This is a photograph of the cover of “The Album”. The image was sent to me by the person selling it through the online auction site, Ebay, in January 2005.

Since we’re in January, I’ll take the time to expand my story of “The Album” that I mentioned months ago in my entry, “Post-it Notes on Taliesin Drawings“.

The Album was how I knew that Wright had designed bunkbeds for his draftsmen. Two photographs in The Album showed the bunkbeds and later, I found a drawing of them in Wright’s archives. I marked it with a post-it note.

“WHAT?! You’re putting Post-It notes on archival drawings?!”

Calm down and read the post to get the story.

Finding out about The Album:

In January 2005, Carol Johnson (Taliesin Preservation’s then-Executive Director), met me after I’d just gotten out of my car for work and said,

“Tony told me there are photos of Taliesin on Ebay.”

“Tony” was Tony Puttnam (1934-2017), who became Wright’s apprentice in 1953.

The director knew they were really old and rare and sent me the website address for the Ebay auction so I could try to see them. Once I looked online, I recognized 2 of the 3 photographs shown by the seller.

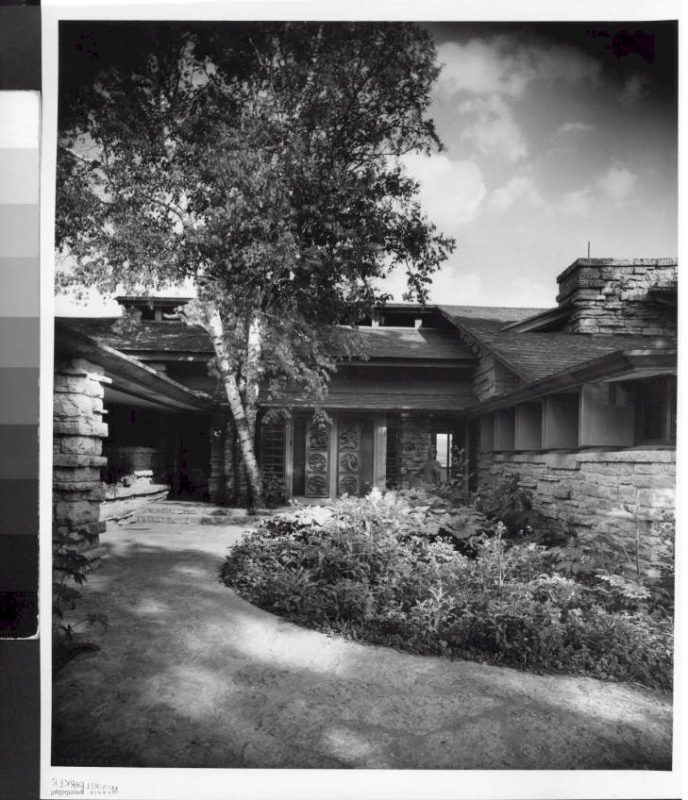

Yes: these were really rare images in a handmade album (the cover of which is at the top of this page). Building details dated them to 1911-12.

I wrote to the seller, Helen Conwell, as someone who “might” buy them. I asked her to send me some of them.

Sounds sneaky, but I didn’t say anything fraudulent. My supervisor and I thought we might be able to get money for them, depending on what they were. We had dreams, you see.

Conwell sent me 28 scans (out of 33 images). I had seen 10 of them before this.

Where had I seen them?

See, in the early 1990s, when the Taliesin Preservation Commission—as the Taliesin Preservation was known then—began the restoration of Taliesin, others tried to get this new organization up to speed. Architects, architectural historians,1 former Wright apprentices, and those in Wright’s archives at the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation gave “TPC” copies of photographs to enhance the knowledge of Taliesin’s history.

In particular, the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation gave copies of Taliesin I photographs from the “Clifford Evans collection” at the University of Utah.

Why Clifford Evans?

Here’s a rundown on Evans (1889-1973), an architect who donated his materials to the U of UT:

- Evans was the architectural partner of a man named Taylor Woolley.

- Taylor Woolley was a draftsman for Frank Lloyd Wright in Oak Park, Italy, and Taliesin.

- Taylor Woolley gave some of his items to the Clifford Evans collection. Included were his photos taken during the first year of Taliesin, some of which are also in The Album.

I’ve already posted Woolley’s photographs on this blog. Here are some entries including them

- The Woolley photos in Utah include 9 that The Album didn’t have.

I told people what I knew

The week The Album was up for auction and the whole Wright world was freaking (which I wrote in “Post-it Notes…”), I told people a version of what I just wrote above. It really didn’t do anything, but I felt the story had to get out there. Besides, I wasn’t the only person who knew these images were repeated elsewhere. There were those at Frank Lloyd Wright’s Archives; and a professor in Utah, named Peter Goss.2

Why were these important?

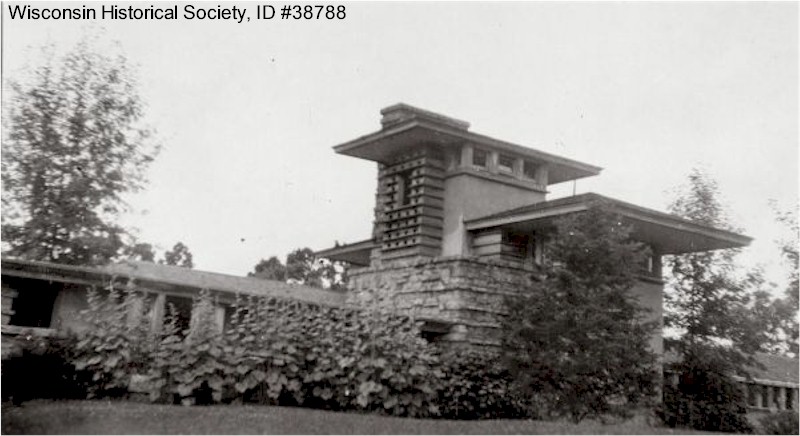

Previous to this album’s discovery, most Frankophiles knew the existence of about 60 photos of Taliesin I (1911-14). This album had 33 more images, 32 of which had never been published.

One had been published in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin and Taliesin West, by Wright scholar, Kathryn Smith.

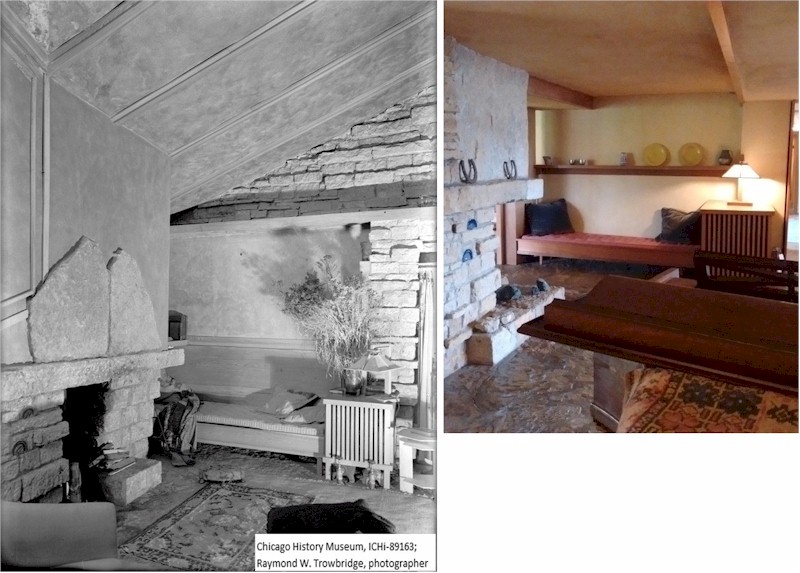

Photos from The Album included several of Taliesin’s east façade, its carriage path in its first autumn, and almost 10 interiors, including Wright’s Drafting Studio.

One in the studio has workmen in front of its fireplace. The Wisconsin Historical Society says that they’re “maybe at Taliesin”. No: they’re actually at Taliesin. Trust me.

Nancy Horan wrote in her novel, Loving Frank, that these men were in the Living Room, but that’s wrong: the photo shows them in the Drafting Studio. I don’t blame her that she didn’t realize this was at the Drafting Studio fireplace. It took us a while to figure it out, too.

Note: when I write “us”, I usually mean “me”.

That’s not even mentioning the two photos with the bunkbeds.

Moreover,

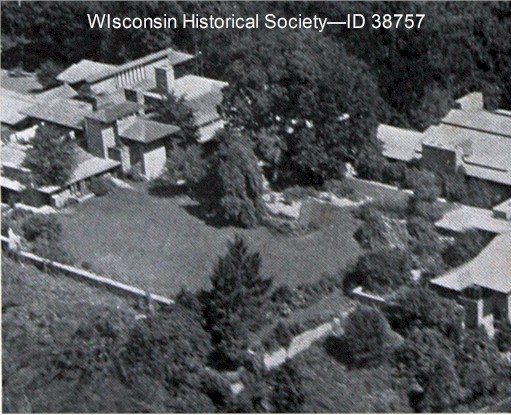

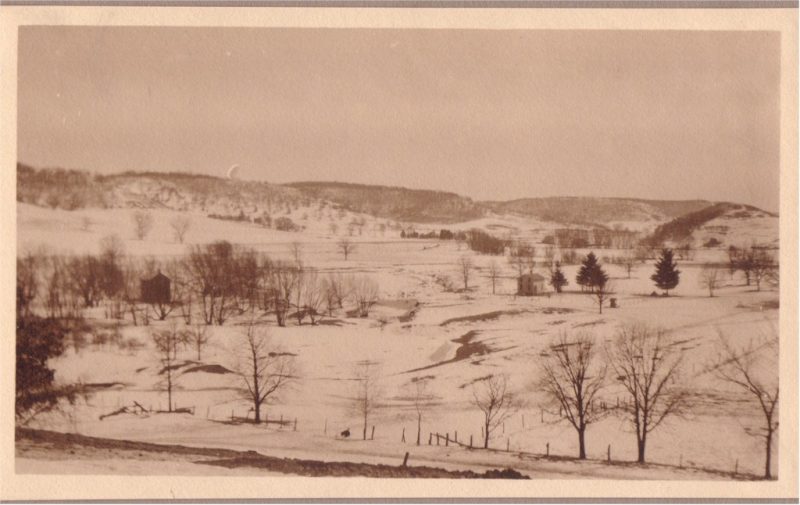

The Album shows landscape photos all over what is now the Taliesin estate. There’s one of them, below:

I went out later, trying to match the views. My attempt to do that is in color, below:

I took this photograph in March of 2005. In both photos, Taliesin is stands behind and to the left of the person taking the photograph.

But, more importantly,

This album, showing the newly completed building, had a history that could be traced. In other words, it had a “provenance“. Someone from the Spring Green, Wisconsin area owned the album, then sold it to Conwell in the 1970s.

End of the auction:

Helen Conwell thought she would get about $200 for an album that sold for $22,100.

I wrote about it in “Post-it Notes…”, but you can also read here how Conwell got the album and how the Wisconsin Historical Society acquired it.

While the photographer was unknown in 2005, I knew it was likely Taylor Woolley. Author Ron McCrea proved this in 2010 when he found Woolley’s collection at the Utah State Historical Society. I wrote about him in my post, “This Will Be a Nice Addition“.

So, that week was exciting.

And you can see all of the images online at the Wisconsin Historical Society website, here.

That said,

It’s been much too long since a big, unknown haul of Taliesin photographs has come to light. Seriously: we need new, old photos of Taliesin.

Now, there are photographs taken in the early 1940s by David or Priscilla Henken that were published in A Taliesin Diary: A Year With Frank Lloyd Wright.

But that was published almost a decade ago. Yet, I still have hopes that children of those who were in the Taliesin Fellowship in the 1950s will discover photographs their moms or dads took while apprentices at Taliesin.

What do I want to see?

Off the top of my head, I’d like detailed photographs of Olgivanna Lloyd Wright‘s bedroom taken in 1957-58. That’s a pipe dream, but what you see in her bedroom today was restored and worked on with as much information as possible. But it’s probably not the room as it stood. We do what we can.

“If we knew what we were doing, we wouldn’t call it research, would we?”

A quote often ascribed to Albert Einstein that he apparently never said/wrote. Read someone writing on how it doesn’t appear to have come from Einstein.

First published, January 20, 2022.

The scans of The Album’s cover, and the exterior photograph taken in the winter were sent to me by Conwell in 2005.

They are the property of the Wisconsin Historical Society, and can be found here and here.

Notes:

1. Like Sidney K. Robinson, who owns the Ford House by architect, Bruce Goff.

2. Goss wrote about Woolley in the article, “Taylor A. Woolley, Utah Architect and Draftsman to Frank Lloyd Wright,” Utah Historical Quarterly (2013) 81 (2): 149–158.

https://doi.org/10.2307/45063406