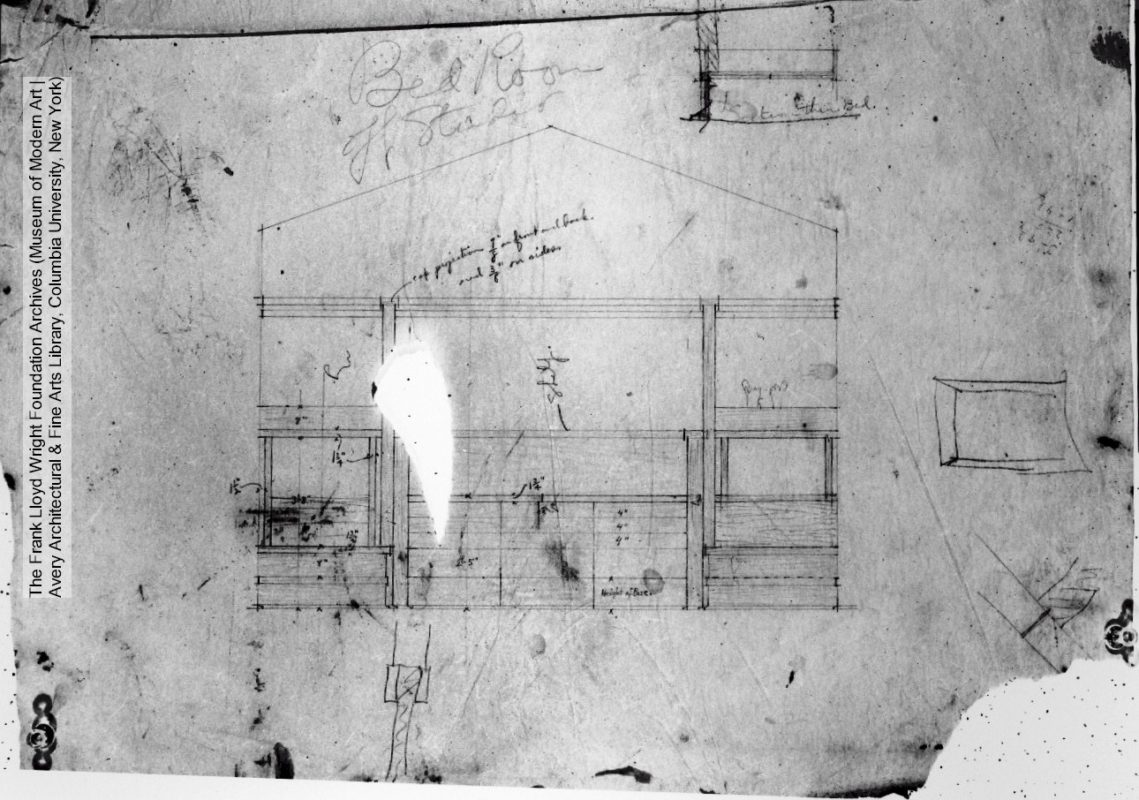

He took one of his drawings to figure out his plan

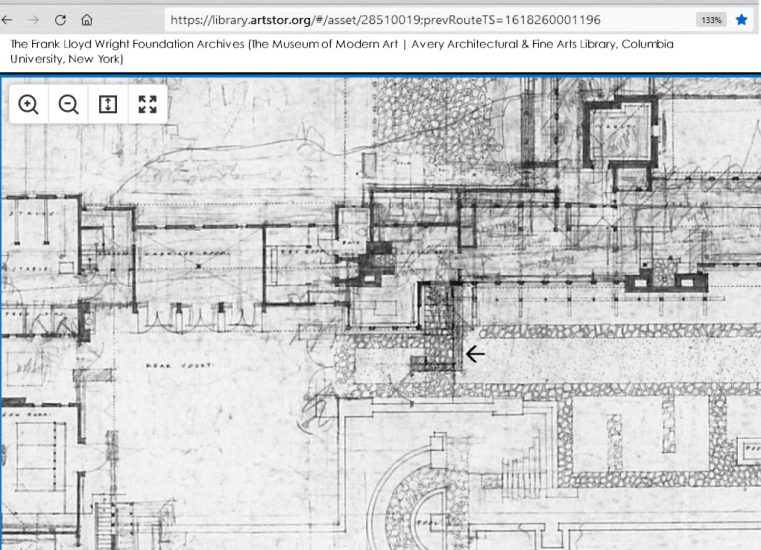

Here’s a Taliesin II drawing where he made changes in pencil. An arrow is pointing at the wall below –

The drawing above links to the version online. If you click on it, you’ll see that the actual drawing is a lot bigger.

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

One of the changes Wright wanted was to make the old CARRIAGE HOUSE into bedrooms. So, he took a pencil and drew in bay windows at the Carriage House.

One of those rooms with bay windows is where George Kastner lived when he started working for Wright. You saw two photographs inside Kastner’s room in my last post, “Oh My Frank, I Was Wrong!“

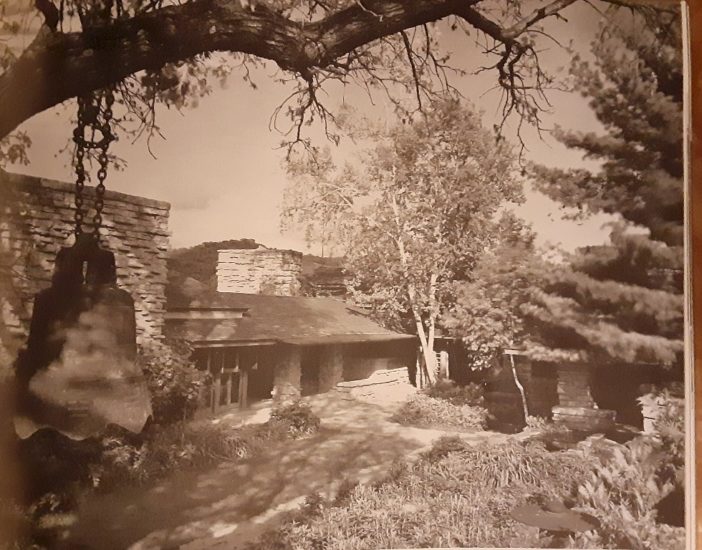

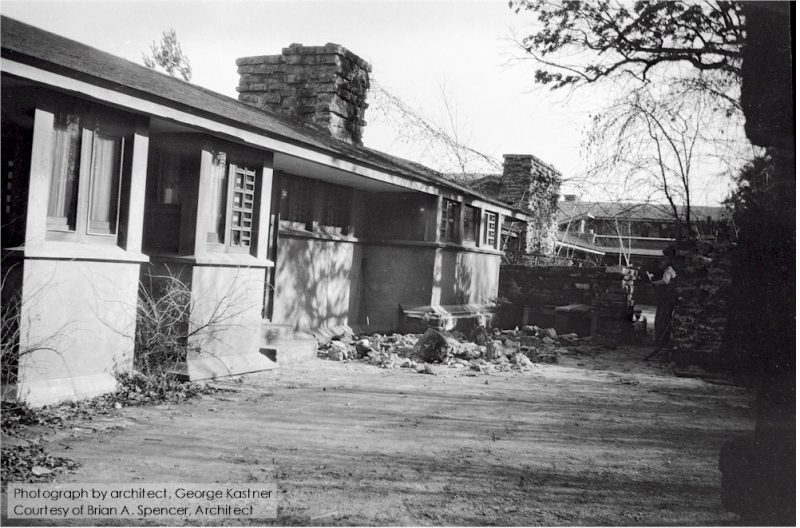

Kastner also took a photo outside of his room. At that time, November or December, 1928, he was living at Taliesin. The photograph shows the Garden Court wall being built:

Courtesy of Brian A. Spencer, Architect

Taken in the Middle Court, looking (plan) northeast. The new bay windows are on the left, with the Taliesin III living quarters in the distance on the right. The chimney for the studio fireplace is the second chimney on the right.

The chimney on the left eventually became the fireplace for the living room used by Wes Peters, and his wife, Svetlana Hinzenberg Peters.

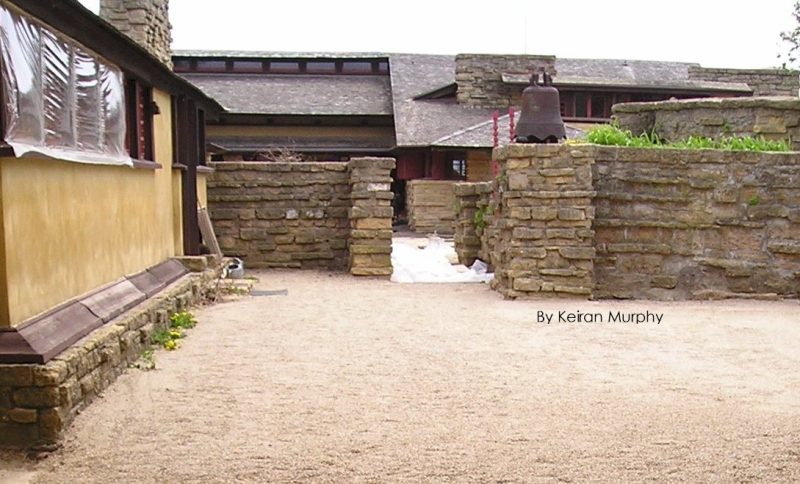

A photograph I took in this area is below. The stone wall is slightly taller than it was in Kastner’s photo. Stonemasons later heightened the wall by a stone course or two, probably in the year after Kastner took his photograph.

I took this photograph in April 2004.

First published, May 20, 2022

The photograph at the top of this post was taken by former Landscape Management Coordinator, Doug Hadley.

Note:

- My theory on why people would walk in the door was is that the grounds people had cut down the yew bushes, so people saw the door more easily when driving by the building. But putting up the sign on the door stopped people from walking in unexpectedly.